Rails-to-Trails programs at a crossroads

A recent Supreme Court of the United States decision may stall Rails-to-Trails programs in some states.

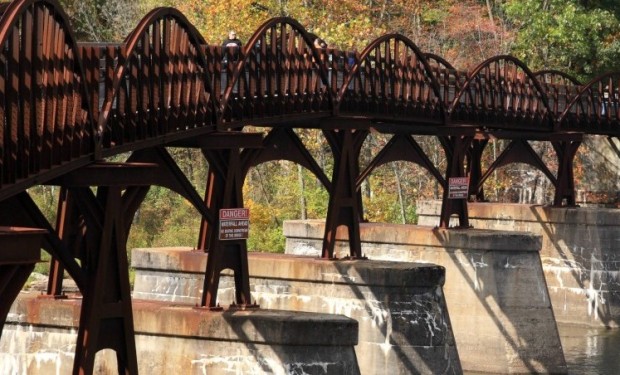

The Rail-Trails program in North Carolina and Rails-to-Trails programs across the country have been widely celebrated methods of environmental conservation and railroad corridor preservation. These trails, such as the Virginia Creeper and the local favorite, the American Tobacco Trail, follow the old, often abandoned or neglected rail beds laid by railroad companies. Before the Supreme Court of the United States’ decision in Marvin M. Brandt Revocable Trust v. United States (pdf), if the federal government wanted to convert old railroad lines into trails, it could do so fairly easily – the supposed easement granted to the railroad was thought to revert back to the Government once it was abandoned, allowing for further trail development.

In an 8-1 decision, the Court remanded Brandt back to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit and held that these abandoned easements do not necessarily revert back to the Government. Instead, the encumbered property is held by private landowners, denying the Government the right to maintain the railroad easement and therefore build trail systems where the railroads once existed. While legally this decision makes sense, it may have a negative effect on Rails-to-Trails programs, particularly in western states, because of the way land was deeded from the federal government to private landowners.

Ultimately, this decision will prevent the U.S. Forest Service from turning the railroad right of way into a bicycle trail and could empower other private landowners to challenge governmental reclamation of land for trail development.

During the height of westward expansion in the nineteenth century, Congress passed the General Railroad Right of Way Law of 1875, which established a “uniform approach” to railroad development. This law granted rights of way easements to railroad companies and required homesteaders, who became private landowners through deeds issued by the federal government, to give the companies access to their property. The problem, however, was that the right of way law did not state what would happen to the land encumbered by the easement once the easement was abandoned.

In 1976, the United States “patented” an eighty-three acre parcel of land in Fox Park, Wyoming, to Melvin Brandt and his wife, conveying fee simple title with an exception and reservation for various road rights of way. If those rights of way were to ever cease to be used by the United States for a period of five years, the easement would terminate; however, when discussing the railroad easement in question, the patent did not specify what would occur if the easement was abandoned.

The railroad easement was used in various capacities until 1996, when the Wyoming and Colorado Railroad declared its intent to abandon the right of way – the appropriate method of properly abandoning the railroad’s rights. The abandonment was completed in 2004. In response, the United States initiated an action for a judicial declaration of abandonment and a quiet title action for the property at issue. All of the landowners that had property crossed by the old right of way settled with the Government except for the Brandts, who argued (pdf) that because the right of way was just an easement, the railroad’s declared abandonment meant that the Brandts now “enjoyed full title to the land” once the easement was gone. In opposition, the Government argued that it retained a reversionary interest in the right of way, which would be restored upon the railroad’s declaration.

After the Court determined that an easement was in fact what Congress conveyed to the railroad, the Court agreed with the Brandts that they enjoyed full title to the land and that the Government did not retain any interest in the property. Ultimately, this decision will prevent the U.S. Forest Service from turning the railroad right of way in Fox Park into a bicycle trail and could empower other private landowners to challenge governmental reclamation of land for trail development.

Because only sections of trails are usually rail banked, determining whether an entire trail is affected could be a potentially confusing and contentious process.

While many fear that Rails-to-Trails programs will suffer due to the Brandt decision, the case’s real impact will be state and case-specific, depending on how property was granted. In many instances, each rail-trail conveyance will have to be examined in order to determine its ownership. According to Kevin Mills, Rails to Trails Conservancy’s Senior Vice President of Policy and Trail Development, the majority of affected trails will be west of the Mississippi River. For the most part, however, current and planned trails will not be impacted. Mills cites six different factors to consider when determining whether a particular rail-trail will be affected by the decision, including whether the rail corridor was originally acquired by the railroad through a federally granted right of way, whether the trail manager owns full title to the corridor, whether the railroad corridor falls within the thirteen original colonies, and if the rail corridor was “rail banked.”

Rail banking has been a very effective way of securing land for rail-trail development, allowing the abandoned rail lines to be converted into trails with a condition that the railroad bed can “return to railroad use” if a need arises in the future. The rail banking process requires that trail developers negotiate with the railroad after the railroad notifies the federal Surface Transportation Board (STB) of its intention to abandon the line.

Because only sections of trails are usually rail banked, determining whether an entire trail is affected could be a potentially confusing and contentious process. For example, the John Wayne Trail, which runs through Kittitas County, Washington, could be at risk because some trail portions are not rail banked. On the other hand, the Naches Trail and the Klickitat Trail, which run through the same county, will most likely not be affected due to its rail banked status.

“People are getting the idea that you can fight city hall and win. You can even fight Washington, D.C., and win.”

Despite the potential harm to Rails-to-Trails programs, many private property owners are celebrating the Brandt decision. The ruling could affect around eighty other cases involving over 8,000 claimants and is a victory for individual property ownership. Steve Klein, staff attorney for the Wyoming Liberty Group, a policy-based research organization, stated that Mr. Brandt’s holdout on surrendering his property rights would inspire like-minded and similarly situated property owners facing government pressure: “[p]eople are getting the idea that you can fight city hall and win. You can even fight Washington, D.C., and win.” For groups like the CATO Institute (pdf), which filed an amicus brief in the case supporting Brandt, and the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), the decision will also finally ensure that landowners will receive just compensation for their property, “affirming the principle that the government cannot redefine previously recognized property rights out of existence.”

The current method of land acquisition seems to have saved North Carolina’s Rail-Trails program and future development.

Luckily for North Carolina’s trail enthusiasts, the Brandt decision’s impact will be limited. One of the main reasons North Carolina trails will not be as affected is because of the difference in North Carolina railroads and railroads in western states. In the West, railroads often existed before settlement. Railroad companies were granted long expanses of property in “checkerboard blocks”(pdf) from the federal government, adding to the overall length of railroad lines and later to the extensive rail-trails in the region. In North Carolina, however, railroad companies were forced to build their lines around already settled private grantors, giving these private landowners a future interest in the encumbered land.

In North Carolina, if a railroad corridor is declared abandoned through the proper STB procedures, adjacent property owners can claim a portion of the former corridor property, depending on how the railroad obtained the land in the first place. This reclamation requires developers like N.C. Rail-Trails to visit each property owner individually to obtain an interest. While N.C. Rail-Trails is pushing for a new state policy to make reuse of former railroad corridors more attainable for trail expansion, the current method of land acquisition seems to have saved North Carolina’s Rail-Trails program and future development.

The thirty rail-trail projects in North Carolina, covering over 130 miles, have been critical in community growth, environmental conservation, and increased tourism. Perhaps the greatest benefit these trails create, however, is an avid interest in the outdoors and an appreciation of the great history of transportation these corridors leave behind.