Former student protected after bashing Cooley Law School

The Michigan Court of Appeals considered First Amendment rights and ruled in favor of a former law student by issuing a protective order for anonymous speech.

In 2011, a former student and internet blogger posted defamatory statements about Thomas M. Cooley Law School, including that the school’s self-proclaimed ranking as the second best law school in America is “as ludicrous as asserting that I am the second smartest man in America.” As a result of the allegedly slanderous posts, Cooley filed a complaint against the anonymous author, Doe 1, claiming that the accusations were defamatory in nature. The initial issue revolved around the revelation of the blogger’s identity. Even though Doe 1 moved to quash the disclosure of his identity, the blog host, Weebly Inc., later disclosed this information. Cooley subsequently filed a new complaint that specifically named the blogger.

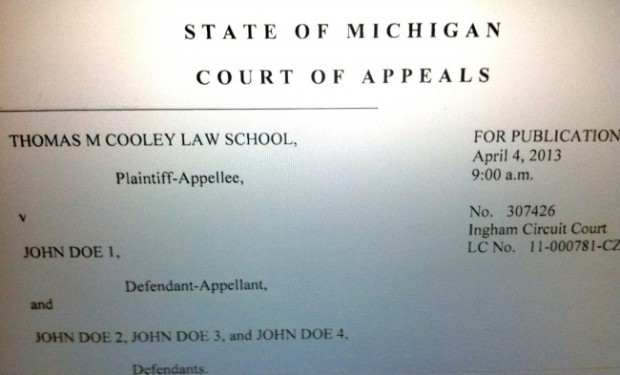

Cooley’s lawsuit against its former student is one that brings up important issues for future cases. The Michigan Court of Appeals recently ruled (pdf) on Doe 1’s appeal of the trial court’s denial of his motion to squash a subpoena seeking his identity. The Court’s decision first addresses whether anonymous speakers’ First Amendment rights must be considered in issuing protective orders that ensure their secrecy. It also raises issues of a trial court’s power to grant or deny anonymous speakers’ requests for protective orders. However, the majority opinion seems to avoid one issue: whether Cooley was required to give Doe 1 notice of the suit before the anonymity could be removed.

Congress shall not abridge the freedom of speech by unveiling “Rockstar05.” The First Amendment’s protection for anonymous free speech safeguards the user’s identity.

Doe 1 revealed himself only as “Rockstar05” on his self-created website entitled “THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW SCHOOL SCAM.” Doe 1 made derogatory statements about Cooley on the site, writing that it is a joke, the worst law school in America, and that its graduates are unemployed. After Cooley filed a complaint against Doe 1, the law school also sought to subpoena the defendant through Weebly Inc., owner of Doe 1’s website. The subpoena was a discovery request that would reveal the name of Doe 1. In response, Doe 1 attempted to quash the subpoena to protect his identity. After Weebly turned over the information, Doe 1 moved that the trial court to strike his identity because Michigan discovery rules allowed for his identity to be protected.

Because this was an issue of first impression for the state, the trial court looked to other jurisdictions in deciding whether to grant Doe 1’s motion to strike. It determined that it must balance Doe 1’s interests in remaining anonymous with Cooley’s interest in holding someone responsible for the defamation. The trial court reasoned that Doe 1’s statements were slander per se and did not invoke First Amendment protection. Cooley was allowed to use Doe 1’s identity, pending Doe 1’s appeal.

The Court of Appeals subsequently reversed and remanded the trial court’s decision. The Court of Appeals ruled that Doe 1 did have a right to protect his identity and that the issue was not moot considering that all documents containing Doe 1’s actual name were not further disclosed. There was also no indication that Doe 1’s name was otherwise obtained.

The Court of Appeals concluded that the trial court abused its discretion and erred in ruling that per se defamatory statements were not protected under the First Amendment. The trial court had assumed that Cooley would not have to prove the elements of defamation because Doe 1’s statements were defamatory on their face. This assumption led the trial court to adopt the wrong analysis when evaluating whether to issue a protective order. Overall, the trial judge erred in ruling to disclose the former student’s name without first considering his or her First Amendment right to protect anonymous free speech.

The Court of Appeals protected the speaker’s First Amendment rights, but did not address several important issues.

While the Court of Appeals made it clear that First Amendment rights are to be considered in protecting the anonymity of a speaker, it failed to resolve the issue of notice to such speakers. The Court of Appeals declined to address the issue of notice, stating that the issue was the province of the state legislature or the Michigan Supreme Court. In this case, Doe 1 was put on notice only by seeing the press release that revealed Cooley’s lawsuit against him or her. Other appellate courts have decided that the plaintiff suing an anonymous defendant must give notice of the suit before the defendant’s identity may be revealed; however, Michigan did not address this topic in a clear manner. Lack of notice raises serious concerns as to how speakers will approach a pending lawsuit and a subpoena requesting their identity when they are not aware of either.

In addition to leaving out a clear notice standard, the majority opinion also fails to give a clear standard for how trial courts should determine when to give protective orders in the future. The court does not adopt the previous standards of Dendrite and Cahill. Both of these cases adopted standards to be applied when using the First Amendment to address protective orders in anonymous speaker cases, but here the court does not apply them directly.

Court of Appeals Judge Jane Beckering’s concurring opinion raises the issue of notice and urges Michigan to apply the standards adopted by other appellate courts in order to provide trial judges with more guidance. Judge Beckering suggests a clearer standard that would use a modified version of the Dendrite standard. This modified standard would allow a plaintiff to seek the identity of a defendant accused of defamation only if the following conditions are met: (1) reasonable attempts have been made to notify the defendant of the discovery requests and the defendant has had a reasonable chance to defend against the requests; (2) each element has been presented to the trial court supported by prima facie evidence, apart from those elements that require the defendant’s identity; and, (3) the strength of the plaintiff’s case along with the need to disclose the defendant’s identity is greater than the defendant’s right to speak freely and anonymously.

Overall, the ruling is a “mixed blessing for anonymous Internet speakers in future cases.”

Doe 1 was fortunate in that he or she was able to take the necessary steps to protect their identity after seeing Cooley’s press release. However, future defendants may not be as fortunate. Hopefully, future cases will take Judge Beckering’s concurrence into consideration in establishing a bright line rule in Michigan that will require notice.

While the Court of Appeals was successful in correcting the trial court’s attempt to dismiss First Amendment protection where it should be exercised for defamatory statements, the future of such anonymous free speech cases is uncertain. Although Judge Beckering’s concurrence gives some direction for a definite standard, the law for Michigan is still murky. Attorney Paul Levy, representing Doe 1, commented on the lack of guidance given by the court on future protective orders, stating that the ruling is “a mixed blessing for anonymous Internet speakers in future cases.” Although there is certainly some protection under the First Amendment, the bumpy road to the point of protection needs to be paved.