Ban on college newspapers from advertising alcohol ruled an unconstitutional violation of free speech

Two Virginia college newspapers emerged victorious after six long years of litigating their First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

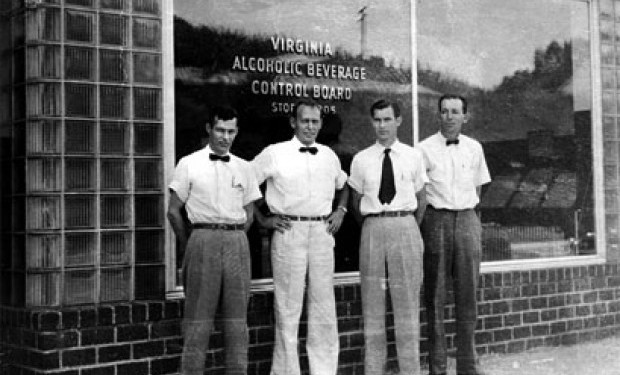

In June 2005, the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Board (ABC) issued a regulation prohibiting college student publications from printing alcohol advertisements unless the advertisement was in reference to a dining establishment. The regulation defined a college student publication as a publication distributed, or, intended to be distributed to, persons under twenty-one years of age. As a result, the American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia (ACLU) filed a lawsuit in federal district court in Richmond on behalf of two college newspapers, The Collegiate Times and The Cavalier Daily (the “College Newspapers”), at Virginia Tech and the University of Virginia, respectively.

The lawsuit against ABC alleged that the ban on alcoholic advertisements violated the College Newspapers’ First Amendment right to commercial speech. Mike Slaven, editor-in-chief of The Cavalier Daily, stated at the time that the “regulation forced them to turn down advertisers which deprived the paper of a significant source of revenue.” More recently, Rebecca Glenburg, Legal Director for Virginia’s ACLU, noted that the regulation put the newspapers at a competitive disadvantage to other local newspapers that were allowed to advertise the sale of alcohol. She added that “there was no evidence at all that this kind of regulation was effective at curbing underage drinking or binge drinking on college campuses.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit agreed and published an opinion on September 25, 2013, finding that the Virginia regulation was not appropriately tailored (pdf) to Virginia’s stated aim of curbing underage drinking.

For purposes of the First Amendment, advertising of alcohol falls within the context of commercial speech.

One of the primary freedoms under the First Amendment is the freedom of speech. Despite this general freedom to “speak,” a State is within its police power to regulate speech under certain circumstances. Depending on the type of speech, government regulations are scrutinized by courts to ensure that they do not infringe on this freedom any more than is necessary. The regulations that strike to the core of First Amendment speech, such as religious or content-based speech, are subject to strict scrutiny, while regulation of speech engaged in commercial activity is subject to the lesser standard of intermediate scrutiny.

Plaintiffs in a commercial speech case can have an uphill battle against the government because of the conflict between the lesser First Amendment protection provided commercial speech and the State’s interest in regulating this speech in the form of business transactions. For purposes of the First Amendment, advertising of alcohol falls within the context of commercial speech; however, a State government can regulate advertisements as a potential public health issue. To do this, the government must show that the advertisement has a direct and material effect (pdf) on alcohol consumption leading to abusive drinking.

The College Newspapers won the initial battle at the District Court level, which struck down the Virginia regulation as facially unconstitutional.

Over the six years of litigation, the Fourth Circuit heard several arguments about whether Virginia’s ban on alcohol advertisements was constitutional. When the suit was initially filed in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, the College Newspapers put forth three arguments: that the regulation was facially unconstitutional; that even if the regulation was facially constitutional, the regulation failed “as applied” to college newspapers; and that the regulation should be subject to strict scrutiny instead of the intermediate scrutiny typically applied to commercial speech.

The College Newspapers won the initial battle at the District Court level, which struck down the Virginia regulation in March of 2008 as facially unconstitutional (pdf). Having determined the regulation to be unconstitutional on its face, the District Court did not address the remaining two issues. However, the College Newspapers’ victory at the District Court level was short-lived when the Fourth Circuit, on appeal in 2010, reversed the judgment (pdf). The Fourth Circuit held that the regulation on its face did not violate the First Amendment and remanded the case back to the District Court to determine the two remaining issues of the constitutionality of the regulation as it was applied to the College Newspapers and whether strict scrutiny should apply.

On the second appeal, the Fourth Circuit applied the Central Hudson test and held that Virginia’s regulation to ban alcohol advertisements was unconstitutional as applied to school newspapers.

Virginia secured a victory on remand when the District Court, in refusing to apply strict scrutiny to the state’s regulation, ruled that the regulation did not violate Central Hudson as applied to the College Newspapers. In Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission of New York, the Supreme Court of the United States articulated a four-prong test to evaluate the constitutionality of a state regulation in the context of commercial speech. Under Central Hudson, a court will uphold a regulation if (1) the regulated speech concerns lawful activity and is not misleading; (2) the regulation is supported by a substantial governmental interest; (3) the regulation directly advances that interest; and (4) the regulation is not more extensive than necessary to serve the government’s interest.

On the second and more-recent round of appeals in 2013, the Fourth Circuit applied the Central Hudson test (pdf) and held that Virginia’s regulation to ban alcohol advertisements was unconstitutional as applied to school newspapers. In the court’s analysis, the regulation easily passed the first three prongs of Central Hudson. First, all parties agreed that the regulated speech—alcohol advertisements—concerned the lawful activity of alcohol consumption and there was no dispute that the advertisements were misleading in any way. Second, the Fourth Circuit held that the governmental interest was substantial. All parties agreed that Virginia had a substantial state interest in battling underage and abusive drinking on college campuses. The regulation also satisfied the third prong because it served to advance Virginia’s interest of decreasing alcohol consumption by college students by decreasing alcohol advertising.

The Fourth Circuit found that the District Court erred in concluding that Virginia’s regulation satisfied the fourth Prong of Central Hudson.

The Fourth Circuit found, however, that the District Court erred in concluding that Virginia’s regulation satisfied the fourth prong of Central Hudson. The court noted that the regulation kept legal “would-be drinkers” in the dark based on what ABC perceived to be their own good. Thus, the District Court erred in “concluding that the challenged regulation was appropriately tailored to achieve its objective to reduce abusive college drinking.”

Virginia’s ban on alcohol advertising as applied to the College Newspapers failed the fourth prong of Central Hudson because the court found the regulation more extensive than necessary to serve the government’s interest. In its ruling, the Fourth Circuit noted that the regulation prohibited people over the age of twenty-one from receiving truthful information about a product they are legally allowed to consume. Since over sixty percent of the readers for both newspapers were over the age of twenty-one, the regulation was unconstitutionally overbroad. The court added that the “College Newspapers had a protected interest in printing non-misleading alcohol advertisements, just as the majority of readers had a protected interest in receiving that information.”

In her victory speech, Kelly Wolff, general manager of Educational Media Company, which owns The Collegiate Times, stated that it was “worth noting that this First Amendment ruling comes even as the speech was classified as commercial speech and subject to less stringent protections than non-commercial speech.” She added that “although nobody has been arguing that it is not a good goal to prevent underage drinking…we think this was an important First Amendment victory for the College Newspapers.”