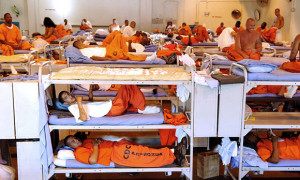

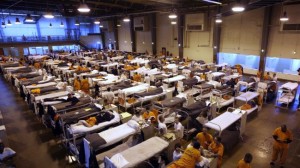

Prisons in the United States are overcrowded. The federal prison system is estimated at forty percent over capacity, to be exact, with male-only prisons gauged to be at an even higher percentage of overcrowding. State prisons are beyond their limits as well, with the North Carolina Sentencing Advisory Committee estimating (pdf) that the state’s prisons are, and will continue to be, well over capacity by thousands of prisoners.

Prisons in the United States are expensive. The average annual cost of holding an inmate in federal prison was $28,893 in 2011, and that number has steadily been on the rise. In North Carolina, the annual cost for minimum custody state prison inmates in 2012 was $24,042, and that number jumped to $27,674 and $33,317 for medium and close custody inmates, respectively.

These numbers draw us to what would seem to be the only rational conclusion: violent crime is on the rise in our nation, and the government and prison system are doing all they can to keep up. Deductive reasoning fails us, however, as violent crime in our nation is headed toward record lows.

This schism in the correlation between violent crime rates and prison overcrowding has led some key figures, such as Attorney General Eric Holder, to question the current sentencing practices.

“The war on drugs is now 30, 40 years old. There have been a lot of unintended consequences.”

As the leading law enforcement officer in our nation, there is no doubt that Attorney General Holder recognizes the crucial role that incarceration plays in the country’s justice system. But in a speech given to the American Bar Association in August of this year, he pushed for sentencing reform, noting, “…widespread incarceration at the federal, state, and local levels is both ineffective and unsustainable. It imposes a significant economic burden, totaling $80 billion in 2010 alone – and it comes with human and moral costs that are impossible to calculate.”

As Attorney General Holder looks to sentencing trends of the past few decades, discerning how our country got in this dilemma is not too difficult. “The war on drugs is now 30, 40 years old,” he says. “There have been a lot of unintended consequences.”

In discussing an interview with Attorney General Holder, Daniel Klaidman, national political correspondent for Newsweek and The Daily Beast, also recognized the point at which “tough on crime” became too tough, and spiraled out of control:

The trend had begun with Richard Nixon’s War on Crime, and accelerated under the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, when conservative academics were spinning theories of irredeemable ‘super-predators’ and positing that IQ, genetics, and even race preordained criminal behavior. The conclusion of such thinking: criminals could not be deterred nor rehabilitated, but incarcerating them for long periods of time was the surest way of lowering crime rates.

In discussing a plan of action for the sentencing concerns, Attorney General Holder conceded that he and other members of the Executive Branch have some control over the matter. Holder acknowledged that his branch “can certainly change [its] enforcement priorities,” but also called for action from the legislative branch. The Attorney General stated that rethinking the deployment of agents as well as altering the charging instructions given to prosecutors are ways in which his division can move toward reform. In order to effectuate a real change in the system, however, Holder says the two branches need to “work together to look at this whole issue and come up with changes that are acceptable to both.”

Sentencing reform may be that seldom reached common ground between the ever-clashing parties of the legislative branch.

While Attorney General Holder’s goal for the government sectors is amiable, it can be hard to believe—in the current political climate—that the ever-clashing parties of the legislative branch will ever come together in agreement of what the states need. Sentencing reform, however, just may be that seldom reached common ground.

Some may think that talk of sentence-reducing reform would haunt the Democratic Party with flashbacks of the “soft on crime” mantra that threatened the party in the 1980s and ‘90s, but the issue is proving to be truly bipartisan. Even staunch conservatives are recognizing that it is no longer about being “tough on crime,” but instead, being smarter on crime.

“You know a transformational moment has arrived when the Attorney General of the United States makes a highly anticipated speech on a politically combustible topic and there is virtually no opposition to be heard.”

Two recently introduced bills, the Smarter Sentencing Act and the Justice Safety Valve Act, are evidence of this bipartisan concern over sentencing reform. Senators from both the Democratic and Republican parties authored each of the bills.

The Smarter Sentencing Act, introduced by Senators Richard Durbin (D-IL) and Mike Lee (R-UT), would lower federal mandatory minimum sentences, grant judges more discretion, and make individualized review for drug sentences more frequent.

The Justice Safety Valve Act, introduced by Senators Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Rand Paul (R-KY) in the Senate (and its counterpart in the House), would give judges leniency in sentencing federal offenders below the mandatory minimum period “whenever that minimum term does not fulfill the goals of punishment.”

These bipartisan bills and Attorney General Holder’s speech are garnering considerable attention for the issue of sentencing reform, and the consensus across the nation cannot be denied. “You know a transformational moment has arrived when the Attorney General of the United States makes a highly anticipated speech on a politically combustible topic and there is virtually no opposition to be heard,” the New York Times Editorial Board wrote, speaking of Attorney General Holder’s speech on the proposed reforms.

“By building more prisons and incarcerating more people, we’ve taken criminals off the street.”

But just when it seems as though there could be no logical challenge to the reform, no heralding voice in resistance, an unsettling quandary arises: perhaps the nation’s record-low crime rate is a product of the prolonged incarcerations. “By building more prisons and incarcerating more people, we’ve taken criminals off the street,” says Ted Kirkpatrick, a professor and criminology expert at the University of New Hampshire.

Although lengthy prison terms may play a minor role in explaining the declining crime rate, Kirkpatrick and others who have studied the subject agree that there are numerous other factors that likely had far greater contribution. Research tends to show that crime rates fluctuate more based on economic trends and demographic shifts than due to the amount of prisoners at any given time.

There is serious hope that sentencing will no longer be what one federal judge described as spinning the “Wheel of Misfortune.”

The link between crime rates and length of incarceration being so heavily disputed, and with such abundant need to fix the overcrowded, underfunded prison system, it is likely that bills such as the Smart Sentencing and Justice Safety Valve acts will have promising futures in the legislature. With Attorney General Holder leading the effort to get “smarter” on crime, and backed by resounding support from all points on the political spectrum, there is serious hope that sentencing will no longer be what one federal judge described as spinning the “Wheel of Misfortune.”