Attorney-Client Privilege Versus the Public’s Right to Know

A redistricting plan that pleases everyone simply does not exist. As Justice Hudson put it in her dissent to the North Carolina Supreme Court’s most recent redistricting decision, “[R]edistricting litigation is virtually inevitable every ten years. . . .” But the controversy surrounding the General Assembly’s latest redistricting plan posed a unique question for the courts that casts new light on a centuries-old doctrine: the attorney-client privilege.

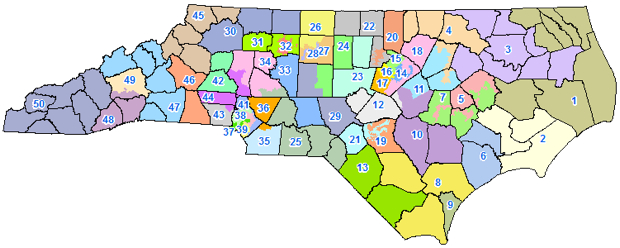

The story begins in early 2011. While formulating the latest redistricting plans, the Republican leadership of the redistricting committees in the North Carolina House and Senate received legal advice from the North Carolina Attorney General’s office, as well as two private law firms – Ogletree Deakins and Jones Day. The committee members were seeking advice to obtain preclearance under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, and (understandably) to prepare for potential lawsuits challenging the plans. The plans were enacted in July 2011, and received final administrative preclearance from the United States Attorney General in December. Meanwhile, opponents of the plans filed suit in November seeking an injunction to prevent elections from being conducted under the new plans.

During discovery, the plaintiffs requested the production of various communications related to the creation of the redistricting plans. But the legislative defendants refused to produce certain categories of documents, in particular a series of emails between the committee members and the lawyers in the Attorney General’s office and the two private firms. As justification for their refusal, they cited the attorney-client privilege and work product doctrine. The plaintiffs then filed a motion to compel discovery, citing section 120-133 of the North Carolina General Statutes. The statute reads:

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, all drafting and information requests to legislative employees and documents prepared by legislative employees for legislators concerning redistricting the North Carolina General Assembly or the Congressional Districts are no longer confidential and become public records upon the act establishing the relevant district plan becoming law.

Here lies the heart of the controversy: Does the common-law attorney-client privilege trump what appears to be a statutory waiver of confidentiality? The plaintiffs argued that in enacting this statute, the General Assembly had waived all privileges that could shield redistricting communications from the public view once the plan became law.

In April 2012, a three-judge panel of Superior Court judges granted the plaintiff’s motion to compel, concluding that the General Assembly “expressly waived any and all such privileges once those redistricting plans were enacted into law.” The panel further concluded that counsel from Ogletree Deakins, Jones Day, and any legislative staff attorneys were “legislative employees” for the purpose G.S. 120-133 because they were advising the General Assembly and were paid with state funds. However, the panel found that the waiver did not extend to communications with staff attorneys from the Attorney General’s office because they are not “legislative employees.”

The legislative defendants appealed directly to the North Carolina Supreme Court pursuant to G.S. 120-2.5. They argued that section 120-133 should be strictly construed as a narrow waiver of only the legislative confidentiality codified in the General Statutes, not the common law attorney-client privilege or work product doctrine.

The Supreme Court held that G.S. 120-133 does not waive either privilege “because the section in no way mentions, let alone explicitly waives, the attorney-client privilege or work-product doctrine.” Given the sweeping language of the statute (“Notwithstanding any other provision of law…”), the Court’s decision seems surprising at first glance. But the Court pointed out that in three other places in the Statutes, the General Assembly had waived the attorney-client privilege by mentioning it explicitly. Further, the Court looked to Black’s Law Dictionary for the definition of “provision”: “[a] clause in a statute, contract, or other legal instrument.” This definition, says the Court, suggests that the word “provision” refers only to statutes, not to the common law. Looking to the statute’s context, the Court held that the chapter in which 120-133 is located, entitled “Confidentiality of Legislative Communications”, was intended to “protect legislative communications from disclosure so as to preserve the integrity of the legislative process,” not to encourage disclosure as the Public Records Act does.

Justice Hudson disagreed with the majority’s analysis. She reasoned that the basis for the attorney-client privilege is confidentiality, and thus it protects only confidential communications. G.S. 120-133 explicitly states that redistricting communications “are no longer confidential” once the plan is enacted. From Justice Hudson’s view, “[t]his case does not concern a broad waiver of various privileges – the nonconfidential communications in question are simply beyond the protection of the attorney-client privilege, even if they once were protected.”

Justice Hudson also takes issue with the trial court’s order that the parties work together and “agree among themselves a reasonable means of identifying categories of documents that ought to remain confidential.” She suggests that the appropriate remedy falls between the trial court’s hands-off approach and the Supreme Court’s strong stance on attorney-client privilege – an in-camera review by the trial court to determine whether certain communications are “concerning redistricting” and thus subject to discovery by the plaintiffs.

According to the dissent, the redistricting committees were attempting “to protect much of their legislative redistricting work from public scrutiny under the cloak of attorney-client privilege.” The legislative defendants state in their brief that they disclosed thousands of documents in response to the plaintiff’s discovery request, and that the communications withheld constitute only a small fraction of the documents relating to the redistricting plans. But what did those withheld communications contain? Does this mean that future redistricting committees can shield some of their work from the public eye simply by seeking advice from outside counsel?

Maybe we will learn more in another ten years.