Brendan Dassey’s interrogation brings attention to false juvenile confessions

Juveniles are psychologically susceptible to being coerced into false confessions and yet there are few safeguards in place to prevent these confessions.

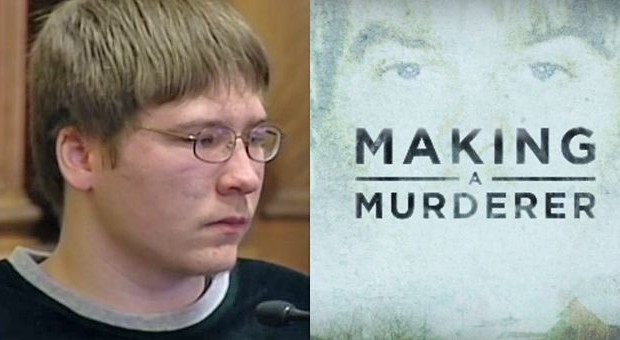

The widely popular Netflix documentary, “Making a Murderer,” examines the 2007 conviction of Wisconsin native, Steven Avery. Mr. Avery, as portrayed in the documentary, had a particularly troubling and convoluted relationship with the criminal justice system. The series begins with Avery’s 1985 conviction for sexual assault, for which he served 18 years before DNA evidence exonerated him. Two years after his release, Avery was arrested again and convicted for the murder of a young photographer, Teresa Halbach. Unexpectedly, viewers discovered that another Avery family member would be implicated in the murder.

Avery’s 16-year-old nephew Brendan Dassey was interrogated by police several times and eventually confessed to being involved in Halbach’s murder. There continues to be speculation about Avery’s guilt or innocence, yet the confession of his alleged co-perpetrator, Brendan, appears noticeably coerced. Brendan’s confession is now shining a light on the widespread problem of false juvenile confessions.

The story Brendan provides during his interrogations has him helping his Uncle Steven first sexually assault Halbach and then murder her

Documentary viewers were able to watch Brendan’s videotaped confession as a result of a July 2005 ruling by the Wisconsin Supreme Court that required police electronically record all interrogations of minors. As a result, critics of the confession have emerged.

Many viewers have criticized Brendan’s confession, noting that the videotaped confession shows the police manipulating him into giving a false confession to the murder. In his initial interview with police, which led to a confession, Brendan did not have a lawyer present. Also, Brendan appears to be a quiet teen, had an IQ that puts him near the range for intellectual disability, and was clearly confused by the entire situation he found himself in. The documentary shows how the detectives fed Brendan information about the crime and with no guidance of a lawyer; many people believe he simply gives the police what Brendan thinks they want.

The story Brendan provides during his interrogations has him helping his Uncle Steven first sexually assault Halbach and then murder her. Yet, there is no forensic evidence supporting the gruesome story from the interrogation. Further, in parts of the recording, it is evident that the detectives, not Brendan, are providing the vast majority of the details of the murder. In a taped phone call with his mother after the interrogation, Brendan tells her that he guessed at what the detectives wanted him to say, just like he guesses at his homework.

The extent to which Brendan does not understand the seriousness of what he is doing by confessing to the rape and murder of a woman is demonstrated by his question at the end of the interrogation—he asks detectives how much longer it will take because he has a school project to turn in that afternoon. He thinks that if he gives the police what they apparently want from him, he will be able to go back to school.

Brendan’s post-conviction attorneys argued that Kachinsky’s maneuvers violated his duty of loyalty to Brendan as his attorney and represented steps to essentially coerce Brendan into pleasing guilty

In an interview with People Magazine, Steven Avery’s defense attorney, Dean Strang, called Brendan’s narrative one “that physically couldn’t have happened, that physically was contradicted by the trace evidence.”

Brendan said in the March 2006 interrogation that he raped Halbach when she was tied to Avery’s bed, with ropes and chains, and that Avery had cut off all of her hair; that he himself slit her throat; that he and Avery then shot Halbach, both in the stomach and finally in the head. The events allegedly took place within Avery’s trailer and garage. Police did not find evidence, such as rope fibers, Halbach’s hair, sweat, or blood, in either location to support Brendan’s testimony.

Brendan’s first court appointed lawyer, Len Kachinsky, also placed him at a disadvantage. Mr. Kachinsky is thought to have placed the prosecution’s interests above those of his client. After allowing Brendan to be interrogated alone in March 2006, Kachinsky arranged for Brendan to be questioned again by his personal investigator. The documentary presents a videotape of the interaction, in which the investigator refuses to accept Brendan’s detailed alibi and instead coaches him to corroborate his earlier confession, instructing him to draw a series of pictures of the “crime scene.”

The incident with his investigator spurred Kachinsky’s removal from the case. Brendan’s post-conviction attorneys argued that Kachinsky’s maneuvers violated his duty of loyalty to Brendan as his attorney and represented steps to essentially coerce Brendan into pleasing guilty.

Although Kachinsky was dismissed for his role in the coercive interrogation, the testimony he provided was not and was ultimately used to convict Brendan. Notably, his uncle, to whom Brendan allegedly functioned as an accomplice, had previously been found not guilty of mutilating a corpse. The confession used to convict Brendan included that he and his uncle burned Halbach’s body. Critics point out that this was clearly contradictory. Despite Brendan’s attorney’s efforts, the jury found the confession to be true.

Drizin [Brendan’s post-conviction lawyer] concludes that there are definite markers of a false confession in Brendan’s case

It is difficult for the average person to understand why someone could confess to a crime they didn’t commit, especially a crime as horrific as the murder of Halbach. In an interview with Chicago Tonight, Steven Drizin, Brendan’s post-conviction lawyer, discussed the issue of false confessions: “What we’ve learned is they come from two things: one, aggressive coercive police interrogations; two used upon people with vulnerabilities that make them suggestible and scared.”

Drizin described Brendan as having been taken advantage of by everyone in the system, including the police who interrogated him by preying on his vulnerabilities and his defense lawyer who believed Brendan was guilty. His presumption of innocence was stolen from him, making it virtually impossible for him to have a fair trial.

Every time Brendan was interrogated his story was different. Drizin explained that this is common in false confessions. “Their story is inconsistent in the objectively knowable evidence of the crime, and when they tell it they can’t tell the same story twice.” Drizin concludes that there are definite markers of a false confession in Brendan’s case.

[I]n the last 25 years, 38 percent of exonerations for crimes allegedly committed by youth under 18-years-old involved a false confession

If Brendan’s confession is in fact false, he is not alone. False confessions are not uncommon in the United States criminal justice system. In a study by the Innocence Project of 225 wrongful-conviction cases cleared by DNA, 23 percent were based on false confessions.

For juveniles, the false confession rate is even higher. In 2013 the Innocence Project reported that data from the National Registry of Exonerations shows that in the last 25 years, 38 percent of exonerations for crimes allegedly committed by youth under 18-years-old involved a false confession.

Numerous studies have examined why traditional interrogation techniques might lead to a heightened risk for false confessions by juveniles. Some of these reasons include: (1) juveniles are more susceptible to suggestion from the leading and repeated questioning regularly used by police; (2) juveniles might have difficulty comprehending the adult language or complicated questions asked during interrogations; and (3) juveniles are more likely to concern themselves with short-term, rather than long-term consequences of the interrogation—they are more susceptible to the deception about the presence of (nonexistent) evidence, and they can be more eager to please adults (the police).

Further, juveniles also fail to understand their Miranda rights or how those rights are applied. In Brendan’s case, it was reported that he waived his Miranda rights but it is questionable that he actually knew what rights he was waiving.

Providing more safeguards for juveniles, such as requiring the presence of ideally an attorney may help a juvenile understand the severity of the situation

There are many psychological reasons why minors are especially susceptible to being coerced into false confessions, but there are also practical matters that concern how police interrogate juveniles.

Many states, such as Wisconsin, require that juvenile interrogations be recorded. However, it is not required that a parent be present when a juvenile is interrogated in Wisconsin; the failure to have a parent present is only one factor the court’s look at to determine if a confession was coerced. Having an attorney present is also not required in Wisconsin. In fact, few states require an attorney to be present during juvenile interrogations.

Providing more safeguards for juveniles, such as requiring the presence of ideally an attorney may help a juvenile understand the severity of the situation. In addition, specific training for police officers on how to question juveniles, including considering their psychological development, would help avoid false confessions.

Brendan Dassey is currently serving a life sentence at Green Bay Correctional; although his lawyers have filed a federal habeas corpus petition in hopes of getting his conviction vacated after a failed attempt at an appeal. Brendan Dassey’s taped confession has been thrown into the spotlight and has created a discussion about false and coerced juvenile confessions. This attention will hopefully not only help Brendan as many continue to search for the truth behind his case, but also bring about changes in the interrogation process that will protect other juveniles.