Draw up the battle lines

As the latest appeal to the Supreme concerning North Carolina’s redistricting plan heats up, familiar lines are drawn in the sand between Democrats and Republicans.

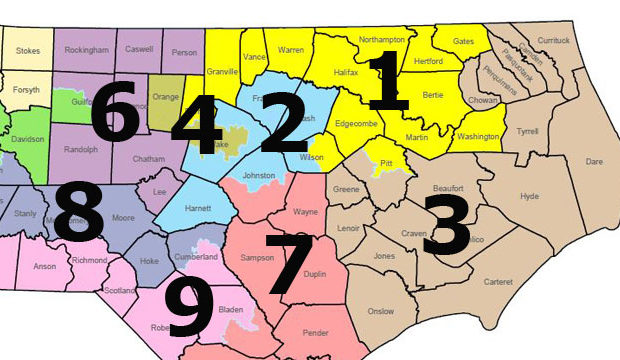

A North Carolina redistricting plan is yet again before the Supreme Court of the United States after SCOTUS recently agreed to hear an appeal of the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina’s decision in McCrory v. Harris. The lower court’s opinion, which held that North Carolina’s District 1 and District 12 were unconstitutionally drawn and ordered immediate redrawing, is being challenged for having misapplied both the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) and the standard of scrutiny for racially motivated redistricting plans. Deeper political divisions are also at work, as North Carolina’s Republican majority General Assembly stands accused by Democrats of using racially suspect gerrymandering to maintain political control.

The great irony of this case is how much the VRA has come to be used for political gain since its enactment in 1965. Originating out of the Democratic Party’s wooing of minority voters in the 1960s, the VRA’s language provides protections for the voting rights of racial minorities. Contained within section two of the VRA is a guarantee that “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision in a manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” Violations of the VRA are determined through a totality of the circumstances test that determines whether or not minority voters have essentially been given less opportunity by their state legislatures to participate in the political process than the rest of the electorate.

Though the Court has ruled that majority-minority districts are allowed under the VRA, there is a framework for determining whether a majority-minority district so dilutes the political power of a minority that it must be held unconstitutional.

One of the many ways in which the VRA has been implemented is through “majority-minority” districts, in which minority voters make up a numerical majority within a single voting district. SCOTUS has ruled that majority-minority districts are allowed by the VRA, and may be required in some cases. These districts were originally designed to ensure the election of more minority representatives, and has worked quite well. In the U.S. House of Representatives for example, since 1965 the number of black representatives has risen from 5 to 43. However, many criticize majority-minority districts as easily corruptible. Critics point out that majority-minority districts can be used in gerrymandering schemes to dilute the presence of minority voters in other districts.

Though the Court has ruled that majority-minority districts are allowed under the VRA, there is a framework for determining whether a majority-minority district so dilutes the political power of a minority that it must be held unconstitutional. That framework originated from a SCOTUS opinion written by Justice William Brennan in Thornburg v. Gingles, but was perhaps best articulated by Justice Anthony Kennedy in Bartlett v. Strickland, another North Carolina lawsuit in which the Court struck down a voting district plan by a Democratic majority in the General Assembly to take portions of several counties and make a majority-minority district out of those portions. In Bartlett, Kennedy discussed three “threshold requirements” necessary for implicating section two of the VRA and allowing the state to create majority-minority districts. First, the number of minority voters in the district must equal 50 percent plus 1, or a numerical majority. Second, the minority group must be “politically cohesive,” essentially meaning the minority group must share political interests. Finally, the majority must vote as a bloc so as to usually defeat the minority’s preferred candidate. If all the threshold requirements are met, then the totality of the circumstances are considered next to determine whether the state in question has violated section two of the VRA. For purposes of the VRA, intent does not matter, only whether there was a discriminatory effect. If race is implicated by that discriminatory effect, strict scrutiny is triggered, and the state in question must provide a compelling government interest that supports their need to draw district lines based on race.

The Middle District opinion seems to gloss over the threshold requirements, paying them little to no mind, but the fact that redistricting was unnecessary as minority voters usually elect their preferred candidates would seem to be a significant bar to the General Assembly’s redistricting plan.

The central focus of McCrory v. Harris is whether in redrawing North Carolina voting districts 1 and 12 into majority-minority districts, the General Assembly unconstitutionally diluted minority voters’ political power. It is important to understand that both Districts 1 and12 were not just arbitrarily redrawn into their current shapes. Their current form originates out of wildly misshapen majority-minority districts drawn in 1991 by the General Assembly. Both districts were drawn based on racial demographics, ostensibly to empower minority voters in regions where they were concentrated. However, concentrating minority voters in districts 1 and 12 was ruled unconstitutional by the Court in Shaw v. Hunt. In that case the majority determined that race was the “dominant and controlling” consideration in deciding where to draw voting district lines. Furthermore, the Court held that the North Carolina General Assembly did not have a compelling government interest in using race to draw voting district lines. Interestingly, in that case the five justice majority was made up of conservative bloc justices, while all four liberal bloc justices dissented.

In deciding McCrory v. Harris at the lower level, the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina made several findings. The decision discusses the Gingles threshold requirements, finding over 50 percent minority voters in both District 1 and District 12, as well as politically cohesive interests among the minority group. Interestingly, when discussing the third threshold requirement, that the majority vote as a bloc to usually defeat the minority group’s preferred candidate, it is mentioned that usually minority preferred candidates are the ones elected in District 1 and District 12. The Middle District opinion seems to gloss over the threshold requirements, paying them little to no mind, but the fact that redistricting was unnecessary as minority voters usually elect their preferred candidates would seem to be a significant bar to the General Assembly’s redistricting plan. Still, the Middle District’s majority opinion went on to discuss whether race was a dominant and controlling consideration in redistricting, and if so whether the General Assembly’s redistricting plan was narrowly tailored enough to be constitutional. The Middle District majority found that, in spite of claims that the redistricting was based entirely on partisan political goals, race was heavily involved as a factor in how District 1 and District 12 were redrawn. The lower court also found that the plan was not narrowly tailored, therefore ruling against the General Assembly.

What will be fascinating about McCrory is how the Court responds to a reversal, in which a now Republican controlled General Assembly has allegedly been unconstitutionally manipulating voting district boundaries.

In the Supreme Court, the discussion will likely center around whether race was a dominant and controlling factor in redistricting and whether the threshold requirements were met by the State. However, notice that up to this point, every case mentioned in this article other than the currently pending McCrory v. Harris has pitted the Court against a Democrat controlled North Carolina General Assembly attempting to manipulate voting districts for political benefit. What will be fascinating about McCrory is how the Court responds to a reversal, in which a now Republican controlled General Assembly has allegedly been unconstitutionally manipulating voting district boundaries. Will this case end up like Shaw, with voting split on strict ideological grounds? Or will both sides stick to their guns, with the conservative bloc standing against any form of discrimination based on race, which as Justice Clarence Thomas so famously wrote “the Constitution abhors?” It will be interesting to see where the votes fall when the Court decides this case.