Elonis v. United States: SCOTUS Determines Mental State is Necessary to Distinguish the Bad Acts From the Innocent

In another 8-1 decision, the Supreme Court of the United States chooses to withhold First Amendment analysis in this true threats case, but instead held that 18 U.S.C. § 875(c) requires a defendant intend to communicate a threat to be guilty of communicating threats via interstate commerce.

We are all aware of Eminem’s rapper alter ego, Slim Shady, and his vulgar rap lyrics, but what happens when someone makes threatening, directed statements over social media and masks them as “expressive rap lyrics?” On June 1, 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States held that unless the statements were made consciously and intentionally, the conduct cannot be criminal.

The Elonis v. United States case deals with specifically this situation. In May of 2010, Anthony Elonis’ wife of nearly seven years left and took with her the two young children the couple had together. After this event, Elonis began listening to more violent music and began creating his own rap lyrics.

These rap lyrics were written by him and were posted on his social media Facebook page. He created a rapper name, “Tone Dougie,” and even posted disclaimers under his lyrics that they were “fictitious” and had “no intentional resemblance to real persons.” The lyrics contained vulgar language, as well as violent and graphic imagery.

The first instance that spawned the lawsuit was a post he made after a Halloween Haunt event at his work with himself and a co-worker dressed up in costume, and Elonis was holding a knife to the co-worker’s neck. The caption of the photo said, “I wish.” After seeing this photo, the chief of park security fired Elonis form his job. In response, Elonis posted a threatening Facebook post about coming to the park and that nothing could stop him from getting there because he was a mad man.

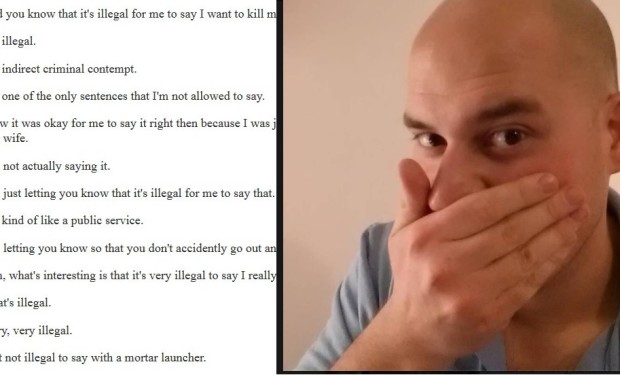

Elonis made statements such as, “Did you know that it’s illegal for me to say I want to kill my wife?”

Many posts were made regarding his ex-wife. The second instance that was mentioned in the lawsuit was a post he made where he quoted a video of a comedian where the comedian consistently stated how it is illegal to say that someone wants to kill the president. Elonis made statements such as, “Did you know that it’s illegal for me to say I want to kill my wife?” He also made statements such as “I also found out that it’s incredibly illegal, extremely illegal to go on Facebook and say something like the best place to fire a mortar launcher at her house would be from the cornfield behind it because of easy access to a getaway road and you’d have a clear line of sight through the sun room.” This post made his ex-wife feel afraid for her life and threatened.

In response, she was granted a three-year protection-from-abuse order against Elonis. However, in response, which is the basis for the third instance mentioned in the lawsuit, Elonis made comments such as “[f]old up your [protection-from-abuse order] and put it in your pocket … Is it thick enough to stop a bullet?” The post continues to threaten the State Police and Sherriff’s Departments with threats of explosives.

Another comment made by Elonis was regarding elementary schools and initiating “the most heinous school shooting ever imagined.” The statements caught the attention of the FBI and after a visit by the FBI agents, yet another post was made threatening the agents that came to his home, specifically a female agent, with knives and bombs that he claimed were strapped to him in the post.

Elonis claimed the posts were fictitious and were just rap lyrics. He claimed the posts allowed him to deal with the pain of his wife leaving and taking their children, and with all that was going on in his life. He also made First Amendment protection claims that the Supreme Court does not expressly rule on.

He was indicted for making threats to injure patrons and employees of his former place of employment, his estranged wife, police officers, a kindergarten class, and an FBI agent.

However, a grand jury indicted Elonis. He was indicted for making threats to injure patrons and employees of his former place of employment, his estranged wife, police officers, a kindergarten class, and an FBI agent. These statements were made in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 875(c), which states, “[w]hoever transmits in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to kidnap any person or any threat to injure the person of another, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.”

The District Court held that precedent had been set that only required that Elonis intentionally made the communication, not that he intended to make the threat. The jury instructions caused issue by stating that the jury could find Elonis guilty if they found that he intentionally made a statement in a context where a reasonable person would foresee that the statement would be interpreted by those to whom the statement was made as a serious expression of an intent to cause bodily harm or take the life of the person.

The Third Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the decision of the District Court. The Court of Appeals stated that the intent required by the statute is the only intent to communicate words that the defendant understands. Those words, too, that a reasonable person would view as threatening. Elonis appealed the Third Circuit decision claiming that the intent element in the statute requires that he intend for the communications to be threatening.

The Supreme Court decided to focus its analysis on the mens rea aspect, or the mental state aspect, of the statute as opposed to a First Amendment analysis of true threats.

The Supreme Court decided to focus its analysis on the mens rea aspect, or the mental state aspect, of the statute as opposed to a First Amendment analysis of true threats. Essentially, the statute requires that there be a threat communicated and transmitted via interstate commerce. The statute mentions no mens rea element and does not specify which, if any, mental state is required for a defendant to be convicted under the statute. The focus of the opinion is that there is no express requirement that the defendant intended that his communication contain a threat.

Elonis argues the fact that the word “threat” is in the statute would impose a requirement for intent on the defendant for the communication to be a threat. He also argues that in every statute where threat is mentioned, there is usually an intent element accompanying it. And, as such, it must be proven that he intended for his statements to be considered threats instead of lyrical statements for the purpose of artistic or therapeutic value.

The Government, on the other hand, argues that the statute should be read in light of the other provisions within the same statute that include an intent element. The other provisions of the statute prohibit certain types of threats, such as demand for ransom or reward, or extortion for money when threatening to kidnap or injure a person or threatening to injure the reputation of a person. Those provisions include an intent element where the defendant must intend to extort. The Government’s position is, essentially, because the fact that the other provisions within the same statutory section include an intent to extort, so too should the subsection of the statute at issue in this case.

However, the Court does not buy either party’s arguments. The Court disagrees with Elonis’ argument in that it focuses on the statement instead of the speaker. The Court disagrees with the Government’s argument in that it finds that the Congress’ exclusion of an “intent to extort” seems to mean that Congress did not intent to limit Section 875(c) to crimes of extortion, nor did it mean to exclude a requirement that a defendant act with a certain mental state when communicating the threatening statement.

There is a general notion reiterated in the opinion that “wrongdoing must be conscious to be criminal.”

The Court focuses its opinion on the idea that the fact that a criminal statute lacks a mens rea or lacks a mention of criminal intent does not mean that the statute should be read as entirely dispensing with such a requirement. There is a general notion reiterated in the opinion that “wrongdoing must be conscious to be criminal.” When a criminal statute lacks a scienter, or mens rea, requirement, the Court often interprets such a requirement into the statute.

The Court cites to multiple cases. One case that the Court sites throughout the opinion is the Morissette v. United States case where a man who took shell casings from a Government bombing range, without knowing the land to be Government property and believing those casings to have been abandoned. In this case, the statute contained a “knowingly converting” element, and the Court held that because he truly believed the casing to be abandoned, he could not be found liable.

Another case is Liparota v. Untied States, where the statute that made it a crime to knowingly possess or use food stamps in an unauthorized manner was deemed to require knowledge of the facts that made the use of the food stamps unauthorized for conviction under the statute. In Posters ‘N’ Things, Ltd. v. United States, the Court considered a statute prohibiting the sale of drug paraphernalia to read that an individual must know that the items were likely to be used for illegal drugs. Also, in X-Citement Video v. United States, the Court considered a statute criminalizing the distribution of visual depictions of minors engaged in sexually explicit conduct, but held that to be convicted under this statute a defendant must know that those depicted were in fact minors.

With this holding, essentially, a mental state will be read in to all criminal statutes lacking an explicit mental state in order to avoid criminalizing “innocent behavior.”

Upon consideration of those cases with the facts of the current case, the Court finds that there is a necessity that to be convicted under criminal statutes that are silent as to mental state, courts are to read in to the statute a mental state that is necessary in order to distinguish wrongful conduct from innocent conduct. With this holding, essentially, a mental state will be read in to all criminal statutes lacking an explicit mental state in order to avoid criminalizing “innocent behavior.”

The Court next considers the idea of the reasonable person interpretation with regard to how the statements, or Facebook posts in this situation, would be understood. The statute requires the communication of a threatening statement for the conduct to be wrongful. However, the statute gives no guidance as to how an allegedly threatening statement is to be interpreted to determine whether it is in fact threatening.

The Government, and the trial court, advocate for a “reasonable person” standard. This is the same standard utilized to determine civil liability, but is not consistent with the general requirement for criminal conduct, which requires awareness of some sort of wrongdoing.

The Court equates the use of a “reasonable person” standard to that of negligence liability. A negligence standard is just what the Government argues for by stating that Elonis can be convicted under the statute if he knew the contents of what he posted would be interpreted as threatening. Courts have been reluctant to hold for a negligence standard for criminal liability, and instead states that for criminal liability, what the defendant thinks does in fact matter.

The Supreme Court states that negligence is not enough to support a conviction under the statute.

The Supreme Court states that negligence is not sufficient to support a conviction under the statute. In doing so, the Supreme Court goes against nine of the eleven United States Courts of Appeals.

Two justices do not join the majority opinion. Justice Alito, while voting in the majority, writes a separate concurring and dissenting opinion. Justice Thomas is the lone justice who does not agree with the reasoning or the result of the Elonis case.

Justice Alito warns that what the majority has done is stated what the law is not, instead of what the law requires for a conviction under Section 875(c). In his analysis, he advocates for a reckless standard for whether the communication met the requirements for conviction under the statute. He states that a recklessness standard is sufficient because if the defendant consciously disregards the risk that the communication could be construed or seen as a threat, that should be enough for a conviction.

Justice Alito also brings up a main concern of many Americans upon hearing of this fact situation: what exactly is a true threat? He highlights Elonis’ argument that the First amendment protects a threat if the person does not actually intent to cause the harm in the communication. However, Justice Alito reiterates that whether or not the person making a threat intends to cause the harm, the damage caused is just the same, fear in the person to whom the communication is made. Justice Alito even attacks Elonis’ opinion that lyrics in songs are different than statements made on social media, and as such should not be considered the same.

Justice Thomas on the other hand dissents entirely and claims that this decision leaves lower courts to guess on what is necessary for conviction under the statute. He calls for a general intent standard attacking the argument made by the majority and instead claims that in the absence of mens rea, a general intent presumption is created where the defendant must know the facts that make his conduct illegal.

Justice Thomas mentions that even in states that have laws prohibiting the communicating and distributing of threats via commerce, there is a degree of intent.

Justice Thomas mentions that even in states that have laws prohibiting the communicating and distributing of threats via commerce, there is a degree of intent. He states that in most states where such a law exists, there exists a specific intent to extort element. He goes further and argues that the First Amendment has never protected true threats, and as such, there is always a risk that a criminal threat statute may suppress legitimate speech.

His analysis leads to the idea of many Americans following this case, that society does not tolerate or protect true threats, and as such, the risk of preventing some legitimate speech to be better able to prohibit true threats made against others is acceptable. The holding in this case certainly is pro-speech, but it also appears to be anti-victim in that it does not provide great protections to those who are targeted, or feel targeted and harmed, by posts made over social media depicting threatening language toward them.

[A] larger issue not highlighted in the majority opinion is the fact that the statements made were threatening statements that others believed were true threats directed at them or others.

While the Court cites to multiple cases, no case cited deals with threats. The cases to which the Court cites deal with statutes that have been interpreted that lack a mental state for the defendant. While the Elonis case certainly deals with a statute lacking a mental state for the defendant, a larger issue not highlighted in the majority opinion is the fact that the statements made were threatening statements that others believed were true threats directed at them or others.

This holding has it’s own set of issues. How is a prosecutor to show that a defendant’s behavior was not innocent when testimony from the defendant will be that of course he “didn’t mean it.” In instances such as the Elonis case, all he would have to do is say that he thought he was rapping or writing lyrics, when in fact maybe he was intending to incite fear in his ex-wife. This holding seems to do little to protect a person who feels legitimately threatened by comments made on social media. Instead, it appears this holding allows for more leeway for defendants to make threats and claim they’re just rap lyrics, or claim they’re just a way of rehabilitation and coping with issues they’re dealing with.

This begs the question of whether these cases should be used to assist in determining the case at issue. Should this case dealing with threatening statements be dealt with separately because of the potential for harm to others? Or was this done on purpose? If the Court were to interpret this case as an exception to the common interpretation of statutes of the like, would this open the door to other exceptions? But what many are concerned about is the lack of talk about the threatening nature of the statements made.

The decision still leaves open for consideration whether threatening posts made over social media are considered true threats…

What a majority of legal scholars and Americans were expecting out of the Elonis decision was more clarification on the true threats exception to the First Amendment free speech protections. What we got from the Supreme Court decision was no analysis of the First Amendment protections, but more of a focus on statutory application. The Supreme Court chose not to consider the facts of this case with the First Amendment, but focused their argument on the requirements of the statute. The decision still leaves open for consideration whether threatening posts made over social media are considered true threats, and it won’t be until more Facebook posts similar to those here are made that a decision might be rendered.

Why is that? The majority opinion says that it is not a necessary consideration for the facts of this case given the decision of the Court on the statutory decision. However, the concurring and dissenting opinions contain some First Amendment analysis. It seems the Supreme Court punted on the First Amendment issue for a more settled analysis.