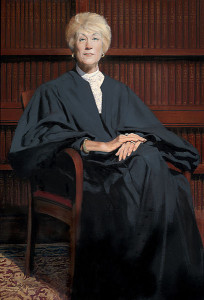

In October 2013, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit blocked Judge Shira Scheindlin’s order requiring changes to the New York Police Department’s stop-and-frisk program and removed Judge Scheindlin from the case. In August, after a two-month trial, Scheindlin ruled that the NYPD not only violated the Fourth Amendment’s guarantee against unreasonable searches and seizures, but had also violated the Fourteenth Amendment by resorting to a “policy of indirect racial profiling,” evidenced by the skyrocketing numbers of police stops in minority communities over the last ten years. The NYPD appealed her findings and remedial orders, including a decision to assign a monitor to help the police department change its policy and training program.

In its ruling, the Court stated that Judge Scheindlin needed to be removed from the case because she “ran afoul” of the code of conduct for U.S. judges by compromising the necessity for a judge to avoid the appearance of partiality. In its ruling, the panel of three judges criticized Judge Scheindlin for giving interviews and making public statements, which were published in The New Yorker and the Associated Press, while the case was pending before her. In these published interviews, Scheindlin spoke to reporters after the Bloomberg administration leaked statistics on her rulings against police in an attempt to show bias.

The judiciary panel has since recanted its misconduct finding, stating that “We now clarify that we did not intend to imply in our previous order that Judge Scheindlin engaged in misconduct.” But the Court’s revised order did not remove the damage to Scheindlin’s reputation, and, despite the less severe accusations, the panel stood by its decision to remove her.

The rule is usually used to send cases involving similar facts to a single judge in the interest of efficiency and economy, but it has also evoked concerns about “judge-shopping.”

In response to the appellate ruling, Scheindlin said she had taken the stop-and-frisk case, Floyd v. City of New York, only because it was “related” to another case she heard in 2007. She rejected the panel’s claim that she discussed the Floyd case in interviews conducted in the summer of 2013. The Court criticized her for suggesting to the challengers in 2007 that they file a new, “related case” rather than extending a 1999 settlement. Scheindlin was alluding to a rule that directed lawyers to route a lawsuit to a judge who is already hearing a case with similar facts. This “related case” rule is an exception to the practice of randomly assigning cases and is intended to simplify litigation. The rule is usually used to send cases involving similar facts to a single judge in the interest of efficiency and economy, but it has also evoked concerns about “judge-shopping.”

Judge Scheindlin told the lawyers that the issue might be better addressed by bringing a new case. “If you got proof of inappropriate racial profiling in a good constitutional case,” she said, “why don’t you bring a lawsuit?” The plaintiffs could designate the suit as related, and Judge Scheindlin would then presumably accept it as a related case. Judge Scheindlin admitted that the idea was problematic and was “sure [she was] going to get in trouble for saying it.” Despite these qualms, city lawyers did not object to her suggestion, nor did they object when Floyd v. New York was filed and marked as “related.”

The appeals court ruling will become moot if de Blasio does in fact withdraw the appeal or devises a settlement.

In response to Judge Scheindlin’s actions, Manhattan’s Federal District Court recently issued new rules to regulate the use of the related-case rule, including having all such requests reviewed by a three-judge panel. Chief Judge Loretta A. Preska said the goal was to “maximize the randomness” of assignments and “increase transparency.” The new rules will require any party that seeks to mark a lawsuit as “related” to another case before a judge to file a statement “stating clearly and succinctly the basis for the contention.” Moreover, any other party may object to a claim of relatedness in writing. Although a judge being asked to accept a “related” case will still independently make that decision, the court’s three-judge assignment committee, including the chief judge, will review every case where a claim of relatedness has been made. If the assignment committee disagrees with the judge’s decision to accept a case as related, the matter will be assigned randomly to a new judge.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio promised that on the first day of his administration, he would withdraw New York City’s appeal of sweeping reforms ordered by a federal judge in the Police Department’s stop-and-frisk practices. The appeals court ruling will become moot if de Blasio does in fact withdraw the appeal or devises a settlement.