Foreign Sovereign Immunity: A Shield for International Cybercrime Aimed At Economic Gain

Foreign sovereignties can currently commit acts of espionage against the United States without penalty by the federal government; however, a new bill seeking to amend the law will allow new sanctions against foreign hacker groups.

Editor’s Note: The Campbell Law Observer has partnered with Judge Paul C. Ridgeway, Resident Superior Court Judge of the 10th Judicial District, to provide students from his International Business Litigation and Arbitration seminar the opportunity to have their research papers published with the CLO. The following article is one of many guest contributions from Campbell Law students to be published in the Spring 2016 semester.

By: Lauren Travers, Guest Contributor

Spying, stealing, misappropriation, and conversion, are all words that can be used to define the dangers of the Internet. With expansive growth and worldwide electronic interdependence, individuals, businesses, and even countries are susceptible to these dangers. In fact, the majority of all sensitive economic information held by a corporation or a government entity can now be found online. Thus, criminal activity committed over the Internet has become incredibly prevalent. The performance of this criminal activity over the Internet is referred to as Cybercrime.

Spying, stealing, misappropriation, and conversion, are all words that can be used to define the dangers of the Internet. With expansive growth and worldwide electronic interdependence, individuals, businesses, and even countries are susceptible to these dangers. In fact, the majority of all sensitive economic information held by a corporation or a government entity can now be found online. Thus, criminal activity committed over the Internet has become incredibly prevalent. The performance of this criminal activity over the Internet is referred to as Cybercrime.

Cybercrime is not only committed by individuals, but sovereign nations have used this increase in technology to their advantage. While a majority of foreign sovereigns engage in spy tactics for intelligence purposes, some sovereigns have begun to use the Internet for more than just protecting the safety of their citizens. A number of foreign sovereigns use the Internet to steal secrets and disperse them among state-owned enterprises.

One major form of cybercrime used by foreign nations for economic gain is economic espionage—the act of knowingly targeting or acquiring trade secrets to “benefit any foreign government, foreign instrumentality, or foreign agent.” Economic espionage has an incredibly large impact on the United States economy every year. The Federal Bureau of Investigation estimates that such espionage costs the U.S. nearly $13 billion annually.

While economic espionage is often committed by independent hacking groups with the intent to sell the stolen trade secrets to government entities, government agencies themselves are also behind these acts of espionage. Under-resourced governments foster relationships with hacking groups to develop harmful software in an effort to steal sensitive U.S. economic or technological information. These governments then use the stolen trade secrets to obtain economic advantage within their state-owned industries.

Unfortunately, a foreign sovereign that has committed the crime of economic espionage currently may not be sued by the United States for two separate reasons. First, the United States Code, which codifies the act of economic espionage, only provides that an individual or corporation responsible for such espionage may be prosecuted. The Code does not speak to actions committed at the request of the foreign government. Additionally, foreign sovereigns who engage in economic espionage are immune from liability under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act.

Economic espionage is a federal crime

Economic espionage is defined as “whoever, intending or knowing that the offense will benefit any foreign government, foreign instrumentality, or foreign agent, knowingly” steals, copies, or buys a trade secret. A trade secret is any form “of financial, business, scientific, technical, economic or engineering information” that the owner thereof has taken reasonable measures to keep secret. Business and government entities are often the target of economic espionage as they hold sensitive economic information. The majority of this sensitive information is now created, used, and stored in cyberspace. Thus, economic espionage is increasingly committed by foreign entities through cyberspace, attempting to compete with their international adversaries.

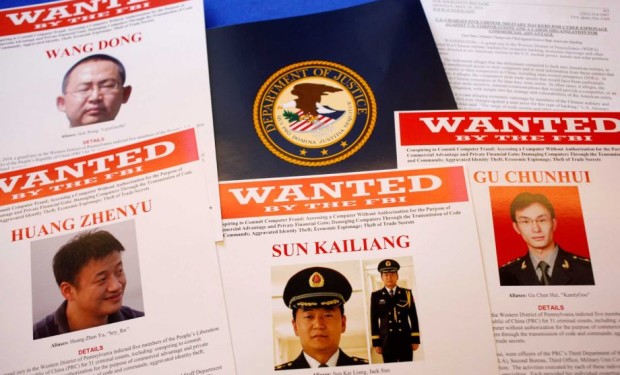

While international economic espionage is incredibly prevalent, the United States has never charged a foreign government with the crime. In 2014, five officers of the Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army were charged for espionage against six American companies. The hackers stole information that would be helpful to their competitors in China, including state-owned manufactures. This was the first time that the United States had sued state actors for the crime of economic espionage. However, the federal government did not sue these state actors in their official capacity, but rather they were sued in their individual capacities. The United States Assistant Attorney General for National Security, John Carlin, was quoted saying, “[s]tate actors engaged in cyber espionage for economic advantage are not immune from the law just because they hack under the shadow of their country’s flag.” Thus, while state actors are not immune from the charge of economic espionage in their individual capacities, the United States still holds that foreign governments are immune from this crime.

Proposed legislation would change the immunity granted to foreign sovereigns

A. Proposed legislation would hold foreign sovereigns liable for economic espionage.

While the crime of economic espionage may currently only be committed by individuals or corporate entities, a proposed bill could change that. The proposed bill is titled the International Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2015 (hereinafter the “Prevention Act”). It distinctly clarifies that the theft of trade secrets performed at the request of a foreign sovereign is unlawful economic espionage.

Currently, the United States law on economic espionage applies to acts taken knowing they will benefit a foreign government. It does not mention acts committed at the request of any government agency. The Prevention Act seeks to contain this language; specifically, the amended Code would be restated to include “or intending or knowing that the offense is committed at the request, under the direction, or on behalf of any foreign government, foreign instrumentality, or foreign agent.” The Prevention Act adds acts committed on behalf of or at the request of a foreign government to the definition of economic espionage, thereby extending liability to foreign sovereigns for the act of economic espionage.

B. Jurisdiction extends to foreign individuals and corporations through long-arm statutes.

While liability would be extended to foreign sovereigns as entities, a jurisdictional issue must still be answered. The act of economic espionage is often committed in a foreign state; thus, the United States court system would normally lack jurisdiction over these foreign violators. However, the codification of 18 U.S.C. § 1837, which extends liability for economic espionage to actions taken outside the United States, provides an answer to this jurisdictional issue. The federal government may sue a foreign violator for economic espionage where there is also an act in furtherance of the offense committed in the United States. Thus, hacking into an entity’s servers that are located in the United States would give federal courts jurisdiction over a claim of economic espionage committed in a foreign state.

Once in a United States court, the federal government may pursue civil or criminal action against an individual or organization that commits economic espionage. Under the United States Code, federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over such matters. An individual who commits espionage can be fined up to $5,000,000 or imprisoned up to than 15 years, or both. An organization that commits economic espionage can be fined up to the greater of $10,000,000 or three times the value of the stolen trade secret to the organization. The Attorney General may seek appropriate injunctive relief against either an individual or an organization.

C. Foreign sovereigns are currently immune from liability.

Moreover, while the Prevention Act extends liability for economic espionage to federal sovereigns, and the United States Code extends jurisdiction for its courts, foreign sovereigns still may not be brought into U.S. courts under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act is the primary means for suing a foreign sovereign or its agencies. It sets out procedures that must be followed in such a lawsuit; however, under the Act, foreign states are generally granted immunity from liability. The United States courts do not have jurisdiction over a foreign entity under the Act for several policy reasons. However, there are a few exceptions.

One exception to this immunity is applied when a foreign state commits a non-commercial tort. Under 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a), a foreign state is not immune from liability in an action for money damages as a result of personal injury, death, or damage to or loss of property. The injury or damage must occur in the United States and be caused by the tortious act or omission of the charged foreign state or of any agent of the state acting within the scope of his office. The exception is not applied to acts of a discretionary function, or a claim arising out of malicious prosecution, abuse of process, libel, slander, misrepresentation, deceit, or interference with contract rights.

Foreign sovereignties should not be immune from prosecution for economic espionage

Foreign sovereigns should no longer be protected under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act for acts of economic espionage. The United States faces economic hardship every year as a result of this illegal activity. When foreign governments steal United States’ trade secrets, they not only hurt the U.S., but they gain an unfair economic advantage.

While all countries spy on one another’s intelligence, this activity becomes unethical and illegal when countries spy for the sole purpose of economic gain. As an illegal activity, the act of economic espionage committed by a foreign sovereign should be prosecuted by the United States courts. Furthermore, the courts should have the jurisdiction to prosecute foreign sovereigns for such acts because economic espionage involves the tortious act of conversion, which is excepted from the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act.

The act of conversion is legally defined as “an unauthorized assumption and exercise of the right of ownership over goods or personal chattels belonging to another, to the alteration of their condition or the exclusion of an owner’s rights.” Put simply, conversion involves a physical invasion of one’s property rights that is so serious it ruins the value of the property to the true owner. Not every interference with property rises to the level of conversion, but where property essentially loses its value after being stolen, the act of stealing the property is deemed conversion. The tortious act of conversion allows the owner to ask for new property or claim money damages where the original property cannot be replaced.

The tortious act of conversion applies to economic espionage. Economic espionage involves the act of knowingly stealing, copying, or buying a trade secret. As previously described, a trade secret is information the owner of which takes reasonable measures to keep private. By law, a trade secret is considered valuable property that can be converted where the true owner had taken reasonable measures to protect it. Further, where trade secrets constitute instruments of commercial competition, those who develop them will be afforded the protection of law. One such form of protection provided to trade secrets is the remedy for conversion. When a trade secret is stolen, the value of such property is diminished so severely as to effect a conversion. This is because the value of a trade secret is in its privacy; where everyone knows the secrets being kept, the trade secret is essentially useless. Therefore, when a foreign sovereign is committing an act of economic espionage by stealing a trade secret, it is also committing an act of conversion.

A tortious act of conversion, committed by a foreign sovereign, falls within the jurisdiction of the United States Court System. Under the United States Code, the act of conversion is an exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. Specifically, conversion committed by a foreign sovereign is a non-commercial tort. When suing another for conversion, one may seek a new good or money damages. These money damages are the result of a loss of property. Where the act of conversion occurs within the United States, it may be deemed an exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act as a non-commercial tort.

In the case of economic espionage, where a foreign sovereign steals a trade secret from electronic servers maintained in the United States, the foreign sovereign is committing an act of conversion that falls under the exception to Foreign Sovereign Immunity. In doing so, the United States Court System has jurisdiction over the foreign sovereign for this act of conversion. Moreover, where a court has jurisdiction over a foreign sovereign for the claim of conversion, a claim of economic espionage may also be brought. Therefore, upon the passing of the Prevention Act, the United States may sue foreign sovereigns for acts of economic espionage committed on the behalf or at the request of a foreign sovereign.

In addition to having jurisdiction over a foreign sovereign for the act of economic espionage, the United States shall successfully overcome a challenge to standing. The International Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2015, which has been proposed by Congress, specifically makes it illegal for a foreign sovereign to commit an act of economic espionage against the United States. If the Prevention Act passes, and is signed into legislation, foreign sovereigns will become responsible for the acts of their agents and all those working on their behalf in an attempt to steal the trade secrets of United States businesses or government entities.

While opening the doors to such a policy may seem unwise, it will likely benefit the United States in the long run. Multiple countries hack into the electronic servers of United States’ businesses and government agencies on a daily basis. In fact, China alone is able to steal billions from United States businesses each year. The foreign sovereigns then use this information against the United States by arming its own state-owned businesses with the stolen secrets. This allows the foreign sovereign to get ahead of U.S. companies in the global market place. As a result, United States businesses not only lose money in the short-term, immediately after the trade secrets are stolen, they continue to lose money in the long-term as their competitors use stolen secrets to compete against them.

Conclusion

Where cybercrime and acts of economic espionage are increasingly prevalent in today’s society, foreign sovereigns should not be immune from liability for such acts. The proposed International Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2015 will extend liability for acts of economic espionage to foreign sovereigns as entities. Further, courts rightfully have jurisdiction over these foreign entities under the non-commercial tort exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. The act of economic espionage involves the tortious act of conversion, which is a non-commercial tort under 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(5). In overcoming these procedural issues, the United States should take action against foreign nations who commit economic espionage. Foreign sovereigns should not be able to hide behind a shield of immunity as they continue to steal secrets for their own economic gain.

Lauren Travers is a current 3L at Campbell Law School. She can be reached at l_travers0705