Life without parole for juveniles: How teenagers grow old in prison.

The law deems minors too young to vote, drink, or drive; however, a minor may be sentenced to life without parole for committing certain crimes. The issue of whether juveniles can be sentenced to life without parole is currently pending before the Supreme Court and there are strong proponents on both sides of this controversial issue. In 2005, the Court held in Roper v. Simmons that juveniles cannot face the death penalty, and in 2010 the Court further held that juveniles can no longer be sentenced to life without parole for non-homicide offenses. (Graham v. Florida) Opponents of such sentencing are now calling for the Court to extend its holding in Roper and Graham to homicide cases involving juveniles.

Attorney Simone VanHolten-Turnbull, Director of the Juvenile Division of the Territorial Public Defenders of the Virgin Islands stated, “There is no hard and fast rule in determining juvenile sentencing.” She went on to say that, “Juveniles under the age of 14 cannot and should not be sentenced to life without parole because they do not have the mental capacity of adults.” Many would agree with VanHolten-Turnbull and the Supreme Court will settle the issue in the upcoming months.

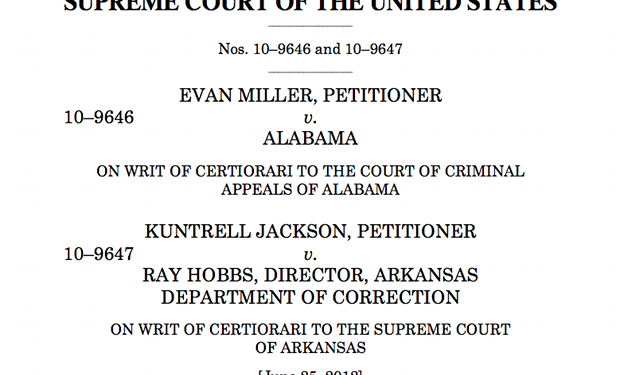

Jackson v. Hobbs is the matter currently pending before the Supreme Court involving a 14-year old boy that was sentenced to life without parole for a felony murder conviction. Kuntrell Jackson was a minor involved in an incident that began as a store robbery but quickly turned into a homicide. Although Jackson did not pull the trigger that ended the victim’s life, he was tried as an adult under a felony murder theory, as an accomplice to the murder, and was given a sentence of life without parole. There are currently over 25 filings for this case including a number of amicus briefs for and against juveniles facing life without parole.

One such brief was filed by the ABA in support of Jackson, finding that life without parole for juveniles constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. In its brief, the ABA stated that the same characteristics and differences between children and adults that were used to uphold Roper and Graham should be extended to the current case and that no juveniles should be sentenced to life without parole regardless of the type of conviction. In prior cases, the Court concluded that juveniles were less morally culpable and had a greater capacity for rehabilitation than adults. The ABA further stated that the standard theories of justice are not served by sentencing juveniles to life without parole and neither public safety nor penal objectives would be compromised by allowing the chance for parole.

Jackson’s attorney does not propose a moratorium on juvenile life sentences; rather that the opportunity for parole should be given to juveniles no matter what. Scientists’ have found that minors have incomplete brain development and mandatory sentences of life without parole rob juveniles of a chance to change their ways.

The controversy becomes muddled further when making distinctions based on a juvenile’s age. VanHolten-Turnbull would propose allowing life without parole sentencing for juveniles 16 years and older, only if the courts factored in the juvenile’s mental capacity, background, and education. She was certain that 14-year olds cannot serve life without parole sentences and that 16-year olds may serve life without parole sentences, but that still leaves a question as to what should happen to 15-year old juveniles. Proponents of the sentencing would dismiss the distinctions by allowing these sentences for all juveniles who are convicted of homicides.

Although proponents of this harsh sentence agree that minors are less culpable and more susceptible to external factors such as peer pressure, they believe that heinous acts (such as homicides) call for sentences which require punishment to the full extent of the law regardless of age or background. Many victims and families affected by juvenile violence argue that creating an exception for minors in mandatory sentencing would rob victims of their rights, claiming that minors know right from wrong and have the mental capacity to make appropriate decisions.

However, the law has historically created exceptions for minors. For example, minors are not allowed to enter into contracts, and labor laws prevent minors from working until they reach an appropriate age. These issues are compounded by the fact that juveniles are a completely different class under the law and they may require different governing principles. In addition, with the advancement of psychological studies, many juvenile attorneys are using scientific research to highlight differences between adolescents and adults that affect learning and culpability. Like any controversial issue, there is no standard as to what is appropriate.

In the case at issue, the court may decide to bar mandatory life without parole sentences for minors younger than 18-years old, may find a younger age in which to prevent defendants from being sentenced to life without parole or may narrow this particular ruling to felony murder cases in which a minor was involved. Many will be affected by their ruling and the question on what factors should play a role in determining sentencing will still hang in the balance. How will this ruling affect the criminal justice system and will it open the door for many other factors to be weighed in determining appropriate sentencing? With over 38 states imposing mandatory life sentences without parole for murder convictions, regardless of age or background, the Court has ample ability to potentially reverse the fortunes of many incarcerated teens or set factors that must be considered for future convictions.