Mugshots & the Degradation of the Presumption of Innocence

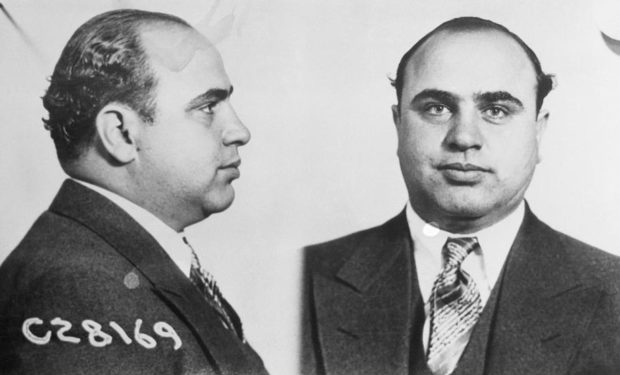

What do Johnny Cash, Bill Gates, Al Capone, and Martin Luther King Jr. all have in common? Mugshots. All of these history-defining individuals, for one reason or another, had interactions with the law. However, despite these figures gaining notoriety in spite of their mugshots, for many individuals, this is not the case. In fact, it is quite the opposite.

An Overview

A mugshot is a photograph taken by a law enforcement agency upon an individual’s arrest to be used in the identification of an alleged perpetrator of a crime or to help locate a fugitive of the law. The modern mugshot technique used today originated in France in the late 1800s. The purpose of a mugshot makes sense: just as we fingerprint an individual to have a record to match particular prints to a suspect, having a face to put to a record is very useful for identification purposes. Furthermore, the public has an interest in being aware of potential criminals in their area, as well as oversight over the criminal intake process of the government.

So, what is the issue? The issue lies in the unintended consequence of the reason and purpose of the mugshot itself. A mugshot is taken upon being charged or booked for an alleged criminal offense, but not all individuals that are charged are convicted. You may claim that either (a) some of the individuals actually are guilty of the crime or (b) were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time and the justice system will sort the issue out – so, what? If we are being honest with ourselves, I think it is fair to say that we are all guilty of intrinsically correlating a mugshot with guilt. However, this is not the standard that the American justice system is founded upon.

An Individual is Presumed Innocent (Unless There is a Mugshot)

Under the tenets of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, a suspect is presumed to be innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Read the comments on mugshots that have gone viral on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook and I can assure you, this legal standard is rarely applied. Depending on how one defines “criminal offense,” it has been estimated that between 70 and 100 million Americans have criminal records, though this estimate is likely on the low side. That is 70 to 100 million people that presumptively have mugshots and are affected by this issue.

Further, humans are naturally judgmental creatures. We immediately and subconsciously create opinions about people based on our past experiences, internal biases, and influence by the media. Based on the circumstances of the mugshot, the innocence or guilt of an individual is often affected by the person’s attractiveness, race, gender, etc. This means that in a matter of seconds upon viewing a mugshot, the viewer has already determined the subject’s likelihood of guilt or innocence without hearing any factual background. This begs the question: are mugshots doing more harm than good? Has the purpose of the mugshot been perverted?

Mugshot Website and Freedom of the Press

To make matters more complicated, the issue is amplified by online mugshot websites. Generally, under copyright law in the United States, the individual or organization that takes a photograph owns the copyright to the photograph. For mugshots, this would mean that the law enforcement agency holds ownership rights to the photograph. In efforts to ensure public oversight, law enforcement agencies post these pictures on their websites. These online mugshot sites scour police department websites collecting and posting these public mugshots. Depending on the website’s policies, it will either require proof of expungement or dismissal of the charges and/or charge a removal fee to have the mugshot removed.

This means that long after an individual has settled the legal issue, their mugshot can still be found online. This has negative repercussions for individuals seeking employment, online dating, furthering education, housing, and any other avenue that may require an internet search of the individual. Because mugshots are often featured on multiple websites through different search engines (e.g., Google, Safari, etc.), an individual is at the mercy of these websites in complying with each of their policies to have their mugshot removed – a modern practice that has been called extortion. Interestingly, in 2013, Google took the side of some legislatures by actually changing its search algorithm so that mugshots would not show up highly in search results.

This removal fee practice had become so rampant that many state legislatures enacted laws that made it illegal for these websites to charge removal fees. The argument that these federal and state officials are making is that publishing a person’s mugshot before they are convicted of a crime (or continuing to keep it published after their record has been expunged) creates a lasting and unfair impression of them. The response from the media companies, aside from claiming a violation of the First Amendment, is that the criminal justice process is quintessentially public and upon being charged with a crime, the individual’s information is no longer private.

The argument that an individual simply does not have a privacy interest in their mugshot once it is entered into the criminal system does hold some merit. By committing a crime against the public, the public has an interest in being aware of wrongdoers among them. However, when a jury must be insulated from the media during high-profile criminal cases, it’s not so much protecting the defendant’s privacy interest as it is shielding the jury from bias created by the media. In this same way, an individual may not have a privacy interest in concealing his mugshot shot pre-conviction or expungement, but the individual does retain a Sixth Amendment right to be confronted by an impartial jury of his peers. Who are we fooling by pretending these mugshots don’t create at least some bias?

Despite the good intentions of these mugshot removal fee laws, they have often created a Catch-22 situation. The laws do not restrict the sites from publishing the mugshots, they simply make it illegal to charge for the removal of the mugshots. This has essentially removed a legal avenue for the subject of the mugshot to take to remove the photograph, i.e., the sole remedy sought in the first place, and still, the mugshot remains online. So, what can state legislatures do?

So, What Are Our Options?

The promulgation of the publishing of mugshots entails several competing interests. Some federal courts have held that an individual does have a privacy interest in preventing the disclosure of their mugshots to the public because of their containing sensitive and potentially humiliating information.[1]

While other courts have historically held that despite the individual’s privacy interest, the public interest in ensuring “the Government’s activities be opened to the sharp eye of public scrutiny” outweighs the individual’s interest. Despite this split within the federal courts, state courts have tried several different approaches.

Starting in 2013, several states began enacting legislation that prohibited commercial sites from charging fees to remove mugshots from online sites. For example, Texas made it unlawful for a business to “charge a fee to remove, correct, or modify incomplete or inaccurate information” as well as publishing any criminal information if the business has notice of expungement. Illinois enacted a statute that forbids law enforcement agencies from publishing mugshots “on its social networking website in connection with civil offenses, petty offenses, business offenses, Class C misdemeanors, and Class B misdemeanors.” North Carolina has not enacted such legislation but a compilation of mugshot laws can be found here.

Despite the mugshot’s original purpose being taken advantage of for financial gain, they are a key part of the administrative process for law enforcement agencies and are unlikely to go away. Some have suggested that law enforcement agencies should flex their legal ownership rights and require mugshot publishing companies to cease and desist their publication. This approach, if constitutional, would present a huge burden on police departments in scouring the myriad of websites searching for photos that belong to their department. Other approaches outside of the legal avenue have also been taken by private companies such as MasterCard, American Express, and Discover after they reportedly cut ties with mugshot sites, removing a method of their funding.

And That’s a Wrap

The importance of the mugshot cannot be understated. It is a vital informational tool for both law enforcement agencies and the public. Though they have been perverted for financial profit, this is no reason to dismiss them all together. A more reasonable approach seems to be keeping the mugshot private until a final verdict is reached. Upon a finding of guilt, law enforcement agencies can retroactively publish the photographs. Furthermore, the public might agree with a proposal to limit the types of crimes that require the publication of a mugshot.

On the other hand, maybe the issue does not lie in the media’s proliferation of these photographs, nor in their categorization of public or private. Maybe this is simply a part of a much larger societal issue. Maybe the issue is society’s kneejerk reflex to assume the worst in others. Maybe we should ask ourselves: how much about someone can we really know from a brief snapshot in time? Regardless of the veracity of the allegations, who are we to judge another from their worst moments without hearing the merits of their case? Is it fair to hold this moment against an individual, like a modern-day scarlet letter, after they have served their time or been exonerated? Maybe the real issue is not about the photograph but about a need for society to take a look at itself in the mirror.

[1] For an interesting discussion on the federal implications of mugshots and the Freedom of Information Act, see here.