For-Profit Law Schools: Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution?

Note from the Editors: Recently, the Campbell Law Observer hosted a write-on competition to recruit new staff writers. Each student was to discuss the impact of for-profit law schools on the legal academy and the legal profession. Below, you will find the article that received the highest score from the editorial board. Next week, we will publish another student’s write-on prompt in an attempt to display two perspectives.

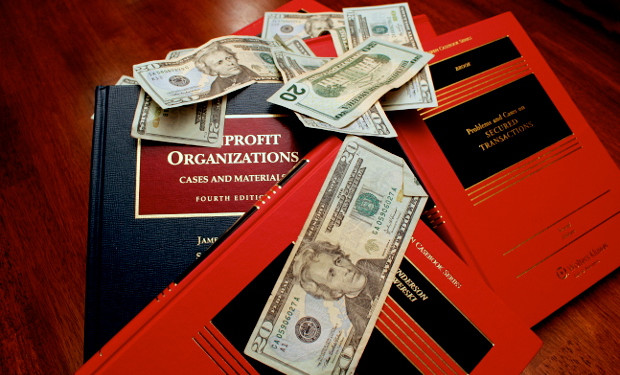

An important choice must be made by those pursuing a career in the legal system, and that same choice will continue to be made for generations to come: where to begin the journey. The process of applying to law school is an undertaking which cannot be taken lightly. Prospective students will examine the U.S. News & World Report rankings, pour over the ABA statistics on tuition and bar passage rate, and methodically read each and every page of brochures from schools under their consideration.

The path is one filled with a variety of choices along the way; however, not all choices are created equally. Whether it is the applicant or the school, there are certain defining features one is looking for in the other. The reality of the situation is that while schools have a limited number for enrollment, this number is still far below the number of prospective applicants each and every year. It can be said that law school is not a necessity, but rather a luxury for those seeking to further their education beyond an undergraduate degree. Most certainly anyone claiming law school to be a luxury has not had the “luxury” of standing up in class for an hour reciting the finer points of chicken. [ref] 1. See, Frigaliment Importing Co. v. B.N.S. Int’l Sales Corp., 190 F. Supp. 116 (S.D.N.Y. 1960). [/ref]

Part of the solution or part of the problem?

While the majority of law students will not attend a big-name school, a potential alternative that may be considered are “for-profit” law schools, a fairly recent addition to the legal academy.

The idea of a “for-profit” law school may sound somewhat contradictory to those seeking a career in the legal profession. Law firms pride themselves on their pro bono work, and state bar associations have guidelines, such as Rule 6.1 of the North Carolina State Bar Rules of Professional Conduct, that place an emphasis on aspiring “to render at least (50) hours of pro bono publico legal services per year.” Of course, this is all while working in a profession where, if the fees are right, six minutes of work performed could net more income than six hours of work by a day laborer. Finding a way to make money while providing a service is not a new concept to the legal profession.

So the question becomes – how will these schools affect the legal academy, and profession as a whole, and will that affect be any different than other law schools?

There is no shortage of law school graduates – an estimated 45,000 students graduate each and every year. For-profits have attained accreditation with the ABA, just as well-known public and private law schools have. Surely if the ABA thought an increasing number of graduates flooding the job market was an issue it would put a stop to the number of schools opening up, right? If only it were that simple.

The argument against for-profits is a fairly straightforward one to make. While rankings are not everything, they are something. It should be noted that for-profits consistently fail to achieve a ranking from the venerable U.S. News & World Report. It should also be noted that tuition costs at for-profit schools can be quite high considering the lower stature among the legal community. In a recent study on which law schools produce the most indebtedness for their graduates in 2011, Phoenix School of Law, a recently accredited for-profit, ranked fifth.

Legal blogs love to deride the legal education system for its continuing to increase enrollments and the ABA’s continued accreditation of law schools. It is catnip and assured page views. There is some truth to the overall dilution argument, otherwise there would not be the situation of graduates from two years ago competing for jobs with current graduates. However, for-profits are potentially easy scapegoats because of the tidy category they fit in.

But is the specter of not being ranked while paying a large amount of money in tuition specific to only for-profits? The answer is a clear “No” and makes the argument for for-profits a little easier. The aforementioned study showed that four of the “top” ten debt-producing schools are unranked (including Phoenix) and only three were even in the top 100. Tuition costs continue to increase at a rate much higher than inflation, while there has been a decrease in enrollment the last two years. Prospective students are beginning to take notice and decide against attending law school, at for-profits or otherwise.

Despite these declining numbers, there is still a consistent number of applicants who want to attend law school. Prospective students may dream big, seeing themselves as the next Tom Cruise, telling Col. Jessup that they want “the truth,” or receiving an offer to join “The Firm.” It should be noted, however, that both times Tom Cruise was Tom Cruise, Esq. he was a Harvard Law man through and through. This is simply not possible for a vast majority of applicants who must rely on lower-tier institutions if they wish to earn a law degree. This is where for-profits can provide an opportunity that may not be possible otherwise.

While the problem of dilution, if one must call it that, is felt by the legal academy and profession overall, in terms of for-profits it is likely a self-correcting one.

The school you go to will get you your first job, after that it is up to you.

Here’s the thing, for-profit schools in general, not just law schools, may have bitten off more than they can chew. Two years ago the U.S. Education Department began to focus on the issue of students in for-profit schools having a higher rate of defaulting on loan repayments. The government floated ideas such as restricting admissions growth or reducing federal funding for those schools whose numbers did not improve. This worry over the failure of for-profits to provide for their graduates has resulted in a two-year study, the “Harkin Report,” which was released by the government this past July. The Harkin Report primarily focuses on student loan repayment issues and how this correlates to the unrealized dreams of those who choose to go to school at for-profit institutions.

For-profits typically attract students who do not meet the more demanding requirements of top-tier schools. For instance, to compare two schools in North Carolina, Charlotte School of Law (a for-profit) reports a median LSAT of 149 and median GPA of 3.0, while the University of North Carolina School of Law (Ranked in the top 40) reports a median LSAT of 163 and median GPA of 3.5. Furthermore, the enrollees are typically those who are making a choice to leave a job and go back to school. Even if the economy were to make a vast improvement, there is no returning to the pre-2008 recession days where jobs were “falling out of the sky” for law school graduates. Also to consider is that for-profit law schools are a fairly new idea with many only recently becoming accredited. There is no vast network of alumni within the legal community like there is for schools that have been producing lawyers for decades.

Finding that first job upon graduation is a much more daunting task when the stars are simply not aligned in your favor.

Law schools in general will certainly suffer as potential applicants continue to become more reluctant to take on the three years of schooling and six-figure debt. Possible applicants will choose to keep the jobs they have rather than take the risk. Law school is hard work, both during school and after graduation, and many potential applicants are now weighing the risks.

A cycle could very likely begin where more-qualified applicants are less willing to take the risk that law school entails. As lesser-qualified applicants make up the ranks of the lower-tier schools it will invariably lead to lower bar passage rates and lower employment numbers. These are the numbers one could say truly matter. This will only discourage applicants even more, or worse, students who do enroll may be set up to fail. This is where the Harkin Report comes in: by demanding an increase in the quality of the education and a likely lowering of the tuition rates, for-profits will face the prospect of becoming unprofitable.

Certainly the problems affecting enrollment, repayment of loans, and the job market are not exclusive to for-profit schools, and not every student at a for-profit is set up to fail. While the students at the top of the class, just like students at higher-ranked schools, will be fine – it is the remaining 75% whose interests need to be kept in mind. Unfortunately for for-profit law schools the reality of the situation, as is the case in many fields, is that the last one in is typically the first one out.