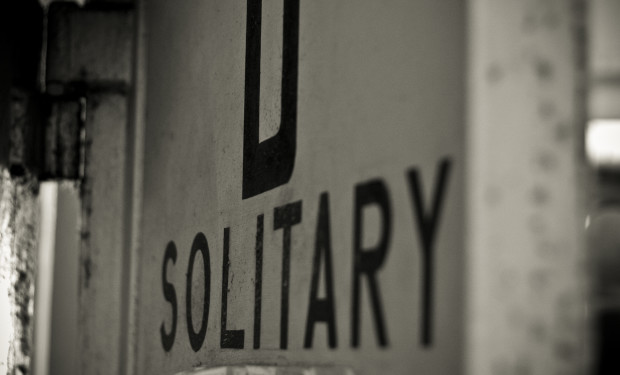

Re-thinking the use of solitary confinement

A federal appeals court decides that an inmate in solitary confinement may sue based on a procedural due process claim

A three-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit has ruled that an inmate placed in solitary confinement for the past twenty years is entitled to sue based on a violation of his due process rights. Lumumba Incumaa was placed in solitary confinement in a South Carolina prison and remained there for twenty years. Incumaa sued Department Director Robert Byars Jr. in his official capacity, and the district court judge dismissed the case, granting summary judgment to the South Carolina Department of Corrections. On appeal, the Fourth Circuit resurrected Incumaa’s claim on his right to procedural due process.

Incumma remained in solitary confinement despite the fact that he had not violated a single “prison rule” in twenty years

Lumumba Incumaa began serving a sentence of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole in a South Carolina prison in 1988. Incumaa is a member of the Nations of Gods and Earths, whose adherents are known as the “Five Percenters.” After his participation in a 1995 prison riot with other Five Percenters, he was placed in solitary confinement. Following the violent riot, the South Carolina Department of Corrections designated the Five Percenters as a Security Threat Group.

Inmates are placed in the maximum security unit if they have disciplinary infractions and are members of a “security threat group.” As a result of his affiliation with the Five Percenters and his involvement in the riot, Incumaa met both criteria for placement in solitary confinement. However, Incumma remained in solitary confinement despite the fact that he had not violated a single “prison rule” in twenty years.

Incumaa’s twenty years in solitary confinement “amounts to atypical and significant hardship in relation to the general population and implicates a liberty interest”

The Fourth Circuit stated in their opinion that Incumaa’s twenty years in solitary confinement “amounts to atypical and significant hardship in relation to the general population and implicates a liberty interest.” The Court went on to describe the conditions of the maximum security unit in which Incumaa was held. Inmates in this unit are rarely allowed to leave their cells, receive one hour of recreation about ten times a month, and are allowed a ten-minute shower three times a week. They also receive smaller food portions, are denied canteen privileges, educational and vocational opportunities, and may not receive mental health treatment.

Additionally, the Court held that there is a “triable dispute as to whether the Department’s process for determining which inmates are fit from release from security detention meets the minimum requirements of procedural due process.” Currently, the South Carolina Department of Corrections regulations require a designated committee to review each inmate’s candidacy for release from solitary confinement every thirty days.

Here, the Fourth Circuit ruled that Incumaa’s suit presents a question that is to be decided by determining if an inmate’s procedural due process rights have been violated in deciding if they are to remain in solitary confinement. Procedural due process is a principle derived from the Constitution, which necessitates that a person must be given notice and the opportunity to be heard when the state and federal government acts in such a way that denies a citizen of life, liberty, or property interest.

The court followed a two-step process in its procedural due process analysis. First, the court is to determine whether Incumma has a protectable liberty interest in avoiding solitary confinement. Second, the court is to evaluate whether the South Carolina Department of Corrections failed to afford Incumaa minimally adequate process to protect that liberty interest.

The Court notes that a person’s right to liberty does not “entirely disappear” when they are incarcerated

Liberty interests are rights that the Due Process clauses of the state and federal constitutions confer on an individual. Here, the Court notes that a person’s right to liberty does not “entirely disappear” when they are incarcerated. In Sandin v. Connor, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that prisoners have a liberty interest in avoiding confinement conditions that impose “atypical and significant hardship on the inmate in relation to the ordinary incidents of prison life.” The Supreme Court states that this is a case-by-case, factual determination.

The Fourth Circuit also addressed whether the Department’s review of ongoing placement in solitary confinement satisfies procedural due process standards. Once again, due process requirements are flexible in a prison setting and procedural protections are to be determined, as a particular situation requires.

Ultimately, the panel held Incumma had demonstrated a liberty interest in avoiding solitary confinement and the Department has not proven that it provided Incumaa meaningful review of his confinement.

Kennedy suggests that there is a growing awareness about the negative effects of solitary confinement

The Fourth Circuit opinion was issued shortly after Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy reflected on solitary confinement in Davis v. Ayala. Kennedy’s concurrence stated a death row inmate has spent most of his twenty-five years in prison in solitary confinement and this “exacts a terrible price.” Kennedy went on to say that “prisoners are shut away- out of sight, out of mind.”

Kennedy suggests that there is a growing awareness about the negative effects of solitary confinement. He cites a case about a teenager, Kalief Browder, who spent three years in solitary confinement for allegedly stealing a backpack. Browder committed suicide after being released from prison. Criminologists and psychologists have found correlations between solitary confinement and self-harm among inmates, as well as, solitary confinement and rates of mental illness in prisons.

Justice Kennedy appears to formulate a call to action as he predicts that the judiciary may be required in the proper case to “determine whether workable alternative systems for long-term confinement exist, and if so, whether a correctional system should be required to adopt them.”

The judiciary is not the only arena in which reform may take place. States such as Mississippi, Maine and Colorado have seriously examined who is being held in solitary confinement and the reasoning behind their confinement. Each of these states cut down their numbers by more than half, and even shut down some solitary confinement units all together.

Change in the use of solitary confinement appears to be approaching as it is becoming an important topic of conversation among the courts and the state systems.