Recognizing the face-value of facial recognition technology

As technological advances push facial recognition technology into everyday life, the law strains to protect consumer privacy interests.

Time to face the facts. Scrolling through Facebook one evening, you see some pictures from your friend’s recent beach trip. Next to the photos, you see a message from Facebook asking you – would you like to tag your friend? – of course, you decline to take Facebook up on its offer, and instead, you decide to just continue scrolling, not thinking it to be a big deal; but in reality, the technology behind the simple question is a huge deal.

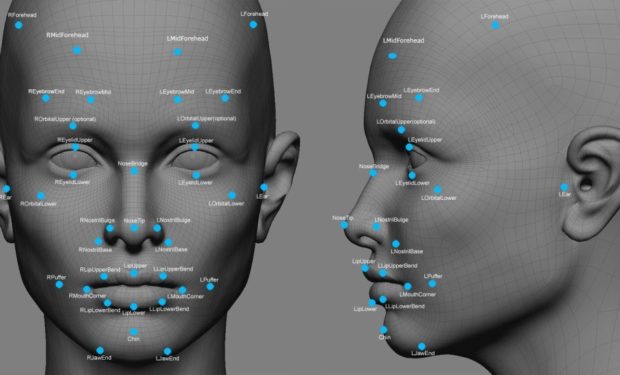

These tag suggestions come from Facebook’s decision to utilize facial recognition technology for the purpose of enhancing the social media experiences of users. Facial recognition technology uses information more broadly known as “biometric data,” which consists of both collecting and using geometric information gathered from the faces, irises, retinas, and fingerprints of individuals. This data is then applied to mathematical algorithms to create unique data profiles for individuals, known as templates.

Imagine a grid laying overtop of a face, dividing the face into several small regions. Each region is uniquely catalogued using very specific formulas. Essentially, each small region of the face would have a very specific line of code identifying that region. When each region is taken together, the entire face will have a template consisting of a very unique identification code compiled from the different dimensional regions.

During Facebook’s reveal of the iPhone X, Apple said that facial recognition technology would have a “one in one million” chance of being incorrect in making an identification. With such slim odds, along with efforts to refine the technology, one can only expect to see this technology become even more sophisticated over time.

Both the public sector and the private sector are utilizing biometric data to develop new, promising technologies that seem to offer everyone a greater future.

Biometric data analysis is an area of emerging significance not only in the world of business, but also in that of law enforcement. Both the public and private sectors are utilizing biometric data to develop new, promising technologies that seem to offer everyone a greater future.

While the societal benefits of biometric technology extend to improvements in health care, travel, marketing, production, and security, perhaps the most significant use of biometric data comes in its ability to solve rather complex and difficult problems in simple and intelligent ways.

James Robert Jones was convicted of murder in 1974, and was subsequently incarcerated in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Three years later, Jones escaped. For a long time, no one had any idea where Jones was hiding—that is, until facial recognition technology was utilized by U.S. Marshals.

Using biometric data analysis, Marshals were able to compare Jones’ old military ID to a database of Florida driver’s licenses, in which they discovered Jones had secured the license in 1981 under an alias. This breakthrough led Marshals to arrest Jones and bring him back to justice.

It was a simple solution to a complex problem. Jones had been hiding right in front of everyone, without anyone noticing. But once a biometric analysis was applied to a longstanding database, Jones’ arrest was made possible. The Marshals made the arrest at Jones’ place of employment with little expense.

Such technology almost seems too good to be true, partially because in its current state, it probably is. Thinking critically about the issues surrounding the integration of biometric data makes this point clear.

[I]t is of no surprise that many Americans are worried that biometric identification could effectively suppress First Amendment Free Speech rights.

The level of sophistication behind biometric data analysis has many people worried about their Constitutional rights—and for good reason. Many skeptics have called into question the accuracy of facial recognition software, referencing the fact that misidentifications could result in false positives for law enforcement.

Comparing the accuracy of facial recognition technology being utilized by Google, Facebook, and the Federal Bureau of Investigations, The Washington Post made some interesting findings. They discovered that Google, through its FaceNet algorithms, boasted 99.63% accuracy, Facebook’s DeepFace received 97.25% accuracy, and the FBI, which handles more difficult imagery, received only 85% accuracy.

In a society in which surveillance is growing, more and more streets are being occupied with the presence of cameras, and the notion of “privacy in public” is fading away. It is of no surprise that many Americans are worried that biometric identification could effectively suppress First Amendment Free Speech rights.

For example, social activists or protesters who might assemble in public now risk having their faces captured by cameras, and their identifications revealed through biometric analyses of existing databases. Individuals who wish to exercise their First Amendment rights may have to consider if such an exercise is worth the cost of suppressing their rights to privacy. For many, such a balancing of rights is improper.

[W]hat happens to the 2.75% of individuals who are incorrectly identified by Facebook’s DeepFace?

In a newly emerging trend, many individuals are taking to social media in the wake of major protests, posting images of protesters. This leads to their identities being revealed, so that employers may be encouraged to take private action against the individuals. With Facebook’s known “tag suggestions” feature, there is a great degree of probability that Facebook already knows the identities of individuals whose images are being captured at protests. This presents the question, what happens to the 2.75% of individuals who are incorrectly identified by Facebook’s DeepFace? Once an individual has been falsely stigmatized, it is hard to correct the mistake, whether the allegation is true or not.

With the new iPhone X’s facial recognition feature replacing the home button, many are unsure of the extent to which their personal security might be at risk, and ultimately breached. Many Apple users keep their secured data, such as passwords, confidential email communications, and financial information within the depths of their iPhones. Many have argued that the iPhone X could be used to access the iPhone of a sleeping person – or a deceased person – inadvertently and without user permission.

Easy accessibility allows for opportunity for due process abuse. It does not require much imagination for one to come up with a scenario in which law enforcement personnel could gain access to the cell phone of an individual in custody. With biometric technology, there will no longer be a need to request for Apple to unlock a suspect’s individual’s phone, so long as some three-dimensional representation of that person’s face exists. With computer technology that specializes in facial reconstruction, unlocking an iPhone no longer seems to be a daunting task.

The Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) requires written and informed consent before companies can gather fingerprints, facial measurements, or other biometric data.

Currently, there are no federal laws on the books concerning biometric privacy; however, Illinois has become ground zero in the struggle for the legal recognition of biometric privacy rights. The Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) requires written and informed consent before companies can gather fingerprints, facial measurements, or other biometric data. On February 27, 2017, in a putative class-action lawsuit, Rivera v. Google, Inc., a federal district court in Chicago denied a motion to dismiss by Google, allowing the putative class to challenge Google’s collection of its biometric data and subsequent creation of templates using the data compiled from their faces under BIPA.

In another putative class-action lawsuit, Norberg v. Shutterfly, Inc., filed in the Northern District of Illinois, the court denied a motion to dismiss raised by the defendants, noting that the BIPA statute has not yet been interpreted, and seemingly welcoming arguments on the issues raised by the statute. In the Shutterfly case, putative class members alleged that Shutterfly compiled biometric information from photographs without the class-members’ consent.

The National Law Review reported that there are several instances in which district courts have refused to dismiss BIPA claims. These on-going biometric privacy lawsuits are seeking to clearly set forth the legal contours of facial recognition technology, especially as it relates to companies’ flexibility in gathering and using biometric information.

As these pending cases have yet to be resolved, two important messages are worthy of noting.

Illinois legislators considered an amendment in 2016 to exclude photographs from BIPA, but after seeing the outcry from privacy-rights activists, the measure was put on hold. As these pending cases have yet to be resolved, two important messages are worthy of noting. First, companies interested in utilizing biometric information should beware. Until the extent of liability for misuse can be determined, interested companies should be hesitant as they move forward. Second, legislators should take note of the fact that people are concerned about their privacy rights being infringed by corporations. Until legislators take action, people are left to vote with their dollars. With Facebook’s far-reaching influence into the lives of the people, however, such market behavior faces practical limitations.

At a March 22 hearing held by the U.S. House Oversight Committee, Alvaro Bedoya, executive director of the Georgetown Law Center on Privacy & Technology, discussed the intersection between facial recognition software and police body cameras, saying that it would “redefine the nature of public spaces.”

Quartz Media covered the event, claiming that the intersection of police body cameras and facial recognition technology would transform life into “a perpetual police line-up.” Just as a police officer can enter a license plate into a database to gather information on that car’s owner, officers using facial recognition enabled body cameras would be able to walk through a crowd and subsequently evaluate individuals, discerning whether they are wanted for criminal activity.

Both the public and private sector are using biometric information to make a difference in the world.

The health care market has a clear vision for the impact that biometric geometry can have on the individual. According to a 2014 patent filing by Google Inc., plans are already in the works for an intra-optical lens that would be able to transmit biometric data to the wearer. Such technology opens up the possibility of giving individuals with impaired vision the ability to see, by relying on the facial templates created through Google’s facial recognition technology.

For businesses, personalized advertisements are already being created, with biometric algorithms identifying a customer’s shopping preferences, emotions, and even previous shoplifters. This new technique is revolutionizing the way businesses market products and make sales, enabling businesses to optimize performance while allowing consumers to save time.

Some airports have begun experimenting with facial recognition technology as an alternative means to boarding. Instead of using a boarding pass and showing a passport to board a plane, the person’s face essentially becomes their passport.

Both the public and private sector are using biometric information to make a difference in the world. The public sector is already successfully utilizing biometric information to catch criminals, make identifications, and secure facilities. And the private sector is enhancing health care and commerce. But what about those looking to take advantage of facial recognition technology for nefarious purposes?

Some have posed the hypothetical scenario of an individual using biometric data to construct a 3D mask of a person’s face in order to gain access to information secured by facial recognition technology. New forms of security demand new ways to breach that security. A new social media application called “FindFace” has taken Russia by storm. It purports to be able to match photos of individuals taken from crowds with their profiles on the FindFace app with 70% reliability, The Guardian reports. Essentially, a stranger could take your picture, and then locate your profile, gaining access to biographical information. In today’s connected world, that could be enough to gain a strong footing in another’s life. Apps like FindFace could open the door to potentially dangerous opportunities for abuse.

Biometric data-based technologies require intentional and considerate reflection before being opened up to the public.

While there are many legitimate concerns regarding the future of biometric information, it is likely going to become a part of people’s lives whether they want it or not. In a society that is becoming increasingly web-based, for individuals to abstain from online involvement is to effectively separate oneself from the world at large.

Biometric data-based technologies require intentional and considerate reflection before being opened up to the public. The integration of innovative technologies is often viewed through the lens of efficiency and practicality, when it may be more beneficial for individuals to consider the moral and ethical implications associated with emerging technologies.

The issue of facial recognition technology and biometrics needs to be taken to the legislatures. Individuals should approach the topic without a fear of change, but with an open mind. The landscape surrounding biometrics should not remain in the shadows, or resemble a wild west of virtual lawlessness. Instead, it should exist more as an invitation for discussion, debate, and discovery. Transparency invites trust.

The fact of the matter is that the future is not very distant. The ideas of yesterday are the realities of tomorrow. There is no way to stop it, but there is a way to familiarize yourself with it. So, get to know the technology, because chances are, it already knows you.