Stop the presses, put the safeties on

Legislators aiming to control the use of 3D printers to make guns may have overshot the mark.

The idea that an individual could have an unlimited supply of weapons and ammunition was formerly relegated to the realm of video games and science fiction movies. Today, however, the use of 3D printing has started to make this possibility seem far less remote by giving a person with the necessary means the ability to create multiple weapons in a very short time. 3D printers remain expensive, with the cheapest costing more than $1600, but that price is certain to decrease given time, while the quality of the product that they produce likely will only improve. The dangers that 3D printed weapons pose are real and ever-growing, a danger recognized by local, state, and the federal government. But the actions that have been taken by governmental bodies to curtail the threat may run afoul of the Constitution.

Lawmakers are concerned not only about potential victims of undetectable weapons but also about the individuals who use these weapons.

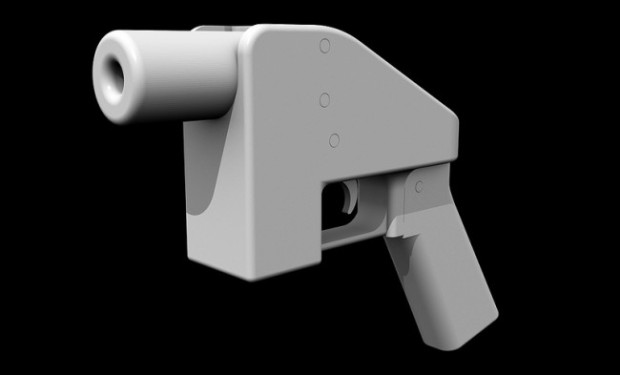

3D printers create products by spraying a series of thin layers of plastic on top of one another according to plans that are submitted to the printer. Because the products are made of plastic, weapons produced in this process will not be discovered when they pass through metal detectors.

Until recently, the law was undecided as to what would be the best response to individuals printing off guns through 3D printers. Now jurisdictions are beginning to weigh in on the subject. Philadelphia, for example, recently placed a ban on using 3D printers to print weapons, making it the first jurisdiction to do so. Although when the law was passed, city officials were not aware of any individuals who were using 3D printers to produce firearms, this preemptive measure was partially in response to the development of a type of firearm known as the “Lulz Liberator”, named after the printer on which it was first made. The threat posed by the Liberator is not a hypothetical one: recently, a journalist demonstrated the ease with which these weapons may pass through security undetected by smuggling a Liberator into a press conference being held by Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Congress has also begun to respond to the practice of using 3D printers to make guns. On December 9, 2013, Congress voted to extend the Undetectable Firearms Act for an additional ten years, and the bill was signed by President Barack Obama later that day. The Act forbids manufacturing, selling, or possessing weapons that will not trigger metal detectors or X-ray machines. The law requires that plastic guns have a metal pin affixed to them that will set off metal detectors during the screening process. This pin, however, is removed easily by the user.

Congress did not adopt the proposed addendums to the bill that New York Senator Chuck Schumer had advocated, which would have made it so that gun manufacturers would be required to include metal components in their designs that cannot be removed by users. Through the use of 3D printing, no safeguards are currently in place to ensure that the weapons printed are legal.

Lawmakers’ concerns about 3D printed guns are not just for the well-being of potential victims of undetectable weapons, but also for those individuals who use these weapons. The plastic that 3D printed guns are made of cannot long withstand the stress that is put upon the components from continued firings, soon causing the weapon to behave in dangerously unpredictable ways. In some cases, after only a few shots have been fired by the Liberator, the barrel has exploded, and in other instances the gun has misfired.

The Supreme Court has definitively stated that the right to bear arms is an individual right, not one exclusive to the military.

How the Supreme Court of the United States likely would rule on a challenge to laws of the kind adopted by Philadelphia remains an open question. In the 2008 case of District of Columbiav. Heller, the Court dealt with a regulation (pdf) that the District of Columbia had passed regarding handgun use and ownership. The District of Columbia allowed its citizens to keep handguns, but the city required that the weapons be disassembled at all times and kept in a locked container.

In its ruling, the Supreme Court struck down that ordinance and definitively stated that the right to bear arms is an individual right rather than a right that is held collectively and only able to be exercised in the context of the military. The Court in Heller specifically gave the go-ahead for individuals to keep handguns because this traditionally has been the preferred firearm kept by the American people for self-defense.

The guns made by 3D printers fit the category of “handguns,” which Heller said citizens were allowed to keep.

The Heller case was distinguished by the Court from the case of United States v. Miller, which preceded it by almost seventy years. In Miller, the Supreme Court had placed its support behind gun control. In Miller, the suspect was arrested and charged with transporting an unregistered, sawed-off shotgun across state lines. The suspect challenged his indictment by asserting that the Second Amendment protected his right to own the weapon. Miller’s weapon fell into a category of weapon that the Government had an interest in regulating; therefore, the Government was allowed to confiscate the weapon and deny him the right to own it. The Court in ruling on the Heller case found the two cases to be different from one another because the Miller ruling focused on the type of weapon that was owned by the suspect, while in the Heller case the suspect was in possession of a lawful firearm.

In ruling on a challenge to Philadelphia’s new ordinance banning 3D printed guns, the Court likely would follow the precedent set by Heller. The principle of supporting gun ownership established in the Heller case applies to 3D printed guns: the weapons produced by 3D printers fit the category of “handguns,” which Heller said citizens were allowed to keep. As opposed to the Heller case, where the District of Columbia effectively banned handguns by requiring that they be stored in a way that rendered them inoperable, Philadelphia did not ban handguns in a roundabout way; instead, guns that were produced by 3D printers were banned by the legislature outright.

While the weapons that are produced by 3D printers are handguns, they may also be classified under a particular category of weapon that could be subject to regulation just like sawed-off shotguns under Miller. Like sawed-off shotguns, which are highly dangerous because they are much easier to conceal than standard shotguns, 3D printed guns can be dangerous because they are plastic and are undetectable by a metal detector. As the Miller case established and the Heller case later affirmed, while individuals have the right to keep and bear arms, this right is not without limits; a person cannot keep and bear any type of arms whatsoever just because he or she desires to have them.

A person does not have an unlimited right to publicize any information merely because he or she wants to.

Recently, the State Department forced the organization that produced the Liberator, Defense Distributed, to remove the digital schematics that detail how to create the weapon from the internet. While Defense Distributed complied with the demand, those who supported the dissemination of the information denounced this action as a violation of the First Amendment. But does this actually violate the First Amendment? Just as individuals do not have a right to possess any variety of weapons that they desire, they do not have an unlimited right to publicize any information merely because they want to. For example, in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit case of Rice v. Paladin, it was established that if the Government perceives there to be a threat to public safety caused by a person’s speech, then the government is justified in curtailing the speech.

The Government, however, must demonstrate a connection between the speech and the potential harm that the governmental action is aimed at preventing. In the case of 3D printed weapons, the speech that is being suppressed is not directly connected to harm. The instructions that Defense Distributed released did not include any instruction that the users were to take the information and use the weapons produced by the process to inflict violent harm on people. One exception to the government’s ability to restrict speech that it perceives to be harmful is if the speech has some sort of value, which can include literary, artistic, political, or scientific worth. An argument could be made that the production of a type of working firearm that is made entirely of plastic could be said to have scientific value because it could revolutionize the way firearms are produced.

Through the use of 3D printers, the nation stands on the edge of a brave new world in which firearms could be made available to anyone who wants them. The actions that have been taken by national and local governments in order to respond proactively rather than retroactively to this new technology are admirable. But lawmakers must strike a careful balance between acting in the name of public safety and infringing upon the rights of individuals. The recent actions by the city of Philadelphia could violate the Second Amendment, and the actions by the State Department may violate the First Amendment. These individual liberties have successfully endured 224 years’ worth of technological changes and for that reason the advent of 3D printing is not likely to be more than they can handle.