Supreme Court OK’s new lethal injection drug

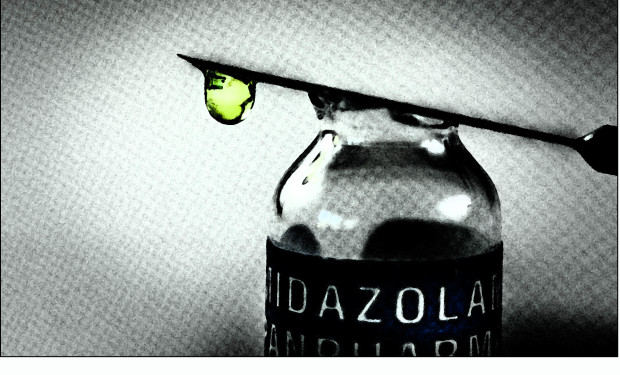

In a 5-4 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court holds that midazolam is a sufficient lethal injection substitute, and consequently does not violate the Eighth Amendment.

Only a few weeks after the State of Nebraska chose to abolish the death penalty, the United States Supreme Court has taken a controversial stand on death penalty procedures. The Court heard the Eighth Amendment case of Glossip v. Gross and decided by a 5-4 vote announced on June 29, 2015, that the drug midazolam may be a substitute for the previously used sodium thiopental in lethal injections.

Lockett’s botched execution and other incidents involving midazolam propelled the issue to the United States Supreme Court

The case was brought by a group of death-row inmates in Oklahoma who argued that the use of midazolam, a sedative, as used in Oklahoma’s lethal injection procedure, violated the Eighth Amendment. Counsel for the inmates argued that the use of the drug causes severe pain during the lethal injection which amounts to a violation of the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. The case stemmed from the controversy over the previously utilized drug for lethal injections, sodium thiopental. A mass shortage of sodium thiopental has seriously impacted states that have lethal injection as their principal form of capital punishment. Many pharmaceutical companies did not want to be associated with the executions, making the drug almost impossible to come by. This shortage has caused states to find alternative drugs for lethal injections. Oklahoma had to change over from sodium thiopental to using midazolam to cause unconsciousness during executions. Midazolam is then followed by a paralytic drug and then a drug that stops the heart.

Opponents have claimed that prisoners are subject to feeling agonizing pain, as evidenced by some botched executions in recent years. In Oklahoma just last year, death-row inmate Clayton Lockett was scheduled to be executed by lethal injection. During the execution, medical professionals could not locate a viable vein for injection of midazolam and the other two drugs. Eventually, the drugs were injected through an IV in Lockett’s groin, although the procedure was done incorrectly. This improper placement caused the chemicals to be injected into his tissue, and not his veins. Due to the improper placement of the IV, Lockett woke up halfway through the execution, mumbling inaudibly and attempting to get off of the table. The execution was halted after approximately twenty minutes due to these issues, but Lockett died minutes later. Lockett’s execution was one of the first ones in Oklahoma to use the drug, midazolam.

Opponents argued that the botched executions were not due to the drug itself, but from it being improperly administered

Lockett’s botched execution and other incidents involving midazolam propelled the issue to the United States Supreme Court. A lawyer for the inmates, Dale Baich, stated “Midazolam, the first drug in the three-drug formula used by Oklahoma, is not capable of producing the necessary, deep anesthesia to insure that a prisoner will not experience severe pain, needless suffering and a lingering death during the lethal injection process.”

On the other hand, fifteen states, led by Oklahoma, argued that midazolam is an appropriate drug for sedation during the procedure if given in very high doses. They argued that the botched executions were not due to the drug itself, but from it being improperly administered. Patrick Wyrick, the Solicitor General of Oklahoma, stated that the state has improved its procedures since the execution of Clayton Lockett and that the current procedures “do not present a substantial risk of severe pain and cannot be considered cruel.” In Baze v. Rees, which was decided in 2008, the Court found Kentucky’s lethal injection procedures involving the drug sodium thiopental to be constitutional punishment which did not violate the Eighth Amendment. The Court stated in that opinion that the purpose of the first drug (the sedative) was to prevent the pain and suffering of the combination of the two other drugs. Accordingly, the new problems created from the introduction of the drug midazolam needed to be addressed by the high Court.

The Court consequently held 5-4 that the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment had not been violated

Oral arguments were given by both sides on April 29, 2015, with counsel for the death-row inmates going first. During the oral arguments, the justices asked many questions and the Court also appeared to be deeply divided among ideological lines. The decision was announced at the end of the Court’s term with the Court ultimately holding in favor of the states. The Court consequently held 5-4 that the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment had not been violated.

Writing the majority opinion, Justice Samuel Alito said that the death-row inmates failed to present an alternative method that was less painful than midazolam. Justice Alito was joined by Justice Antonin Scalia, Justice Clarence Thomas, Justice Anthony Kennedy, and Chief Justice John Roberts. The majority opinion went on to state that lethal injection as a whole was constitutional, and that the Eighth Amendment did not require that executions be free of any chance of pain. Justice Alito elaborated, “[a]fter all, while most humans wish to die a painless death, many do not have that good fortune. Holding that the Eighth Amendment demands the elimination of essentially all risk of pain would effectively outlaw the death penalty altogether.” The Court ultimately held that the death-row inmates had failed to propose an alternative that had less risk of pain for death-row inmates.

One of the most significant takeaways from the dissent was the clear condemnation of the use of the death penalty

There were two dissents from the majority opinion, with one being written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor who was joined by Justice Elena Kagan and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The principal dissent noted that inmates executed under the current procedures were “exposed to what may well be the chemical equivalent of being burned at the stake.”

The other dissent was written by Justice Stephen Breyer who was joined by Justice Ginsburg. One of the most significant takeaways from the dissent was the clear condemnation of the use of the death penalty. Justice Breyer wrote that the debate over the death penalty needs to be re-examined for reasons of unreliability and because of executed inmates that are later found to be innocent of the crime they were convicted of. He then cited numerous studies on the effects of solitary confinement, accounts of inmates who were exonerated of the crime after they were executed, and the effects that race, geography, and skill of the inmate’s counsel have on who gets the death penalty in the first place. Justice Breyer finally then suggested that the death penalty may very well violate the Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. In response, Justice Scalia wrote a colorful concurrence stating, “Even accepting Justice Breyer’s rewriting of the Eighth Amendment, his argument is full of internal contradictions and (it must be said) gobbledy-gook.”

The various opinions on the Court reflect the controversial debate over the Court’s role on the subject of the death penalty. Although executions will undoubtedly continue to take place in some states with the announced decision in this case, the future of the death penalty still remains to be unknown.