Supreme Court Opens October 2012 Term with a Bang: Affirmative Action in College Admissions

The Supreme Court of the United States has wrestled with the reach of the Equal Protection clause since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. Courts across the country have considered the application of the clause to instances of age, sex, and race discrimination, and circumstances triggering the clause have ranged from voting rights to segregation on railroad cars. In just over a month, the Supreme Court will analyze the clause yet again, this time applying it to affirmative action in university admission policies, which may prove to be one of the most important cases decided in the new term.

Background of Case and The University of Texas Admission Policy

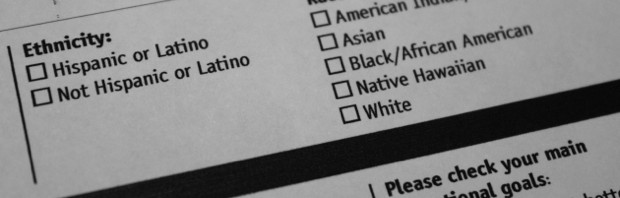

Undergraduate applicant Abigail Fisher brought the case, Fisher v. University of Texas, in 2008 when she was denied admission to the University. A young white woman from Sugar Land, Texas, Fisher would have been admitted automatically if she had finished in the top ten percent of her high school class under the state’s “Top Ten Percent Plan.” The plan was passed by the state legislature in 1997 after federal courts struck down an earlier admissions policy that took race into account. Although the plan resulted in an increase in minority student admission, the University revisited the Plan after the Supreme Court’s 2003 ruling in Grutter v. Bollinger, which held that public colleges and universities could take race into account in indistinct ways to increase minority undergraduate enrollment so long as a point system was not used.

The Court in Grutter held that while “racial diversity” is a valid goal in higher education, college leaders may only try to advance that goal if race is not the decisive factor by itself. Thus, officials at the University of Texas revised their admission plan in 2005. Under the new plan, the Top Ten Percent provisions remained applicable, but students falling short of the 10 percent threshold were considered based on talents, leadership qualities, family circumstances, and race. After Fisher did not make the cut in either group, she believed it was because of her race and filed suit against the University.

Procedural History of the Case

Fisher lost her original case in 2009 when United States District Court judge Sam Sparks found that the University policy met the standards laid out in Grutter v. Bollinger. A Fifth Circuit panel composed of three judges concurred with Sparks’ ruling in 2011. In his ruling, Judge Higginbotham stated that the “ever-increasing number of minorities gaining admission under this Top Ten Percent Law casts a shadow on the horizon to the otherwise-plain legality of the Grutter-like admissions program, the Law’s own legal footing aside.” The court held that race can be used in considering applicants for admission only if the process allows for consideration of each student applying for admission as an individual, and applicants of all races are entitled to the same kind of evaluation. The Court prohibited the use of racial stereotypes, and racial quotas for determining admissions and said the University may not award a fixed number of “bonus points” to minorities in calculating applicant indexes.

Finally, aside from admissions policies, the Court said the University could work toward its goal of a “critical mass in minority admissions” by expressing an increased variety of views in classroom discussions, preparing students to be professionals in “work and citizenship,” and in preparing students to engage actively in the nation’s civic life. The University promised to review its admissions plan every five years to ensure it is working to achieve its goals within constitutional bounds.

In September 2011, Fisher’s attorneys filed a petition seeking review from the Supreme Court, raising the issue of whether prior Supreme Court decisions on racial equality permit the University of Texas to use race in the selection of its incoming classes. The Court granted certiorari on February 21, 2012. Justice Elena Kagan has recused herself from the case. Although the recusal has not been explained by the Court, many suspect her recusal is due to Justice Kagan’s position as Solicitor General in the Department of Justice and her previous involvement in the case.

Public Opinion and the Effect of the Case

Prior to the Court’s decision to hear the case, the issue of affirmative action had briefly faded from the public eye. In fact, when Grutter was decided in 2003, allowing public colleges and universities to take account of race in admissions decisions, the majority said it expected the decision to last for 25 years. However, by agreeing to hear a case involving race-conscious admissions, the Court thrust affirmative action back into public and political discourse.

Many opponents of Fisher’s case were surprised and somewhat alarmed with the Court’s willingness to reconsider affirmative action in college admissions. “I think it’s ominous,” said Lee Bollinger, the president of Columbia University, who was also a defendant in the Grutter case, “It threatens to undo several decades of effort within higher education to build a more integrated and just and educationally enriched environment.” However, some supporters of Fisher’s case see this as an opportunity for the Court to take a decisive stance on affirmative action. “Any form of discrimination, whether it’s for or against, is wrong,” said Hans von Spakovsky, a legal fellow at the Heritage Foundation. He noted that his daughter is currently applying to college and said, “The idea that she might be discriminated against and not be admitted because of her race is incredible to me.”

Amicus briefs have been filed by several key actors in the political and educational world including the Texas Association of Scholars, the American Civil Rights Union, the Center for Individual Rights, and Teach for America. With eight Justices taking part, there is a chance the Court will be split, which would simply result in the Fifth Circuit Court decision being upheld. The outcome would be binding for Fisher and the University of Texas, but it would not set a precedent for any other case on the same issue. To reach a definite decision for or against the University’s admissions plan, it will take five votes among the eight participating Justices. If the Court overrules Grutter, it would likely end affirmative action in public colleges and universities across the United States. A one-hour hearing on the case will take place on October 10, but there is no set timetable for the Court to announce its decision.