The FCC has new net neutrality rules, because everyone loves toll roads

FCC Commissioner Tom Wheeler has proposed a new set of rules to protect the free and open internet.

Here is a rundown of internet-related news over the past week: Vladimir Putin accused the CIA of creating the internet in order to control the world; Aereo and the major networks battled over the future of television and cloud computing; Yahoo announced it will live stream a concert every day for a year; Microsoft announced a new online television-related project, taking a page from Netflix; the former director of the NSA admitted he had no idea what Pinterest was; millions of AOL email users were informed that their accounts may have been compromised; Comcast announced a structuring of its proposed takeover of Time Warner Cable to bring the inevitable behemoth’s reach to just under thirty percent of America. And that is just a smattering of the highest profile news.

But something else happened that immediately drew the ire of the collective World Wide Web: the FCC’s new net neutrality rules were revealed.

In hindsight, everyone should have known this was coming. From the moment the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit struck down a majority of the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”) Open Internet rules, it was just a matter of time. Since the moment the final rules were announced in 2010, key net neutrality supporters knew it was a “house of cards.” Better yet, the creator of the phrase “net neutrality” saw it coming before it even happened.

Mr. Wheeler knows his options and would not choose to move away from net neutrality to net discrimination on a whim.

So what is it that was so inevitable? The demise of net neutrality – the principle that Internet Service Providers (“ISPs”) must treat all web content and traffic equally – as a legitimate and viable principle in today’s political climate. The FCC, the very agency that has taken charge of protecting access to the internet by consumers and content creators alike, has finally succumbed to the pragmatic, political choice that net neutrality is just too hard. It is not for a lack of trying by FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler. He knows his options and would not choose to move away from net neutrality to net discrimination on a whim. Mr. Wheeler has a great deal of experience in the industry and in politics, but sometimes the easier path in the short term will make the path harder in the long term.

So what does Mr. Wheeler propose? In a manner of sorts, the dynamic net neutrality he initially said he favored following the D.C. Circuit’s ruling. Mr. Wheeler’s plan is to follow “the roadmap established by the Court as to how to enforce rules of the road that protect an Open Internet” and “to have enforceable rules by the end of the year.” The proposed rules will “establish that behavior harmful to consumers or competition by limiting the openness of the Internet will not be permitted.” Specifically, the proposal will include:

- That all ISPs must transparently disclose to their subscribers and users all relevant information as to the policies that govern their network;

- That no legal content may be blocked; and

- That ISPs may not act in a commercially unreasonable manner to harm the Internet, including favoring the traffic from an affiliated entity.

Particularly relative to the third point, Mr. Wheeler is proposing that “a high bar for what is ‘commercially reasonable’” be established for ISPs. That sounds great. But the proposal would also allow ISPs to charge content creators and distributors higher fees for better access and service beyond that commercially reasonable level. Certainly this would not create a slow lane, but it sure would create a fast lane. And it would do so in a manner completely contrary to net neutrality principles.

Defining what is “unreasonable” is going to take more than a few court cases.

To be fair, setting a minimal level of expectations could have a number of benefits. Offering more guidance not only provides ISPs with direction as to what level of service should be offered, but it also benefits the content creators by establishing the floor that their applications will need to meet.

However, there are also issues with establishing a baseline of quality. For instance, just what is that baseline expectation for ISPs? If you look at what the FCC considers to be “broadband” internet you will find a number (4Mbps down and 1Mbps up) that in reality is far below what is necessary in today’s world. Every law student learns to loathe the word “reasonable.” Non-lawyers also end up detesting the word when they are subject to a court’s definition of what is reasonable. And therein lies the issue with requiring that ISPs do not act “unreasonably”: defining what is unreasonable is going to take more than a few court cases. The FCC will, of course, seek commentary on how to define this reasonable expectation after the rules are officially announced on May 15, 2014. Comments will assuredly come from players on all sides of the issue; litigation, however, is driven by the word “reasonable.”

What’s more, the FCC has already tried the “reasonable” route. The 2010 Open Internet rules provided ISPs with the ability to treat internet traffic differently as long as it was for “reasonable network management.” Broadband networks in the United States are expensive to build out, and this has contributed to the slow pace of fiber development. Even so, this loophole was, of course, widely criticized by consumer interest groups. Moreover, relying on a stronger transparency rule—one of the very few aspects of the Open Internet rules upheld by the D.C. Circuit—as a disincentive to ISPs only adds to the potential for litigation after an ISP has somehow violated the rules. ISPs have already shown that they will gladly push the boundaries of what will be acceptable.

Mr. Wheeler is nothing if not pragmatic, and he undoubtedly has a lot on his plate.

The criticism of Mr. Wheeler’s proposed rules has been loud, emphatic, and bipartisan. North Carolina Republican Senate candidates, for example, all stated their opposition to the federal government enacting “barriers to make things fair” and that competition, rather than the government, should govern the speed of internet access. On the other side of the political aisle, outspoken Democratic Senator Al Franken wrote a letter to Mr. Wheeler asking him to reconsider his “misguided approach,” stating that it was “difficult to understand how it does not flatly contradict [the FCC’s] net neutrality rules.”

In response to the wide-ranging criticism, Mr. Wheeler penned a blog post asserting that he is a “strong believer in the importance of an Open Internet.” He posited that the FCC has two options following the D.C. Circuit’s ruling. One option is to try his approach, which will ensure that the internet “remain[s] like it is today, an open pathway” and will not “leave the market unprotected for multiple more years while lawyers for the biggest corporate players tie the FCC’s protections up in court.” The other option he discusses is the politically more-difficult measure of reclassifying broadband internet under common carrier status (Title II). This would effectively treat the internet as a utility but likely result “in additional years of litigation and delay.” In fact, Mr. Wheeler warns ISPs that if his proposal “turns out to be insufficient or if we observe anyone taking advantage of the rule, [he] won’t hesitate to use Title II.”

“If we observe anyone taking advantage of the rule, I won’t hesitate to use Title II.”

Consumers could rightly feel encouraged by Mr. Wheeler’s words. In addition to his warnings to ISPs, he makes note of the lack of competition in broadband service and gives reference to action being taken on the matter of competitive municipal broadband networks. Mr. Wheeler also wisely reminds the general public that this is a proposed rulemaking. Nothing is set in stone and nothing is off the table. Moreover, a number of tech companies support the dynamic approach to maintaining a free and open internet. And while the official comment period has not yet opened, the FCC has set up a special email address to invite comments from the public on new net neutrality rules.

But net neutrality is not a purely consumer access issue, and ultimately Mr. Wheeler’s proposal goes against the very grain of a free and open internet. Mr. Wheeler’s blog post largely focuses on the potential for degradation of consumer access to the internet. This focus is important, but allowing ISPs to charge higher prices for content creators to provide their internet-driven services to consumers makes degradation of a consumer’s internet speeds a moot point. Degradation goes both ways, and the consumer will feel it in the end. Moreover, services like Netflix, Hulu, and Spotify may seem like luxuries now, but content consumption will soon be completely online. Even the FCC is looking to further this “IP Transition.” Just like how the internet was not widely considered as a necessity twenty, maybe even ten, years ago, these and similar services will soon be necessary as well. Not to mention the fact that the current Information Age is driven completely by the internet. The road goes both ways, but the toll will be felt by all.

Mr. Wheeler’s short-term approach is likely a result of his taking a long, hard look at the FCC’s docket and wondering how he can accomplish everything that must be done in the next few years. There is the already-delayed spectrum auction in less than a year, the continual push to increase wireline and wireless broadband access across the nation, the Comcast-Time Warner Cable merger, and a Congressional plan to update the Communications Act. Maybe keeping the FCC’s focus on regulating the internet’s infrastructure is a good thing. In fact, there are vocal critics that say this is the only aspect of the internet that the FCC has the power to regulate, if at all – that the internet, especially net neutrality rules, is outside the bounds of the agency’s regulatory grant of power. Mr. Wheeler is nothing if not pragmatic, and he undoubtedly has a lot on his plate.

There have also been some interesting proposals on how to preserve the ideals ingrained in the internet since its inception.

There has been a lot of finger pointing as to whom is to blame for the demise of net neutrality: current FCC Chairman Wheeler, former FCC Chairman Genachowski, ISPs, lobbyists, President Obama, Congress. And the list goes on. But there have also been some interesting proposals on how to preserve the ideals ingrained in the internet since its inception, like one put forward by Columbia Law professor Tim Wu and research scholar Tejas Narechania. The pair argue that the entire view of the internet needs to be flipped on its head and that “FCC should selectively be able to apply more stringent, telecommunications-type regulations to certain aspects of an industry that tends to escape easy definition.”

“For about 80% of Americans their only choice for a high-capacity internet access connection is their local cable monopoly.”

Another possibility arises out of solving the very real lack of competition between ISPs. A way to increase competition, and presumably create a market that could actually hold ISPs accountable, would be municipal broadband. Susan Crawford, former advisor to President Obama and current Professor of Law at Cardozo School of Law, recently spoke to Vox.com and offered a convincing case for why there should be a public option. “For about 80% of Americans their only choice for a high-capacity internet access connection is their local cable monopoly,” she told Vox. But twenty States currently have laws on the books that prevent cities and towns from offering competing broadband networks. Statutes limiting municipal broadband, like those in North Carolina, mean that even when towns build out a fiber network, it can be used only for municipal—not consumer—purposes. Even so, this option to increase competition is not without merit. While still responding to the criticism of his net neutrality proposal, Mr. Wheeler announced in a speech on April 30 that he intends to exercise the FCC’s power and “preempt state laws that ban competition from community broadband.”

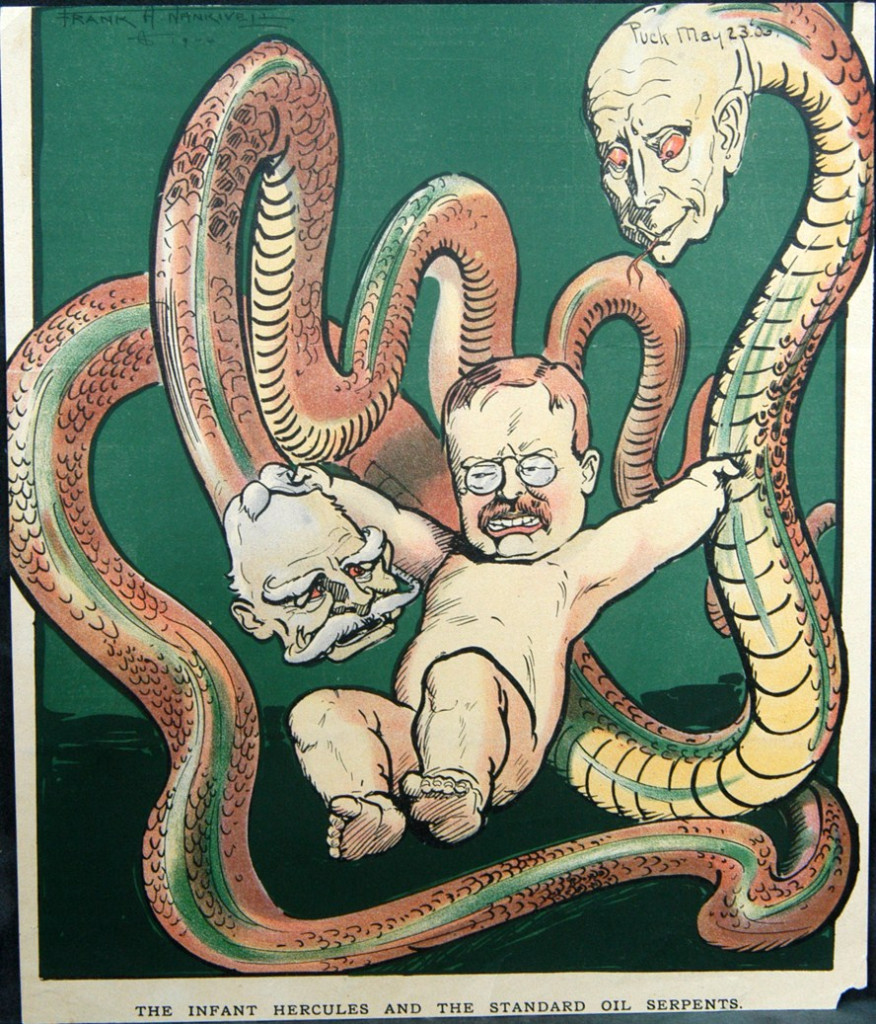

Perhaps what the internet really needs is a modern-day, trust-bustin’ Teddy Roosevelt. So maybe the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) should take over? If the FCC truly desires to focus on the short-term and direct its focus completely to the infrastructure side of the internet, then why not turn to the agency in charge of consumer protection? That is one very important side of the issue here – protecting consumers. In theory, the FTC could protect consumers’ online interests through current antitrust laws and its anti-deception regulatory authority.

Consumers will not pay the toll directly, but the toll-paying content distributors will eventually pass it down.

So in the end, what will the landscape look like if these proposed net neutrality rules are made final? Here is the likely chain of events that could occur under the new rules. ISPs will charge a content creator some sort of fee to deliver its content to consumers at a higher and faster quality. The content creator will do what it can to gain a leg up on its competition and eventually choose to pay the fee. (Note, the content creator is not paying for something that harms a competitor, but rather it gains its advantage when it can pay for something in which a competitor cannot.) That fee will then be passed down to the content creator’s users – the same users that pay increasing internet bills every month, despite average internet speeds ranking far behind a number of other countries.

And this does not take a stretch of the imagination—Netflix is the real-time test case. Very quickly after the D.C. Circuit’s decision, Netflix announced a deal with Comcast where it would essentially pay for better access to the pipes. Netflix made this move despite statements from Netflix’s CEO that he would take to the streets and rile up Netflix users against ISPs should they dare to violate net neutrality principles. But Netflix signed the deal it felt forced to make. Netflix then announced a forthcoming price hike just a few months later, in part to pay for its agreement with Comcast and soon-to-be others.

To sum it all up, the likeliest effect of the new net neutrality rules is twofold. First, content creators and distributors can and will be squeezed for a few extra dollars simply because they can be. For the internet titans of the world, this amount may be much more manageable than it would be for a fresh start-up scrounging for cash. But that does not mean it is any less offensive to a free and open internet. Second, consumers will pay the toll as well. They will not pay directly, but eventually the toll-paying content distributors will pass it down. Business as usual, right?