Voir Dire Vindication

A three-decade-old murder conviction is challenged on a potential Batson violation

Eighteen years ago, Timothy Tyrone Foster was sentenced to death after being found guilty of murder. In 1987, a jury in Georgia found that Foster had murdered 79-year-old Queen Madge White by strangling her in her home. Foster appealed the conviction, claiming that he has a mental disability. The appeal failed, and Foster remained on death row.

Foster, a black man, was ultimately convicted by a white jury

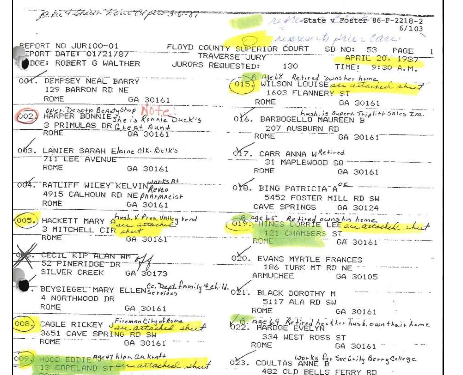

Nearly two decades later, new information came to light during a records request—when the jury was chosen for Foster’s trial, potential black jurors were highlighted with a green highlighter, with notations reading “B#1,” “B#2,” and “B#3.” Only four black potential jurors sat in the jury pool of forty-two people, and all four jurors were struck by the prosecution. Defense counsel for Foster objected at the time, and the court found that there was racial discrimination. The prosecution then gave forty reasons for the strikes, which the defense argued were “pretexual.” Persuaded by the prosecution’s argument, the court allowed the strikes.

Foster, a black man, was ultimately convicted by a white jury. Foster again appealed, this time on the basis that a Batson violation occurred during jury selection.

Similar to Foster’s trial, the prosecution struck the four black potential jurors during voir dire and assembled an all-white jury

Batson v. Kentucky, made it impermissible to strike jurors during jury selection (voir dire) on the basis of race. James Kirkland Batson, a black man, was accused and convicted of burglary and receiving stolen property. Similar to Foster’s trial, the prosecution struck the four black potential jurors during voir dire and assembled an all-white jury. Batson was found guilty.

The prosecution in Batson argued that they could strike anyone under a peremptory challenge, regardless of the reason. Batson appealed, claiming that his Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment rights to equal protection had been violated. The Supreme Court agreed with Batson, finding that racial discrimination during jury selection denies a defendant equal protection under the Constitution.

The U.S. Supreme Court will review Foster’s claim that his right to equal protection was violated when the prosecution excluded potential black jurors nearly thirty years ago. Because Foster went to trial after Batson was decided, although it was only a year later, the Supreme Court’s decision in Batson dictated how the prosecution in the Georgia court should have acted when choosing a jury for Foster.

If the Supreme Court finds enough evidence this coming fall … Foster will win his appeal and potentially escape death row

In order for Foster to win the appeal, he will have to show that the prosecution team purposefully intended to exclude blacks from the jury. The prosecution claims that the green highlights were innocent; two of the prosecutors claim they did not make the marks. However, the prosecution may have a difficult time denying that racial bias did not exist—in closing arguments; the prosecution team told the jury that the death penalty should be imposed on Foster to “deter other people out there in the projects.”

If the Supreme Court finds enough evidence this coming fall to conclude that the prosecutors did intend to remove blacks from the jury to give their case against Foster a better chance, Foster will win his appeal and potentially escape death row. So far, the Georgia state court and Georgia Supreme Court have sided with the prosecution.

Other recent appeals have raised the issue of discrimination during voir dire

Other recent appeals have raised the issue of discrimination during voir dire. In State v. Saintcalle, the Washington Supreme Court had to determine if purposeful discrimination during jury assembly was unlawful. The only black juror in the jury pool was removed via the prosecution’s peremptory challenge. The defendant, a black man, appealed his murder conviction, claiming a Batson violation had occurred. The Washington Supreme Court found that a violation did not occur because the juror admitted that she could not be impartial when judging the defendant, as she recently knew someone who had been murdered. The Court determined that the prosecution did not purposely remove her on account of race, but rather due to her inability to fairly determine the defendant’s guilt.

When choosing a jury, parties must also not discriminate on the basis of gender. In J.E.B. v. Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court found that it is impermissible to strike jurors on the basis of gender. The case came to the Court in 1994 on appeal after only females were selected for a jury in a trial against a man for paternity and child support. Potential male jurors were removed by the State via peremptory strike. The jury found for the mother.

The Fourth Circuit case of United States v. Lighty questioned if Maryland prosecution had purposely discriminated against women when striking jury members. The petitioners, Kenneth Jamal Lighty and James Everett Flood, III, referred to a 2010 case that highlighted the frequency of female potential jurors being stricken in capital cases. However, the Petitioners failed to provide enough facts from their own case that showed purposeful discrimination during jury selection, even though only a mere inference of discrimination need be established for a prima facie case.

[A]ny discrimination law based on sexual orientation is murky at this point

More recently, the Ninth Circuit has ruled that it is impermissible to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation when assembling a jury. Under Title VII, sexual orientation is not technically a protected class, but rather any sexual orientation based complaints fall under sex discrimination. Thus, any discrimination law based on sexual orientation is murky at this point.

Last year, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals found that parties are forbidden from discriminating against jurors on the basis of sexual orientation. The controversial case, SmithKline Beecham Corp. v. Abbott Laboratories, arose from questionable HIV drug pricing. One juror was stricken by an attorney for SmithKline Beecham when he mentioned that he had a male partner. On review, the Court determined that discriminating against jurors solely because of sexual orientation is “deplorable.”

As of now, discrimination based on sexual orientation during voir dire is forbidden in the 9th Circuit, but other courts could soon adopt the standard if a situation arises that questions it. Furthermore, if the U.S. Supreme Court finds in June that gay marriage is not to be left to the states, but rather is an issue of equal protection, discrimination in jury pools based on sexual orientation would likely be prohibited.

Essentially, attorneys must be careful to not let personal bias or beliefs rule when choosing a jury. A legitimate non-discriminatory reason must be provided for dismissing a juror if questioned, or the attorney risks losing the case. After all, Timothy Foster just might escape death row because of personal bias.