Parents are always looking to give their children an edge. Whether it is screaming from the sidelines during a soccer game or secretly building their kids’ Science Fair projects, parents want their kids to be viewed as the best.

Perhaps the greatest example of the drive to “find an edge” is the Mozart Effect. The phrase was first coined in a 1993 UC-Irvine study under the simple premise that if a child listens to classical music then the child will invariably be “smarter.” Unsurprisingly, this premise has been debunked (pdf) many times over. But that has not stopped many new parents from continuing to buy classical music albums for their newborns. Perhaps the thinking goes that, if anything, the music should still be useful at nap time.

Fisher-Price has engaged “in deceptive and unfair trade practice . . . in its sale and marketing of its Laugh & Learn apps, all of which are targeted to children as young as 6 months old.”

If classical music cannot get the job done, then maybe the latest and greatest technology—namely smartphones and tablets—can play a role in making a child “smarter” than other children? That is what a group of parents apparently thought when they downloaded apps marketed towards improving their beloved babies’ learning skills. Shockingly, the parents were disappointed with the results. The displeased parents, however, have found a voice in Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood (CCFC), a consumer advocacy group whose mission is “to support parents’ efforts to raise healthy families by limiting commercial access to children and ending the exploitive practice of child-targeted marketing.”

CCFC filed a complaint (pdf) with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) on August 7, 2013, requesting an investigation into two particular app-makers: Fisher-Price and Open Solutions. Within a week, Open Solutions changed its marketing practices and CCFC has since dropped the company from its complaint. Fisher-Price, however, has not changed its marketing of certain apps targeted towards babies, and the company’s senior director of children research was quoted by The Hill as stating that the company’s “toy development process begins with extensive research by our internal team of early childhood development experts to create appropriate toys for the ways children play, discover and grow.”

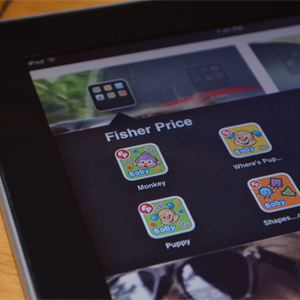

CCFC’s complaint against Fisher-Price specifically alleges that the company has engaged “in deceptive and unfair trade practice . . . in its sale and marketing of its Laugh & Learn apps, all of which are targeted to children as young as 6 months old.” An example of this allegedly unfair and deceptive marketing can be found in Fisher-Price’s Learning Letters Monkey app—one of the specific apps targeted by CCFC. The app is advertised by Fisher-Price as teaching babies through characters that “come to life.” And how does the app teach babies one might ask? The app “Teaches letters A-Z, numbers & counting 1-10, shapes and colors.” Certainly, the thinking must go, the babies poking and prodding an iPad screen will be “smarter” after using this app!

But what exactly is the motivation behind CCFC’s complaint? Reimbursing the supposedly-hoodwinked parents for the cost of a download is certainly not the motivating factor—the apps are free. CCFC, for its part, feels that “time with tablets and smart phones is actually the last thing babies need for optimal learning and development.”

Despite CCFC’s confident contention that Fisher-Price has satisfied the requisite elements to have committed unfair and deceptive trade practices, each element raises a number of questions.

The statutory support for CCFC’s unfair and deceptive trade practices claim can be found in Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act. CCFC’s complaint points to three elements that are considered when determining if there have indeed been deceptive acts by Fisher-Price: first, is there a misrepresentation likely to mislead a consumer; second, from the consumer’s perspective, were the consumers acting reasonably in the circumstances; and third, is the representation “material”? CCFC contends that all three elements are met, stating that “Fisher-Price has made material representations that are likely to mislead parents acting reasonably in the circumstances, to the detriment of the parents and their babies.”

Despite CCFC’s confident contention that Fisher-Price has satisfied the requisite elements to have committed unfair and deceptive trade practices, each element raises a number of questions. First, is an app description claiming to help babies learn really “likely to mislead” a parent? Second, is a parent “acting reasonably in the circumstances” when he or she places an iPad in an infant’s lap? And third, is the marketing message truly “material” in the sense that the parents who would download the apps would be doing so predominantly because of the promise to produce smarter babies?

Is it reasonable for parents to place a piece of technology in their baby’s hands and expect that baby to suddenly become smarter?

The strongest argument the consumer advocacy group can make concerns the first element. Fisher-Price has plainly made statements regarding its apparently deficient apps, and CCFC’s complaint devotes a good deal of attention to the fact that Fisher-Price has not shown any support for its contentions that the apps make babies smarter. But while this is all well and good for CCFC’s claim, CCFC’s weakest—and likely fatal—contention focuses on the second element of the claim: whether it is reasonable for parents to place a piece of technology in their baby’s hands and expect that baby to suddenly become smarter.

The strongest argument the consumer advocacy group can make concerns the first element. Fisher-Price has plainly made statements regarding its apparently deficient apps, and CCFC’s complaint devotes a good deal of attention to the fact that Fisher-Price has not shown any support for its contentions that the apps make babies smarter. But while this is all well and good for CCFC’s claim, CCFC’s weakest—and likely fatal—contention focuses on the second element of the claim: whether it is reasonable for parents to place a piece of technology in their baby’s hands and expect that baby to suddenly become smarter.

Much less ink is devoted by CCFC to this element of the unfair and deceptive trade practices claim, perhaps belying the weakness of its argument. CCFC, importantly, recognizes that a consumer’s interpretation of a marketing message “is reasonable if the consumer draws the conclusion that the advertiser intends to convey.” But what does “reasonable” mean? According to Black’s Law Dictionary, reasonable means “fair, proper, or moderate under the circumstances” or “according to reason.” Again, the circumstances matter when determining whether the parent has acted reasonably, and in this case, the second element of CCFC’s claim brings up two questions of what is reasonable: first, if the parents’ beliefs were reasonable; and second, if the parents’ actions were reasonable.

CCFC plainly does not want parents placing technology in a child’s hands as a learning tool replacement.

For CCFC to succeed, the group needs the first question to be the court’s focus of the analysis—whether the parents were reasonable in their reliance on Fisher-Price’s marketing message. But really, CCFC’s true focus is its underlying belief that parents need to be saved from themselves—that it is the parents who have not acted reasonably in the first place. The contradiction in CCFC’s position is exposed when CCFC discusses the third element of its claim—the materiality of the allegedly misleading representations. The discussion in the complaint turns from “making babies smarter” to “parents letting unsupervised children use technology.” One is a complaint about Fisher-Price; the other, a complaint about parenting techniques.

The real reason behind CCFC’s claim is not that parents have supposedly been duped into believing that their children would become smarter, but that those very same parents took the initial step themselves that makes CCFC’s claim possible. CCFC plainly does not want parents placing technology in a child’s hands as a learning tool replacement. This is the action that CCFC is really attacking—in a roundabout way—as being unreasonable.

The ease of access to the internet is no laughing matter when a small child is one touch away from opening up Safari and browsing the web.

CCFC has good reason to worry about babies and “screen time.” Within its complaint, CCFC references potential harm to brain development, learning development, and language acquisition as reasons for eliminating “screen time” for children under the age of two. The organization also references the potential for screen time to be addictive, as well as the negative “opportunity cost” of watching television without interacting with an actual person. An oft-cited American Academy of Pediatrics study from November of 2011 unquestionably provides support for CCFC’s concerns.

CCFC’s position, however, is not without dispute. Parents would undoubtedly be doing their children a disservice by taking the dramatic step of completely blocking use of new technologies, especially when those new technologies—like an iPad—are increasingly becoming the way people communicate. Likewise, screen time is not necessarily a completely bad thing for children, and there are certainly benefits to be had from embracing an entirely new way to play and interact with the world.

Yet, hindering a baby or small child’s ability to interact with others may be only one of many worries parents should have when handing their child an iPad. The ease of access to the internet is no laughing matter when a small child is one touch away from opening up Safari and browsing the web. And again, CCFC’s greatest worry is over the unsupervised use of technology.

Yet, hindering a baby or small child’s ability to interact with others may be only one of many worries parents should have when handing their child an iPad. The ease of access to the internet is no laughing matter when a small child is one touch away from opening up Safari and browsing the web. And again, CCFC’s greatest worry is over the unsupervised use of technology.

When it comes to accessing the internet in general—a natural next step from using iPad apps—few would argue that children should not be protected, and a vast array of government initiatives exist to accomplish this very goal. For example, the FTC recently announced that it is seeking public comment on ways companies can comply with the agency’s Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule, which requires parental permission before a child-friendly website can collect information from that child. Additionally, the Federal Communications Commission is focused on educating parents on the potential risks children face on the internet, and will be hosting a panel discussion to kick off its recognition of National Cybersecurity Awareness Month this October.

The U.S. Department of Justice has also recently raised awareness over the risks of children using the internet by participating in Child Cyber Safety Night at a Washington Nationals baseball game. Attorney General Eric Holder provided a statement for the evening, stating “As a parent, I understand the opportunities – and the challenges – that new technologies present for America’s young people. It’s up to each of us to start a dialogue with our kids about safe Internet and cell phone practices.”

CCFC’s intentions and its claim do not necessarily match.

In the end, the problem for CCFC’s complaint to the FTC regarding Fisher-Price is that its intentions and its claim do not necessarily match. Perhaps this fact is recognized by Fisher-Price and explains why the company has yet (as of the date of this publication) to change its marketing language for the respective offending apps. Fisher-Price should not take CCFC’s claims lightly, however, because the consumer advocacy group has had much success in the past with similar claims against the likes of Walt Disney Company and the marketers of Your Baby Can Read.

At the heart of this complaint about a toy company’s marketing practices, one must reflect on a question that would have been far from predictable in the world of children’s “learning” tools of the past: is handing your iPad to your months-old baby reasonable?