What to do with America’s spent nuclear fuel becomes a battle between the Branches of Government

A recent U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruling means the Nuclear Regulatory Commission will resume its review of whether Yucca Mountain is a suitable location for the storage of hundreds of thousands of metric tons of spent nuclear fuel.

In 2010, nuclear reactors supplied twenty percent (pdf) of America’s energy. Despite the continued and widespread use of nuclear energy, the disposal of the accompanying waste is among the more controversial topics in America, especially following the fairly recent leaks at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan. Nuclear energy provides consumers with a domestic energy source that produces few airborne omissions, but in the process, it creates nuclear waste that can be hazardous for one million years or more. Striking a balance between the continued use of nuclear energy and appropriate precautions for its storage has been a challenge since its inception. In an attempt to rectify this problem, Congress passed and President Reagan signed into law the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 (42 U.S.C § 10131 et seq.). Unfortunately, the law has never been properly effectuated.

In response to actions, or alleged inactions, by the Executive Branch, numerous parties sued the Department of Energy and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

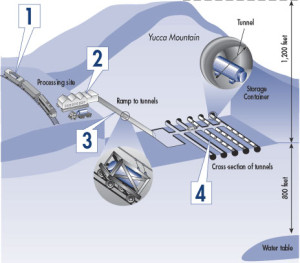

Following the enactment of the law, the Department of Energy began a search for suitable locations to house the country’s nuclear waste. It found nine potential sites, and further narrowed those to three by 1986. In 1987, Congress amended the statute to focus solely on the Yucca Mountain site in Nevada. At the time of the amendment, Congress envisioned the Yucca Mountain site receiving nuclear waste from reactors around the country by 1998. The Department of Energy, however, was unable to meet the 1998 date for the opening of the nuclear waste repository due to a number of factors, including state and local opposition. Nonetheless, the Department continued work on the Yucca Mountain site, and, in 2002, Congress chose the site as the location for the storage of the country’s nuclear waste. In 2008, the Department submitted a license application to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to construct the waste disposal repository at Yucca Mountain.

Beginning in 2009, different individuals and agencies within the Executive Branch began to call for the end of the project. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu wanted the Yucca Mountain project cancelled, and the Department of Energy followed, asking to withdraw the Yucca Mountain site’s application shortly thereafter. President Obama, in his budget requests for 2011, also asked that all funding for the Yucca Mountain project be withdrawn. In response to these actions, or alleged inactions, by the Executive Branch, numerous parties (including the states of South Carolina and Washington) sued the Department of Energy and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The plaintiffs have been seeking a writ of mandamus—an order from the court compelling an executive official to act—since 2010. The plaintiffs sought to have the court order the Department of Energy and Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to comply with federal law and continue the application process for the Yucca Mountain site. In July of 2011, a panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit held that the case was not ripe for adjudication (pdf). The plaintiffs brought another mandamus action in 2012, and the court suspended (pdf) the case in August of 2012 until Congress made its appropriations and showed its intent as to whether it wanted the application process to continue. The Department of Energy, the NRC, and Congress all failed to act on the issue, however, and the D.C. Circuit decided the case was ripe for adjudication.

The defendants offered several reasons for disregarding the statute. The Court found none persuasive.

The Appeals Court issued its opinion (pdf) on August 13, 2013, and granted the plaintiffs’ writ of mandamus, ordering the NRC to continue the application for the Yucca Mountain site. In doing so, the Court dealt with a number of constitutional issues involving the separation of powers between the three branches of the federal government. The Court began by defining the actions the President and the Executive Branch as a whole may take towards laws enacted by Congress. First, the President must follow Congressional mandates, as long as there are funds appropriated for the task and the President does not have a constitutional objection. The President and Executive Branch may not disregard a statute merely because of objections to the policy. These principles also apply to independent agencies like the NRC, and the plaintiffs argued that this was why the writ of mandamus should be granted.

The defendants offered several reasons for disregarding the statute. First, they argued, because Congress had not appropriated all of the money necessary to complete the project, they need not work on it further. Second, they assumed that because Congress had not yet fully funded the project or appropriated any money to the project in the last three years that the legislature would not appropriate any more money to the project in the future. Finally, the defendants argued that the low appropriations levels demonstrated a “congressional desire” for the NRC to shut down the process of licensing Yucca Mountain as the repository for the country’s nuclear waste. The Court found none of these arguments persuasive.

The majority determined that the NRC had approximately eleven million dollars to continue the project, but instead dismantled the project of its own volition. Chief Judge Merrick B. Garland dissented—taking a different view of the facts—believing that because the Commission had only eleven millions dollars to work with, a number insufficient to complete the task given it by Congress, the mandamus was not necessary. By issuing the mandamus to continue the process, the majority saw the issue as one of separation of powers; however, the dissent saw it more pragmatically. Chief Judge Garland believed that the Commission did not want to flout the law, just that the Commission could not make any significant progress with the amount of funds at its disposal.

Regardless of the political undertones, both the Executive and Legislative Branches must take action.

Despite the differing opinions between the majority and the dissent, the underlying, and still unresolved, issue is that of nuclear waste storage. The plaintiffs in the case were states, counties, affected individuals, and even nuclear power plants. The plants have been storing the waste at their own facilities, even though Congress, by enacting the Nuclear Waste Policy Act thirty years ago, believed it best if the federal government stored the waste created by nuclear power.

Some critics believe President Obama had made promises to Senate majority leader Harry Reid, who is both a Nevada native and a vigorous opponent to storage of the waste in Nevada, that he would stop the Yucca Mountain plan from coming to fruition. Regardless of the political undertones, both the Executive and Legislative Branches must take action. If, as the Nuclear Regulatory Commission believes, the money allocated it is not enough to seriously consider Yucca Mountain, Congress must allocate the necessary funds. If Yucca Mountain is not the answer Congress thought in amending the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to focus solely on that site in 1987, new sites need to be evaluated. The issue of what to do with America’s nuclear waste is not going away but only growing by the continued stalling in Washington.