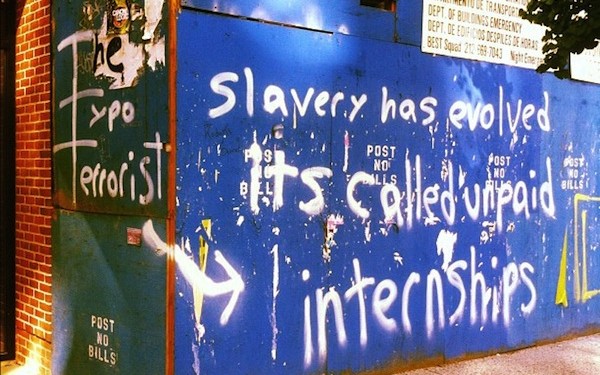

Second Circuit Rules Unpaid Interns Likely Not Employees Because of Educational Nature of Internship Programs

In an appeal to the Second Circuit, unpaid interns argue they are entitled to compensation, as they are employees – however, the Second Circuit rules that due to the educational nature of internships, in most cases, unpaid interns are not entitled to compensation based on a primary beneficiary test.

In 2013, interns of Fox Searchlight Pictures brought action against the company in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York alleging violations of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), New York Labor Law (NYLL), and the California Unfair Competition Law (CAUCL). These interns were classified as unpaid interns rather than as paid employees. Although the federal court held that the unpaid interns who worked for Fox Searchlight Pictures should have been classified as employees and even paid minimum wages, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit recently stated that the lower court’s decision was incorrect.

The general idea behind the lawsuit was that the unpaid interns believed they were part of a “centralized unpaid internship program,” where they were supervised and performed work that required them to be paid

Two of the plaintiffs to this action were unpaid interns working on the production of “Black Swan;” one of the two “Black Swan” interns took a second unpaid internship working on the film’s post-production, another unpaid intern worked on the production of “500 Days of Summer,” and another in Fox Searchlight Pictures’ corporate offices located in New York. The general idea behind the lawsuit was that the unpaid interns believed they were part of a “centralized unpaid internship program,” where they were supervised and performed work that required them to be paid. Fox Searchlight Pictures denied such a “centralized” internship program, and instead stated that the internships all varied and responsibilities and experiences were shaped by the particular interns’ supervisors.

In this case, the intern working for “500 Days of Summer” was barred from her claim because it was time-barred and she was aware of her claim much earlier than the other claimants. Specifically, this intern was aware that she was able to make minimum wage from her internship in 2008 and waited until 2013 to bring this suit, unlike the other unpaid interns who were unaware of their ability to make money from their internships until later.

The FLSA defines “employ” as “to suffer or to permit to work…”

The court looked to the FLSA and NYLL to define “employ” as its significance to Fox Searchlight Pictures in this case. The FLSA defines “employ” as “to suffer or permit to work,” and NYLL uses an almost identical definition. When determining whether one is employed, the court cites to the Second Circuit for guidance in a 1984 case, Carter v. Dutchess Community College, and a 2003 case, Ling Nan Zheng v. Liberty Apparel Company.

The Carter case outlines a test to aid in determining whether there is an employment relationship under the FLSA by considering four factors. The four factors are utilized to see whether “formal control” over an employee is present: 1) whether the employer had power to hire and fire the workers, 2) whether the employer supervised and controlled the work schedules or conditions of the workers’ employment, 3) whether the employer determined the workers’ payment rate and method, and 4) whether the employer maintained employment records for that worker.

The Zheng case outlines a test in which six factors are articulated to determine whether an employer exercises “functional control” over an employee. This case determines “functional control” even if the employee lacked formal control, as articulated in Carter. The six-factors include: 1) whether the employer’s premises and equipment were used for the performance of the worker’s work, 2) whether the workers “had a business that could or did shift as a unit from one putative joint employer to another” employer, 3) the extent to which the workers performed a specific job integral to the employer’s production, 4) whether responsibilities under the employment contracts could pass from one worker to another worker without any material changes, the degree to which the employer or the employer’s agents supervised the work of the worker, and 6) whether the workers “worked exclusively or predominantly” for the employer.

The District Court for the Southern District of New York found that the plaintiffs were victim to the common practice of employers attempting to replace paid employees with unpaid interns

The District Court for the Southern District of New York found that the plaintiffs were victim to a common practice of employers attempting to replace paid employees with unpaid interns. The case was widely-watched. Depending on the ruling, large corporations and Hollywood would be affected and forced to pay their unpaid interns based on their work.

The importance of this case was whether employers would be required to pay their unpaid interns under certain circumstances. When a worker is classified as an employee, the Fair Labor Standards Act is activated requiring the employer to compensate the workers for the work performed. The FLSA requires a certain minimum wage, over time, and other benefits.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reviewed this case and found that the district court got it wrong. The Court states that the issue to be decided is when is it required for an unpaid intern to be considered and classified as an “employee” under the Fair Labor Standards Act, therefore requiring compensation for the unpaid intern’s work. The Court establishes the Primary Beneficiary Test, holding that the proper inquiry in dealing with unpaid intern employee classification is to determine whether the intern or the employer is the primary beneficiary of the relationship.

The Court notes that the purpose of unpaid internships is to provide educational training to interns and provide benefits to the interns

In its opinion, the Court highlights the Department of Labor’s Intern Fact Sheet providing for what must be present for an employment relationship to not exist. The fact sheet includes: 1) the internship is similar to training, which would be given in an educational environment, even though it includes the actual operation of the facilities of the employer; 2) the internship experience is for the benefit of the intern; 3) the intern does not take the place of regular employees, but instead works closely with supervisors; 4) the employer providing the training does not receive immediate advantage from the intern’s training; 5) the intern does not necessarily receive a job at the conclusion of the internship; and 6) the employer and intern understand that the intern is not entitled to compensation for the time spent or work performed in the internship. The Court of Appeals noted that while the district court did use these factors in evaluating the case, it did not require that all six factors be met, unlike the Department of Labor.

Further, the Court of Appeals states that whether an unpaid intern is entitled to compensation for the work performed during the course of their internship is a matter of first impression in the Second Circuit. The Court notes that the purpose of unpaid internships is to provide educational training to interns and provide benefits to the interns.

However, the Court does recognize the potential for an employer to exploit the unpaid internship programs for free labor. As a result, both parties agree that there are instances where an unpaid intern is actually an employee and entitled to compensation, and there are instances where an unpaid intern is not an employee and is actually not entitled to compensation.

The Court favors the primary beneficiary test in that it focuses on what the intern receives in exchange for his or her work, and permits courts the flexibility to consider the economic reality between the intern and employer on a case-by-case basis

In this case, the Fox Searchlight Pictures defendants want a primary beneficiary test, which would be a standard where an employment relationship is created when there are tangible and intangible benefits provided to the intern are greater than the intern’s contribution to the employer. This approach would provide for a totality of the circumstances consideration. While the Department of Labor writes separately in support of the unpaid intern plaintiffs to the Second Circuit urging for the court to follow the six-factors laid out in the Intern Fact Sheet, the Court finds this approach too rigid and goes for the primary beneficiary test.

The Court favors the primary beneficiary test in that it focuses on what the intern receives in exchange for his or her work, and permits courts the flexibility to consider the economic reality between the intern and employer on a case-by-case basis. When considering what may be used in applying the Primary Beneficiary Test, the Court cites to seven factors that have been laid out in past cases that employers may utilize, among other facts, in applying the Primary Beneficiary Test to their individual circumstances.

Those seven factors include: 1) the extent to which the intern and employer understand there is no expectation of compensation, 2) the extent to which the internship provides training similar to that which would be given in an educational environment, 3) the extent to which the internship is tied to the intern’s formal education program through integration into coursework or where the intern receives academic credit for the internship, 4) the extent to which the internship aligns with the intern’s academic commitments during the academic year, 5) the extent to which the internship’s duration is limited to a period where the intern receives beneficial learning, 6) the extent to which the intern’s work complements paid employees instead of replacing them, and 7) the extent to which the intern and employer understand the internship is conducted without being entitled to a job after the internship has concluded. While no one factor is dispositive, each of these factors has been previously utilized in other cases to determine whether a worker is an employee. As such, employers are able to utilize these factors in applying the Primary Beneficiary Test to their individual cases.

The nature of internships provides interns with educational value, and often interns receive educational credit for their work during the course of the internship

The court focuses its attention on the unique nature of an internship. The nature of internships provides interns with educational value, and often interns receive educational credit for their work during the course of the internship. It is because of this potential for educational value and education credit that the court finds that in this situation, the unpaid interns were not employees for the purposes of the FLSA, and instead were not required to be compensated.

This decision leaves non-employees, such as independent contractors, interns, unpaid interns, etc., wondering what is next. Will there be challenges to current pay structures or employment classifications? Will employers take notice of this decision and shift their ways?

What would be ideal for employers to do is to look at their current employment structures and ensure they align with the factors outlined in this decision, and others similar. Since the focus of the court in this case was the educational value and the benefit given mostly to the intern as opposed to the employer, it would be beneficial for employers to implement strategies within their internship programs where it takes the form of more of a learning period, where there are maybe daily logs, and even periodic conferences to discuss what the intern is learning and what else they would like to learn to enhance their experience. As educational as the employer can make the experience, it seems, the more likely they can justify not paying an intern.

If the Second Circuit found that there may be instances where unpaid interns could be considered employees, does this open the door to many other claims regarding lack of compensation or employment status?

While the Second Circuit focuses on the educational value, interns may be able to poke holes in this argument if given certain tasks by their employers. Certainly the purpose of internships is to mostly give experience and educational value or academic credit. However, so often the internship program seems more like a temporary job assignment than it does a learning experience.

The Second Circuit found here that the unpaid interns were not employees. However, it did recognize the potential for unpaid interns to be taken advantage of and used as free labor to cause the employer to not have to hire a paid employee. If the Second Circuit found that there may be instances where unpaid interns could be considered employees, does this open the door to many other claims regarding lack of compensation or employment status? Will there be a rise in lawsuits over this issue?

Will interns even find it valuable or beneficial to bring action against employers they may feel are violating the FLSA? In our economy, so often students are simply looking for jobs after they graduate from school. Internship programs put you in contact with potential future employers. While everyone is entitled to fair treatment in the workforce, the question is whether interns even feel it is possible for them to challenge how they are treated out of fear for repercussions.

Issues with employee misclassification have caused the North Carolina General Assembly to take notice

Employee misclassification has become such a large issue across the nation – but why? Having employees as opposed to independent contractors, or in this case unpaid interns, requires employers to abide by certain labor laws with regard to benefits, pay regulations, and even accommodations. Issues with employee misclassification have caused the North Carolina General Assembly to take notice.

The North Carolina House of Representatives is currently hearing a bill that will establish an Employee Classification Division—the Employee Misclassification Reform Bill. The Division will be located within the Department of Revenue and will focus its attention on identifying and investigating alleged instances of employee misclassification.

The North Carolina House Bill also attempts to define an independent contractor and employee. The bill identifies factors to consider when determining whether a workers is an employee or an independent contractor as derived from Hayes v. Board of Trustees of Elon College: (1) whether the worker is engaged in their own independent business; (2) whether the worker has independent use of his or her own skill, knowledge, or training; (3) whether the worker is doing specified pieces of work at fixed prices or is doing work for a lump sum or on a quantitative basis; (4) whether the worker is subject to discharge by adopting their own style of doing work; (5) whether the worker is in the regular employ of the employer/contracting party; (6) whether the worker is free to use assistants as they see fit; (7) whether the worker has full control over those assistants; and (8) whether he selects his or her own time or has a set schedule by the employer/contracting party.

Cases have tried multiple times to identify an employee as opposed to an independent contractor. Regardless of the attempts at identification, confusion continues to arise with various employee classification issues. Whether the Employee Classification Division will assist with instances of employee misclassification in North Carolina is dependent on the success of the legislation and its implementation.