Supreme Court Agrees to Review the Employer Contraception Opt-Out Option

After the Eighth Circuit refused to deny the argument that the opt-out option to the contraception mandate of the Affordable Care Act violated employers’ religious freedoms, the Supreme Court agreed to take on and consolidate seven cases regarding this issue to hopefully give proper guidance on whether the opt-out accommodation violates the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

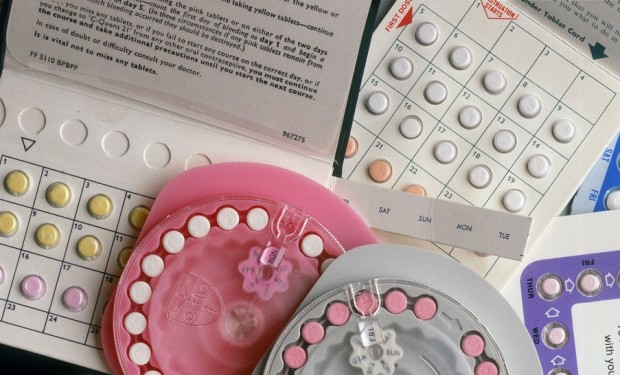

After Burwell v. Hobby Lobby was decided in June of 2014, questions remained as to whether the contraception mandate of the Affordable Care Act finds a way to continue to violate employers’ religious freedoms. The Affordable Care Act (“the Act”) has a contraception mandate, which requires employers to provide contraception coverage in their health coverage plans. Hobby Lobby contested this provision of the Act by stating that the contraception mandate violated their religious freedoms under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). The Hobby Lobby decision made it so that for-profit companies could deny their employees health coverage for birth control and other contraception that their religion viewed as “funding abortion.”

The Eighth Circuit … held for the opposing religious nonprofit organization that claimed that by playing a role in allowing contraceptive coverage at all would be a violation of their religious beliefs.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit stood out from other circuit courts that have rejected the argument that the opt-out option substantially burdens religious freedom and instead approved the argument at the opt-out makes objecting parties morally complicit in providing access to birth control. The Eighth Circuit, in Dordt College v. Burwell, held for the opposing religious nonprofit organization that claimed that by playing a role in allowing contraceptive coverage at all would be a violation of their religious beliefs.

While the opt-out accommodation allows religious nonprofit organizations opposed to providing mandatory contraception coverage an option to not provide the coverage, many still object. The plaintiffs in Dordt College claimed that even if it meant making birth control pills and contraceptive devices available just to opt-out of that specific portion of coverage, this would still be a violation of their religious beliefs. This decision caused a circuit split on whether the opt-out accommodation was a violation of RFRA.

The Supreme Court decided to take on and consolidate seven cases all dealing with the issue of whether the opt-out option to the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate violated religious freedoms of religious nonprofit organizations under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The cases all involve different situations, scenarios, and employers with different insurance plans, but all with a common objection—the opt-out option morally compels them to arrange access to birth control, in violation of their religious freedoms.

[T]he Third Circuit stated that the self-certification procedure where you fill out a form so you are exempt from providing contraception services in your healthcare policy is not overly burdensome and does not facilitate the provision of contraceptive coverage.

In Zubik et al. v. Burwell et al., the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit was called to determine whether the “opt-out” accommodation and the contraception mandate violated RFRA in forcing religious nonprofits to act in violation of their sincerely held religious beliefs. The plaintiffs argued that the government had not proven that this contraception mandate is the least restrictive means of advancing any compelling interest, and therefore violates their religious freedom. Specifically, they allege that the say the accommodation forces them to facilitate the contraceptive services provision of their insurance coverage, and that violates their religious freedoms, as they oppose the idea of contraception.

The plaintiffs in Geneva College v. Burwell et al. called for the Third Circuit to determine whether the Act’s contraception mandate imposes on religious nonprofit organizations a substantial burden in their religious exercise, and therefore violates RFRA. Further they allege that their requirement to opt-in to the coverage of the contraceptive services violates their rights.

The plaintiff-appellees argue that in self-certifying and filling out the form to become exempt from providing the mandated contraception coverage, they are in turn being “complicit in sin,” and as such, this causes them to go against their religious beliefs and violates their religious freedoms. They argue that when they self-certify, it forces them to trigger the contraception coverage that they ordinarily would not have triggered or provided. In essence, they argue that in order to opt-out they must first opt-in to providing contraception coverage in their health coverage.

The Third Circuit consolidated these cases and held that the plaintiffs have failed to show that the opt-out accommodation imposes a substantial burden on their religious exercise. As such, their appeal failed, and the Third Circuit did not rule on whether the opt-out accommodation was the least restrictive means of furthering a compelling governmental interest. In its opinion, the Third Circuit stated that the self-certification procedure where you fill out a form so you are exempt from providing contraception services in your healthcare policy is not overly burdensome and does not facilitate the provision of contraceptive coverage.

[The D.C. Circuit] held that RFRA gives the plaintiffs a right to be free from any unjustified substantial governmental burden on the plaintiffs’ religious exercise, and the opt-out accommodation does just that.

The United States Court of Appeals for District of Columbia Circuit, in Priests for Life et al. v. HHS et al., was asked to determine whether the contraception mandate in the Affordable Care Act as applied to non-exempt, nonprofit religious organizations violates RFRA. Here, the plaintiffs argue that the accommodation does not do enough to prevent their religious freedoms from being violated. They allege that the accommodation allows them to opt-out of coverage, but that it still requires them to “play a role in facilitating contraceptive coverage.” They further allege that the government lacks a compelling interest that would require them to comply with the opt-out accommodation, and that in doing so, they are substantially burdened I their religious exercise.

The Court in Roman Catholic Archbishop v. HHS et al. was to decide the issue of whether RFRA allows the government to force objecting religious nonprofit organizations to violate their beliefs by offering plans that contain contraceptive coverage. The plaintiffs here argue that being required to offer health coverage plans that include contraceptive coverage in order for them to take advantage of the opt-out requires them to violate their religious beliefs, and therefore is a violation of RFRA.

The D.C. Circuit consolidated these two cases and held that the government has substantiated its compelling interests in the accommodation by promoting public health and gender equality. Further, they held that RFRA gives the plaintiffs a right to be free from any unjustified substantial governmental burden on the plaintiffs’ religious exercise, and the opt-out accommodation does just that. It simply requires that the plaintiffs fill out a piece of paper to signal their desire to not provide contraception coverage to their employees as per their sincerely held religious beliefs. The D.C. Circuit even throws in a statement that RFRA provides them freedom from unjustified substantial governmental burden on their exercise of their religion, but it does not entitled the plaintiffs to “control their employees’ relationships with other entities willing to provide health insurance coverage to which the employees are legally entitled.”

The Tenth Circuit … held that the opt-out accommodation relieves the plaintiffs of their obligations to comply with the contraception mandate, not the other way around.

In Southern Nazarene University et al. v. Burwell et al., the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit was asked to determine whether the alternative means for religious nonprofit employers to comply with the Act, through the opt-out alternative, changes the substantial-burden analysis or identification of a free exercise violation from Hobby Lobby. The plaintiffs allege that the opt-out alternative poses a substantial burden on their exercise of religion, and that it The plaintiffs argue, among multiple other Constitutional issues regarding free speech and the validity of the mandate as a whole, that their compliance with the mandate or the accommodation impose a substantial burden on their religious exercise because it forces them to trigger the contraception coverage when they opt-out.

The Court in Little Sister of the Poor et al. v. Burwell et al. was asked to determine whether the opt-out accommodation for nonprofit religious employers to comply with the Act eliminates the substantial burden on religious exercise or eliminates the violation of RFRA recognized in Hobby Lobby. It also asks the Court to determine whether The Department of Health and Human Services satisfies RFRA’s test for overriding sincerely held religious beliefs where the Department itself insists that overriding the religious objection will not fulfill the Departments objective of providing contraceptive coverage to Americans.

The Tenth Circuit consolidated these two cases and held that the opt-out accommodation relieves the plaintiffs of their obligations to comply with the contraception mandate, not the other way around. The Tenth Circuit further states that it does not substantially burden their religious exercise because the accommodation exempts them from having to participate in the contraception mandate altogether. Further, the Court here states that opting out of coverage does not cause contraception coverage. It also states that the opt-out provision does not eliminate the requirements of Hobby Lobby, but provides an opportunity for these religious nonprofit organizations to be excluded from complying with the contraception mandate of the Act.

The Fifth Circuit does not buy the plaintiffs’ arguments and instead states that the providing of names and contact information only facilitates their exemption [from providing contraception coverage], not contraception coverage itself.

In Texas Baptist University et al. v. Burwell et al., the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit was asked to determine whether the opt-out eliminates the substantial burden on religious exercise or the violation of RFRA as recognized in Hobby Lobby. The plaintiffs in this case believe contraception to be a form of abortion, and the plaintiffs oppose being required to provide contraception. They also oppose the accommodation because it forces them to provide their names and contact information and therefore facilitates their providing contraception. They also argue that by filling out the form to opt-out, in essence makes them eligible for the government’s reimbursement of contraceptives.

The Fifth Circuit does not buy the plaintiffs’ arguments and instead states that the providing of names and contact information only facilitates their exemption, not contraception coverage itself. The Court further clarified that while it may make them eligible for reimbursement, it also is the means by which they are to opt-out of the coverage, thereby taking away that eligibility. The Fifth Circuit does not find that the plaintiffs have been substantially burdened, and therefore uphold the opt-out provisions for these plaintiffs.

… [I]t appears the challenge in this consolidated case does even more [than Hobby Lobby], and goes to the heart of the religious debate – contraception, and whether contraception coverage should be required.

The fact that the Supreme Court decided to take on all seven of these cases, and consolidate them into one case shows that the Court is serious about making a decision that will be wide-reaching, and hopefully settle the issue (for now). But, what will the Court likely to do? Will it side with the employers who wish to not provide contraception under their religious freedoms, but feel that the opt-out still morally compels them to provide contraception? Or will it side with employees, who wish to have contraception covered under their employer’s health insurance plans, as is required under the Act?

This decision will be a landmark decision in that it will provide much guidance as to whether the opt-out option is permissible or whether it violates employers’ religious freedoms. In the Hobby Lobby case, the Supreme Court was able to still rule that the contraception mandate of the Act was legal and permissible, while finding a compromise for employers who have stern religious beliefs that prevent them from complying. However, it appears the challenge in this consolidated case does even more, and goes to the heart of the religious debate – contraception, and whether contraception coverage should be required.

Certainly, the issue here is whether the opt-out to the contraception mandate of the Act still violates employers’ religious freedoms in that it morally compels employers to still provide the contraception in their health care plans. However, this issue is broader than just that. These cases challenge the idea that the contraception mandate should even be required under the Act at all.

The opt-out accommodation was a compromise/accommodation the Supreme Court implemented in the Hobby Lobby decision to keep intact the contraception mandate, but also prevent the violation of the for-profit company’s exercise of religion.

If these cases are successful, and the Supreme Court sides with the Eighth Circuit and the objecting employers, where will this leave the contraception mandate? The opt-out accommodation was a compromise/accommodation the Supreme Court implemented in the Hobby Lobby decision to keep intact the contraception mandate, but also prevent the violation of the for-profit company’s exercise of religion. If the opt-out is deemed to not be permissible because it still violates employers’ religious freedoms, the Supreme Court will have to go back to their accommodation from Hobby Lobby, and find a new means of accommodating religious beliefs under the Act.

Will this in essence be seen as the Supreme Court stating that because the contraception mandate violates religious freedoms, there isn’t much of a compromise, and therefore employers don’t have to comply with the mandate? Will this open the door for further litigation and challenges to other aspects of the Affordable Care Act?

The Supreme Court is going to have to really consider the law in this case and the repercussions of their decision. When the Supreme Court set the compromise opt-out option for employers who felt their religious freedoms were being violated by being forced to cover contraception in their health coverage for employees, it somewhat acknowledged that the contraception mandate could be seen as a violation of the employers’ religious freedoms. The decision, though, did not entirely deem the contraception mandate unconstitutional, but rather provided an exception to the contraception mandate requirement.

As such, it is not likely that the same court that decided the Hobby Lobby case and determined that the opt-out option was a constitutional compromise is going to partially overrule that decision and determine that their accommodation was in fact not constitutional. With seven circuit courts acknowledging that the opt-out accommodation does not violate RFRA, but instead provides an opportunity for objecting religious nonprofit organizations to not provide contraceptive coverage, and one circuit court recognizing the argument that the opt-out accommodation imposes a substantial burden, the Supreme Court’s potential ruling is not obvious. However, the fact that the Supreme Court took the case out of the small amount of cases it takes every year, even in the consolidated form, should say a lot.

Regardless of the decision, it will be a crucial outcome for the ACA and RFRA arguments in the future.