Will gerrymandering in North Carolina ever come to an end?

Given North Carolina’s history with redistricting and its continuous struggle with gerrymandering district lines, a recent lawsuit regarding the 2011 redistricting forced North Carolina legislators to take another look at the district lines.

Congressional districts of North Carolina have long been an issue for the State. In 2014, the Washington Post came out with a list of the most gerrymandered congressional districts in the nation. Three of the top ten districts were in North Carolina. Two of those districts were the twelfth and the first most gerrymandered. The United States Circuit Judge Roger L. Gregory, along with two district judges, found two of these districts, the twelfth and the first, unconstitutional on February 5, 2016, forcing the North Carolina General Assembly to take a second look at the lines it drew.

Challengers to the [NC] map say that the districts were drawn strictly based on race lines, violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Congressional districts are drawn based on decennial census data, taken every ten years. All congressional districts must also comply with the Voting Rights Act. The current challenge to the North Carolina districts comes from the version drawn in 2011. Challengers to the map say that the districts were drawn strictly based on race lines, violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In formulating its opinion, the court looked at the history surrounding the two districts at issue in the case. Although district one did not previously have a black majority, its black voting population still hovered around 46 percent. In 2001, it was redrawn to increase that number, and again in 2011 to the challenged version now existing. Even without the majority of voters, African-American preferred candidates won consistently with at least 59 percent of the votes in the first district. There were no previous challenges to former versions of district one, but the federal court found significant issue with the way it was drawn.

[The twelfth district] was a thin, narrow line that ran from a carved out portion of Charlotte through north of Greensboro.

The twelfth district is perhaps the worst of the gerrymandered districts. The district was a thin, narrow line that ran from a carved out portion of Charlotte through north of Greensboro. This district was put together to group minority, mostly democratic voters. Even before it was drawn as a minority-majority, the district had 46 percent black voters.

From 1993-2014, district twelve had the same Congressman, Melvin Watt. Watt, a democrat, was an attorney in Charlotte and a one-term congressman when the district took shape. Watt rarely had opposition, and when he did that opposition received little votes, often less than 30 percent. When the district was redrawn in 2011, the black voting population increased to over 50 percent. As someone who grew up in this district, and as a voter, it is frustrating to feel as if your vote doesn’t count, and it feels fundamentally unfair to condense black voters to specific districts.

Prior to the case at issue, there was an unsuccessful state court challenge by the NAACP to the congressional districts of 2011.

This was not the first lawsuit that the twelfth district was involved in, however. In 1993, Shaw v. Reno, was brought as a racial challenge to the district lines, claiming that the district was intentionally drawn to create a minority-majority district. The case made it all the way to the Supreme Court and ended in a 5-4 decision. The Court said that the case had to be decided under strict scrutiny, under the Equal Protection Clause. Actions subject to strict scrutiny must have a compelling interest, narrowly tailored efforts, and the least restrictive means. Shaw was to be applied to future redistricting efforts and the cases arising out of those efforts.

Prior to the case at issue, there was an unsuccessful state court challenge by the NAACP to the congressional districts of 2011.

The current challenge to the first and twelfth districts arise from David Harris from district one, and Christine Bowser from district twelve. They sought a declaratory judgment that the districts were unconstitutional as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. They also sought an injunction to bar North Carolina from having the congressional elections under the 2011 maps.

North Carolina legislators argued that they drew the districts this way in order to comply with section two of the Voting Rights Act. This section prohibits discrimination on the basis of race. This prohibition against discrimination in voting applies nationwide to any voting standard, practice, or procedure that results in the denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group.

On February 5, 2016, a three judge panel of the Fourth Circuit ruled that the first and twelfth districts were unconstitutional and must be withdrawn.

Due to the case’s allegations of unconstitutionality of the congressional districts, the chief judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit granted the plaintiffs’ request for a three-judge panel hearing. To be successful, the plaintiffs had to show that race was the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision to place a significant number of voters within or without a certain district. According to the court, the plaintiffs met this burden with unspecified evidence showing that the legislatures had racial quotas for the two districts.

The State of North Carolina had the chance to rebut the plaintiff’s case, if they could prove a compelling interest and that the means were narrowly tailored. Narrow tailoring requires that the legislature have a “strong basis in evidence” for its race-based decision, or good reasons to believe the classification was required in order to comply with the Voting Rights Act. Here, the court found that evidence of a narrowly tailored interest was “practically non-existent.” North Carolina only offered evidence as to district one, and no evidence for district twelve.

On February 5, 2016, a three judge panel of the Fourth Circuit ruled that the first and twelfth districts were unconstitutional and must be withdrawn. The court ruled that these districts were drawn so that the majority of voters in the districts were black. Judge Gregory wrote for the court that partisan claims were an afterthought rather than a clear objective. State lawmakers were upset by this decision with the March 14 primary being moved and many absentee ballots having already been cast.

[The court] gave North Carolina legislators two weeks from the date of decision to redraw the unconstitutional districts.

The United States District court, finding that defendants failed to satisfy strict scrutiny, gave North Carolina legislators two weeks from the date of decision to redraw the unconstitutional districts. The plaintiffs requested that the Court have a say in the redistricting, but they declined, noting both Supreme Court language and North Carolina law.

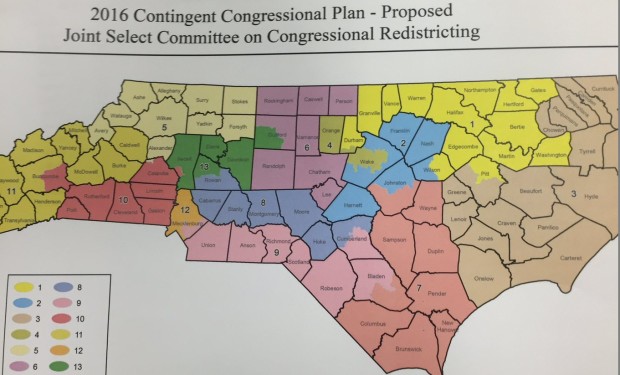

Redrawing the districts proved difficult. Also, the gerrymandered, mostly democratic districts were originally drawn by a legislature composed of a majority of Republican legislators, making some wary again as to whether they would redraw them in a way state democrats would approve. After a week of discussion, the North Carolina General Assembly revealed its new congressional district map, with obvious changes from the 2011 version. Now, the elections can continue free from lawsuits. State legislators attempted to get a stay from the Supreme Court, but they declined this request. Many lawmakers feel this was affected by the death of Antonin Scalia, who was rumored to be voting in favor of the stay.

The new congressional districts have changed the voting of thousands of North Carolina Citizens. WRAL has provided a map, in which you can insert your address to see if your district has been changed. The new congressional primary election is set for June 7, 2016, and the thousands who have already cast absentee ballots will have the opportunity to revote. The state chapter of the NAACP is still against the new district map, and it is unknown if any further legal action will be taken.