Do national letters of intent perform a service or disservice?

With binding terms and little room for negotiation, national letters of intent may do more harm than good for college athletes.

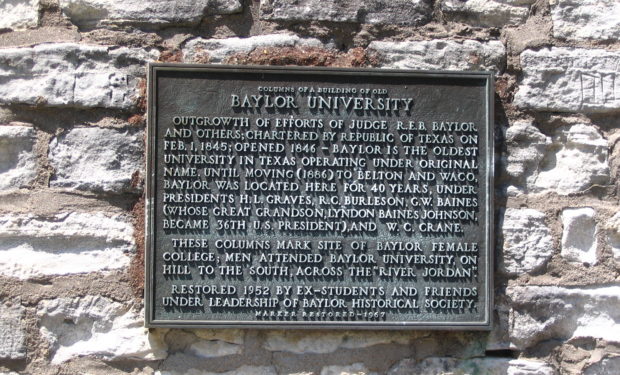

In the wake of the recent Baylor athletic scandal, seven top football recruits who had previously signed National Letters of Intent (NLI) committing themselves to Baylor University, requested that they be released by the university from their commitments. The recruits’ concerns are well founded, as head football coach Art Briles was recently fired, Baylor Athletic Director Ian McCaw resigned, and the possibility of NCAA sanctions looms. Clearly these recruits feel it is in their best interests to display their talents at another university, where they feel they can trust the coach, the school, the system, and most importantly their own opportunity for success. Unfortunately for these NLI signees, the decision about where they will play can only be made by Baylor University. That begs the question, do student-athletes really understand what they are doing when they sign the NLI and, if so, is there any way out of that commitment?

The NLI binds the recruit and the university, explicitly excluding any coach from a role in that agreement. Only the university may release a recruit from their NLI, and even then, only after a lengthy appeals process.

Every year, thousands of athletic program recruits choose their home for the next four years at any number of universities. A variety of factors go into these decisions, ranging from academic prowess, to the types of training facilities made available by university athletics. Many recruits choose to attend universities because of particularly good relationships with coaches, or because they value the university’s athletic “brand.” Commitment ceremonies from the classic hat selection to more adventurous selection reveals have become wildly popular in recent years, particularly among top athletic prospects. These, however, are generally non-binding verbal commitments. For many recruits, the real commitment is their signing of the National Letter of Intent.

The NLI is founded in contract law, as the NLI is simply a contract binding recruits to universities. Recruits commit to only play for one university, and in exchange that university guarantees at least one year of financial aid. However, it is quite important to read the fine print when considering the NLI. Fittingly, the NLI only goes into effect if the recruit can gain acceptance to the university. The NLI binds the recruit and the university, explicitly excluding any coach from a role in that agreement. Only the university may release a recruit from their NLI, and even then only after a lengthy appeals process. If a recruit breaks their agreement with the university, the NCAA requires that player to be ineligible for one season. Overall though, the NLI seems to serve a valuable purpose for both universities and recruits.

The NLI program was started in 1964 by the (at that time) seven major athletic conferences. The intent of the NLI was to control the growth of national recruitment over purely local recruitment. At the time there were major problems with universities luring top recruits away from the programs the recruits had originally committed to join, compounded by the rise of television media and popularization of college sports in the decades preceding. Creating an avenue for recruits to secure financial aid while athletic programs received peace of mind about their recruiting class was and remains a common sense solution. However, said solution may need to be revised to reflect the realities of twenty-first century collegiate athletics.

Over the years, the legal requirements of the NLI have been updated several times. One example is the requirement that the parents or legal guardians of recruits under 21 years of age must sign alongside their recruit. Many question the need for the NLI’s parental consent requirement to be extended all the way to 21 year olds, but most agree that the parental consent requirement is a necessary provision to secure NLI’s against the “infancy doctrine.” The infancy doctrine operates under the legal fiction that minors lack the capacity to enter into contracts, and therefore may generally void any contracts they have entered into. The entire purpose of the NLI would be ruined if 16 or 17 year old recruits could secure a promise of financial aid from a university, only to later recant and take a better offer.

However, in this case, a parent could not suit up and play for their child. And the fact is, an alternate punishment system is in place for non-performance, which tends to suggest that the parent’s signature is no form of surety.

Football recruits from Baylor University likely would not be able to use the infancy doctrine as a loophole to get out of their contracts because of the NLI’s parental consent requirement. Parents cosigning NLI’s with their children likely adds the capacity element to a minor’s decision. Still, some question whether the parental consent requirement actually has any legal effect. Parents generally cosign with their children as a surety. In the case that the child reneges on the contract, the parent can perform in their child’s place. However, in this case, a parent could not suit up and play for their child. In fact, an alternate punishment system is in place for non-performance, which tends to suggest that the parent’s signature is no form of surety. Whatever the case, this is not a likely avenue that the Baylor football recruits will take to remove themselves from the constraints of the NLI.

As parental consent was a question in the past, the current question is whether recruits are getting the benefit of their bargain when they sign the NLI. In O’Bannon v. NCAA, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held that college athletes have a right to compensation for the commercial use of their likeness. A debate continues to rage among athletes, university officials, and media over whether college athletes should be compensated for their participation in collegiate athletic programs. College athletes are even seeking to form a union to protect their interests, though a recent decision by the National Labor Relations Board declined to extend employee status to Northwestern University athletes, placing unionization on hold for now. Many believe it is only a matter of time before college athletes are paid for their services. In the midst of this debate, the NLI stands as a major legal roadblock to college athletes ever being paid.

The reality of the contract that recruits typically must sign to play college sports is that it allows no room for compensation. The NCAA does not allow negotiation of the terms of the NLI, including negotiation regarding the stability of the athletic program and coaching staff. The NCAA does not even allow negotiation of the length of time recruits will receive financial aid. All the power five conferences recently took a step in the right direction by mandating that all scholarship offers be four years in length, but plenty of other universities still practice a system where after one year, nothing is guaranteed to recruits who have signed the NLI.

The strict requirements of the NLI may ultimately raise the question of unconscionability in future dealings where recruits wish to negotiate contracts that reflect their value both as players and as commercial assets to their university’s athletic program. Under section 2-302 of the Uniform Commercial Code, a court may determine “whether, in light of the general commercial background and the commercial needs of the particular trade or case, the clauses involved are so one sided as to be unconscionable” at the time of the making of contract. Several cases, including Campbell Soup Co. v. Wentz out of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, comment that the principle of unconscionability is used to prevent “oppression and unfair surprise” rather than controlling where risks are placed.

While Article 2 of the UCC only applies to contracts for the sale of goods, the language concerning unconscionability in Article 2 reflects a widely accepted legal theory. As Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote in United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., “[d]oes any principle in our law have more universal application than the doctrine that courts will not enforce transactions in which the relative positions of the parties are such that one has unconscionably taken advantage of the necessities of the other?” Essentially, a contract is unconscionable at common law when one party to a contract has unreasonably taken advantage of the other party’s necessity.

The recruits would argue that their contract with Baylor through NLI areunconscionable because of the sudden departure of head coach Art Briles, immeasurable damage done to Baylor’s football brand, and the possibility of NCAA sanctions, which all act as an unfair surprise.

Herein lays the heart of the argument between Baylor University and their football recruits. Though disputes over pay and commercial use of likeness may soon be a reality universities face when recruiting, the recruits in this case are worried about being put at a disadvantage by Baylor’s failures as a university. The recruits would argue that their NLI’s are procedurally unconscionable because the necessity of signing a boilerplate contract to receive financial aid essentially leaves recruits without the ability to negotiate, and substantially removes any choice from their decision to sign contracts. The sudden departure of head coach Art Briles, the immeasurable damage done to Baylor’s football brand, and the possibility of NCAA sanctions all act as the substantively unconscionable result of these contracts. As a result, Baylor’s football recruits must now remain in a toxic program without ever having had an opportunity to negotiate for an exit from these kinds of situations. Baylor would likely rebut that the recruits’ agreement was not contingent on a good brand or a head coach, but on Baylor University providing them with the means to attend the university. Furthermore, Baylor could point out that signing the NLI is voluntary, although receiving any kind of financial aid is generally contingent on signing the NLI.

That is where things might get interesting. The cause of Art Briles’ firing and the crushing blow to Baylor University’s football program is an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice. Essentially, Baylor is being investigated for disregarding Title IX requirements dealing with sexual assault allegations and support systems for victims of sexual assault. Title IX clearly provides that part of providing education is investigating allegations of sexual assault and providing support services for those who have been sexually assaulted. The Baylor football recruits’ NLIs were arguably contracts for Baylor University to provide the recruits with an education since Baylor, a member of the Big 12 conference, is subject to the mandate on offering four year scholarships. Baylor would clearly argue that their obligations under the NLI are limited to providing the funding for recruits to receive education and not providing the education itself. However, as previously mentioned, one of the prerequisites for signing an NLI is being accepted to the university making the offer (i.e. – being offered an education). If Baylor is contractually obligated by the NLI to provide their recruits with an education, the football recruits may be able to challenge that failure to provide educational facilities compliant with Title IX as a breach of contract. Such a breach might not ultimately result in a discharge of the recruits’ NLI’s, but it might be worth a challenge.

The bigger point is that NCAA must consider changing the NLI. Doing away with the NLI entirely is not a desirable solution to these issues, as it does serve an important interest in binding universities to recruits and removing some of the chaos and disorder from the recruitment process. However, to cope with a likely future trend toward payment of student-athletes, the NCAA must broaden the language of the NLI to give recruits some negotiation power regarding program stability and even commercial use of their individual brand as players. Anything less would do a disservice to college athletes, a disservice clearly on display as several Baylor football recruits fight to be released from their National Letters of Intent.