Congress ignores President Obama’s warnings.

By overriding President Obama’s veto and enacting the “9/11 Victim’s Bill,” Congress created a variety of potential problem for the U.S.

It is difficult to believe that 15 years have already passed since 26 al-Queda terrorists hijacked four passenger jets and forever shattered any sense of security still held by American citizens. Since that time, many people have tried to put the pieces back together and carry on with their lives. Yet a recent bill passed into law threatens to not only pick away the scabs of old wounds, it also presents a Pandora’s Box of potential problems.

[T]his bill presents a slippery slope with potential consequences that Congress neither understood nor contemplated.

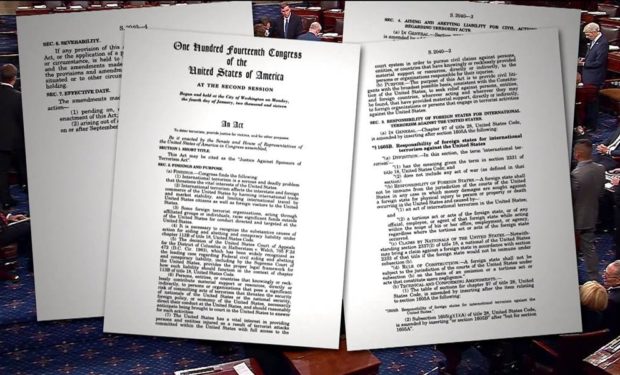

Congress sent the “Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act,” (JSTA) – which has been dubbed the “9/11 Victim’s Bill” – to President Obama to sign on September 9, 2016. This bill, fraught with controversy, was intended to allow the families of those lost in the 9/11 terrorist attacks to sue the Saudi Arabian government for any involvement in the planning and execution of those attacks.

President Obama was a vocal critic of the JSTA, vowing to veto it. “I have deep sympathy for the families of the victims of the terrorist attacks of [9/11]. I also have a deep appreciation of these families’ desire to pursue justice and am strongly committed to assisting them in their efforts,” the President said in his veto message. Nevertheless, President Obama believed that the best course of action was through other means that would not potentially open U.S. military and diplomatic leaders to potential repercussion lawsuits around the world. On September 23, the President kept his vow and rejected the bill.

Congress was expected to override the President’s veto, and did so on September 28. The vote in favor of the override was overwhelming and overwhelmingly bi-partisan: 97 senators and 348 representatives raised their hands in opposition of Obama. This marked the first time in two terms that President Obama’s veto was overridden.

In response to the override, President Obama accused Congress of passing the JSTA in order to garner votes. He told CNN, “I think it was a mistake, and I understand why it happened… [If] you’re perceived as voting against 9/11 families right before an election, not surprisingly, that’s a hard vote for people to take. But it would have been the right thing to do.” He warned that this bill presents a slippery slope with potential consequences that Congress neither understood nor contemplated.

Congress has essentially reduced the degree of sovereign immunity afforded to foreign countries.

In its findings justifying the JSTA, Congress cited, inter alia, the effect of international terrorism on interstate and foreign commerce, the need to protect citizens of the United States against those who support terrorism, and a need to provide legal remedies to those harmed by such supporters. In fact, the very purpose listed by Congress for the JSTA is to “provide civil litigants with the broadest possible basis…to seek relief against persons, entities, and foreign countries, wherever acting and wherever they may be found, that have provided material support…to foreign organizations or persons that engage in terrorist activities against the United States.”

To achieve this, Congress has essentially reduced the degree of sovereign immunity afforded to foreign countries. Sovereign immunity is a legal theory which states that a sovereign (i.e., government) cannot be sued unless it gives its consent. The American concept of this idea hails from English common law, which held that the king (sovereign) could do no wrong, and therefore could not be held to answer for any wrongs unless he agreed to be so held. This idea was adopted and applied to the sovereign government early on in the United States, and is cemented in American jurisprudence through several precedents and Congressional acts.

Among these acts was the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 (FSIA). This FSIA was passed in an attempt to provide clear guidance for resolving questions about immunity of foreign nations in U.S. courts, as well as to reduce diplomatic and political tensions that may cloud the process of answering these questions. Essentially, the FSIA gives a fairly broad grant of sovereign immunity to foreign states, rendering them immune from being civilly sued in any U.S. state or federal court. The FSIA contains several exceptions to sovereign immunity, such as the defendant nation being designated as a state-sponsor of terrorism at the time the act giving rise to the action occurred.

According to the act, it does not matter where – or even in what country – the foreign state or agent committed the tortious act.

The language of the 9/11 Victims Bill expands on the language of the FSIA. Subsection (b) of what has been codified as 28 U.S.C. § 1605B reads:

A foreign state shall not be immune from the jurisdiction of the courts of the United States in any case in which money damages are sought against a foreign state for physical injury to person or property or death occurring in the United States and caused by…an act of international terrorism in the United States and a tortious act or acts of the foreign state, or of any official, employee, or agent of that foreign state while acting within the scope of his or her office, employment, or agency, regardless where the tortious act or acts of the foreign state occurred. (emphasis added).

In summary, this law allows those harmed (or the families of those killed) to sue a foreign state for money if the harm or death was caused by an intentional act of terrorism within the United States. Additionally, the foreign state or its agent must commit a tortious act which contributes or assists in facilitating that terrorist act. According to the Act, it does not matter where – or even in what country – the foreign state or agent committed the tortious act.

“Even if the plaintiffs win, all they get is a piece of paper saying ‘yes, we agree with you, congratulations.’.”

There is a subtle provision in the JSTA which could still create obstacles for any lawsuits to actually gain traction. Section 5 of the JSTA allows the Attorney General of the United States to intervene and seek an order to put cases on hold or to stay any judgments as long as the U.S. is “engaged in good faith discussions with the foreign state defendant concerning the resolution of the claims” against them. This effectively puts the matter into the Executive’s hands – possibly into perpetuity, depending on politics.

Additionally, as Stephen Vladek, professor at the University of Texas School of Law, noted, the legislation does not allow any claims based on indirect support of terror, nor does the law give U.S. courts any authority to seize foreign assets. He pointed out, “Even if the plaintiffs win, all they get is a piece of paper saying ‘yes, we agree with you, congratulations.’.”

The potential fallout from the bill’s passage has yet to be realized.

The potential fallout from the bill’s passage has yet to be realized. Within hours of its passage, over two dozen senators signaled regret for their votes. Some cited lawsuits in foreign countries which the U.S. may become party to as a result of military or intelligence activities. Indeed, Secretary of Defense Ash Carter has voiced concerns that the JSTA would result in “an intrusive discovery process” resulting in the public disclosure of classified information.

There are also concerns about economic fallout. While American courts could seize foreign-owned assets within the U.S., those same foreign countries could sell those assets if they foresee a lawsuit. Such actions may cause more harm to the economies of the foreign nations more than they may harm the U.S. economy.

Finally, there are repercussions to consider. President Obama cautioned that the U.S. relies on the doctrines of sovereign immunity to prevent foreign tribunals from questioning America’s counterterrorism efforts. If foreign countries began their own reciprocal lawsuits, U.S. military members and diplomats may also be subjected to litigation. As the President wrote, the U.S. has “a larger international presence, by far, than any other country [and is] active in a lot more places than any other country, including Saudi Arabia.”

Adam Ereli, a former State Department spokesman and former ambassador to Bahrain, said, “Certainly this bill doesn’t win America any friends.” While he notes that the bill fails to account for foreign policy or national security, he does not believe that Saudi Arabia or any other Gulf Arab countries will try to bring their own lawsuits against the U.S. because of their cooperation with America in its counterterrorism efforts. “They can’t turn around and say we want to try you for war crimes because it would be like accusing yourself,” he told Business Insider.

Time will tell how this plays out.