A close call: D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals strikes down prison call regulations

Despite the high price many inmates pay for a simple phone call, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit recently found the FCC’s attempts to regulate phone call prices exceeded its authority.

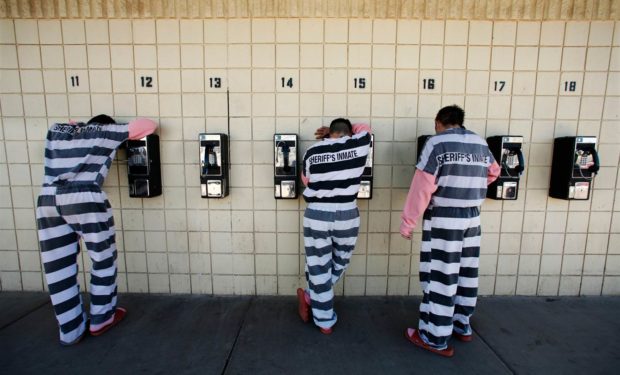

How much would you be willing to pay for a simple phone call to a friend or family member? $1.50 per minute is an extraordinarily high rate for an in-state phone call, but for millions of Americans with an incarcerated friend or family member, it is a price they are willing to pay to speak to their loved ones. In fact, as high as $1.50 per minute is the price that has been paid to make phone calls to in-state inmates, according to Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. Federal Communications Commissioner Mignon Clyburn has called the climbing price rates of prison and jail phone calls a civil rights issue, and her agency, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), has been working to regulate the high prices of these types of calls since 2013. But in a recent decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit struck down a significant portion of the FCC’s attempts to regulate inmate call prices.

Telephone services in prisons and jails are provided by private companies which contract with various institutions to provide the services. As a result, the inmate’s choice of service provider is limited to whatever provider has contracted with that institution. An inmate’s options are further limited to making either collect calls, pre-paid calls, or calls paid for from a debit account that the inmate or inmate’s family funds. In addition to the limited options that inmates have, the current state of prison and jail telephone services is problematic because of the fact that the contracts to provide services are exclusive and, typically, the institution receives a portion of the revenue from the inmates’ calls.

Capping the rates of prison call prices is not a new idea. The path to prison phone call price regulation began with a petition to the FCC by Martha Wright-Reid, a retired nurse whose grandson was incarcerated in Arizona. Martha was spending over $100 each month just to speak with her grandson over the phone. At first, federal regulators sought to cap the price rates of only interstate phone calls from incarcerated people. Most recently, in August of 2016, those caps were expanded to also cover intra-state prison or jail phone calls. Additionally, the FCC regulations prohibited certain types of fees that could be charged by the service provider, capped the rates of allowable fees, and capped fees that service providers could charge for accessibility services, such as TTY—a service which converts phone conversations into text for the deaf and hard of hearing.

These high costs are particularly problematic for low-income families wishing to stay in touch with their incarcerated loved ones.

There are many moral, social, and economic motivations behind the regulation of prison and jail telephone service price rates. First, the high prices of inmate calls prevent many of the 2.7 million children in America with at least one incarcerated parent from speaking by phone with their parents. These high costs are particularly problematic for low-income families wishing to stay in touch with their incarcerated loved ones. Some believe that the high price rates of inmate calls creates a Finally, with respect to the economic motivations behind the regulations, some, like Commissioner Clyburn, believe there exists a market failure regarding inmate phone call services. This market failure is thought to be due to a lack of competition fostered by the current system of service providers negotiating exclusive contracts with institutions and sharing in the revenues.

Not everyone favors inmate call regulation. Major telephone service providers, led by CenturyLink, Securus Technologies, and Global Tel Link, along with a host of state and local law enforcement agencies filed suit challenging the new regulations. They argue that the FCC exceeded its authority in placing the caps on call price rates and in implementing other related regulations. Telecom companies, like Global Tel Link, prefer market-based solutions to alleviate the high costs of inmate calls. Additionally, the telephone service providers claim that the high rates for inmate calls are necessary to provide the service securely and still stay afloat; however, FCC filings estimate that inmate calls often cost less than five cents to be transmitted. State and local law enforcement are concerned that the caps will lead to a decrease in revenue from the inmates’ calls—revenue that the government and institutions depend on to pay for things such as employee salaries and benefits or inmate programs like addiction counseling. But in some cases, according to FCC filings, the revenues are simply contributed to the states’ general funds.

Following his inauguration in early 2017, President appointed a new Chair of the FCC, then Commissioner Ajit Pai. Under new leadership and a change in the composition of the Commission, the FCC declined to continue defending its prison call regulations in court. In a letter to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, counsel for the FCC advised the Court that a majority of the Commission did not believe that the FCC had the authority to cap rates on intra-state calls. With the current FCC no longer defending the Obama-era regulations–in particular those regulating intra-state calls–private attorney Andrew Schwartzman, who represents various inmate advocacy groups, stepped up to defend the regulations.

The FCC’s regulations exceeded the statutory authority granted to it by Congress when it attempted to regulate intra-state telecommunications, which is an area of regulation usually reserved to the States.

After hearing arguments in February, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals decided, in a 2-1 decision, that the FCC’s attempt to regulate intra-state prison and jail phone calls did exceed the authority of the FCC. In its opinion, the court took note that the current price rates were far too high, but the decision was based on the interpretation of federal law granting and limiting the authority of the FCC. The FCC’s regulations exceeded the statutory authority granted to it by Congress when it attempted to regulate intra-state telecommunications, which is an area of regulation usually reserved to the States. While the Court struck down the regulations pertaining to intra-state inmate calls, those pertaining to inter-state phone calls were left standing. It is important to note that, according to advocates of the regulations, an estimated 80% of all inmate calls are made intra-state, and now cannot be regulated by the FCC.

Reactions to the Court’s holding varied. Mr. Pai said in a statement following the Court’s decision that the Court had agreed with his position that the regulation of intra-state phone calls exceeded the FCC’s authority. Global Tel Link commended the Court’s ruling, but, like Mr. Pai, said it was committed to market-based solutions to decreasing the high price rates of inmate calls. CenturyLink merely called the outcome the “correct ruling.” On the other hand, Commissioner Clyburn, who led the FCC’s effort to regulate all inter-state and intra-state inmate phone calls, described the entire situation as “the greatest form of regulatory injustice I have seen in my 18 years as a regulator” and called the ruling “deeply disappointing,” but said, “we will press on.” Mr. Schwartzman described the ruling as “very

For proponents of inmate call regulation, there is still some hope. At the moment, it is unclear if the decision will be appealed and argued in the U.S. Supreme Court. For now, there is nothing stopping individual states from placing pricing regulations on inmate phone calls as Mississippi, New Jersey, and New York have done. And though Chairman Pai did not support the Obama era FCC regulations which capped price rates of prison phone calls in his former time as a commissioner, he has said he will work with Congress and other Commissioners moving forward to address high prices of prison phone calls “in a lawful manner.”