Earlier this year, the North Carolina General Assembly passed a bill that Gov. Pat McCrory called “unnecessary.” But this “unnecessary” bill, entitled the Family, Faith, and Freedom Protection Act, has garnered global attention and fanned the flame of a contentious constitutional debate that is spreading across the nation like wildfire.

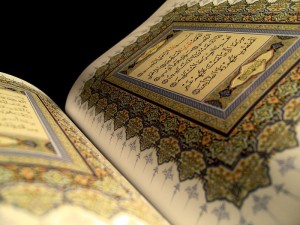

The bill, commonly referred to as the “Sharia law bill,” was introduced to protect fundamental constitutional rights from foreign laws that are at odds with the United States Constitution. While the North Carolina legislation does not explicitly target the Islamic legal system, its connection with the anti-Sharia movement is a strong indication that the name fits the bill.

The anti-Sharia movement attempts to prevent Sharia law principles—some of which violate fundamental rights and liberties protected by the United States Constitution—from entering the American court system.

The anti-Sharia law movement began seven years ago when lawyer David Yerushalmi began pushing his interpretations of Sharia law into mainstream discourse. The movement spawned what is known as American Laws for American Courts (ALAC), a model legislation crafted by Yerushalmi to protect American’s constitutional rights against the infiltration of Islamic legal doctrines. Versions of ALAC have been enacted in Kansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee and Arizona. In 2011 and 2012, sixty-two bills or amendments were introduced in twenty-nine different states that contained language inspired by Yerushalmi’s ALAC model legislation.

The anti-Sharia law movement began seven years ago when lawyer David Yerushalmi began pushing his interpretations of Sharia law into mainstream discourse. The movement spawned what is known as American Laws for American Courts (ALAC), a model legislation crafted by Yerushalmi to protect American’s constitutional rights against the infiltration of Islamic legal doctrines. Versions of ALAC have been enacted in Kansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee and Arizona. In 2011 and 2012, sixty-two bills or amendments were introduced in twenty-nine different states that contained language inspired by Yerushalmi’s ALAC model legislation.

Though Yerushalmi lacks formal training in Islamic law, his interpretations and opinions of Sharia have been widely disseminated as support for anti-Sharia legislation. His anti-Sharia sentiment is best expressed in Sharia Law and the American Court System: An Assessment of State and Appellate Court Cases, which was published by the Center for Security Policy (CSP). The article seeks to reveal Sharia law’s presence in American jurisprudence by case analysis and advocate for the enactment of ALAC legislation.

While CSP acknowledged the value of an academic approach to the study of Sharia law, it rejected outright an application of the legal system in American courts. The organization’s stated goal is to prevent Sharia law principles—some of which violate fundamental rights and liberties protected by the United States Constitution—from entering the American court system.

The case study contained in the article was conducted by Yerushalmi, CSP staff, and ACT! For America volunteers. The article identified a list of twenty state court decisions, found through a Google Scholar search, in which Sharia law was either applicable or at odds with the state’s public policy.

One case that the article highlights is S.D. v. M.J.R (pdf). The parties to the suit (husband and wife) were both Muslims and citizens of Morocco residing in New Jersey. The husband physically abused the wife and engaged in non-consensual sex with her. The trial court refused to grant a restraining order against the husband. The court held that although the husband had assaulted his wife, the husband’s belief that it was his religious right to do so precluded any criminal intent on the part of the husband. Soon thereafter, the appellate court rejected the husband’s defense and reversed the trial court’s decision. CSP seeks to prevent rulings at the trial level that recognize Sharia law when doing so would violate an individual’s constitutional rights.

Of the twenty cases discussed in the article, principles of Sharia law were rejected either on the trial or appellate level in all but seven cases.

It is true that versions of the Sharia conflict with American constitutional values; however, the article appears to disregard that other, non-radical interpretations of the Koran exist in the global Muslim community. In turn, the CSP and ALAC model legislation seek to exclude the Sharia law system as a whole from recognition in state courts.

Of the twenty cases discussed in the article, which span across twenty-five years, principles of Sharia law were rejected either on the trial or appellate level in all but seven cases. Such feeble evidence of Sharia law’s influence on state courts, critics state, does little to prove the necessity of bans on foreign law to safeguard Constitutional principles. Likewise, critics of the North Carolina legislation have called the bill a “solution without a problem.”

The CSP believes otherwise. Based on their interpretation of Sharia doctrine, the Sharia supports compliance with existing laws of a host country “only when Muslims have no choice.” The article comes to the conclusion a law such as the ALAC model legislation is needed to prevent the application of a legal system that does not afford the same liberties and protections as the U.S. Constitution.

Though provisions of Sharia law legislation differ from state to state, the Center for American Progress has identified a number of legal uncertainties and practical concerns (pdf) that may arise if the laws are afforded a broad interpretation.

Bans on foreign laws may undermine certain protections and rights afforded by the marriage system of the country where the marriage was performed.

Marriages and divorces that are performed and valid abroad are generally presumed to be binding in the United States. When the legality of these arrangements comes into question, the disputes are typically litigated in state family courts. For example, in North Carolina, “validity of a marriage is determined by the law of the state with the most significant relationship to the spouses and the marriage and that a marriage that is valid where contracted is valid everywhere.” However, marriages that are prohibited by North Carolina law and public policy will not be recognized although they were valid where performed. [ref] 1. 2 N.C. Family Law Practice § 16:3 [/ref]

Legislative bans on foreign laws may disrupt established practices of North Carolina’s family law courts. Under the new legislation, state courts may be restricted from recognizing foreign marriages when they are formed under a legal system such as Sharia law, even though a particular marriage arrangement would traditionally have been recognized as valid. For example, the validity of foreign marriages could be challenged on the basis that the legal system of the country where the marriage was formed is at odds with the state’s law.

Legislative bans on foreign laws may disrupt established practices of North Carolina’s family law courts. Under the new legislation, state courts may be restricted from recognizing foreign marriages when they are formed under a legal system such as Sharia law, even though a particular marriage arrangement would traditionally have been recognized as valid. For example, the validity of foreign marriages could be challenged on the basis that the legal system of the country where the marriage was formed is at odds with the state’s law.

Setting the Sharia law conflict aside, foreign law legislation may create complications for other religions. For example, the difficulties that Jewish women may experience in obtaining a divorce under Jewish law could lead the courts to invalidate the governing foreign law on the basis that it violates the notion of equal rights.

Bans on foreign laws may also undermine certain protections and rights afforded by the marriage system of the country where the marriage was performed. Spouses could abuse the legislation by invalidating marriages and avoiding paying marital assets. In the same vein, a court may refuse to enforce prenuptial agreements that were formed under a foreign or religious marital system that is perceived to be in conflict with American fundamental liberties. For example, in Soleimani v. Soleimani (pdf) a Kansas trial court stated that enforcing a mahr agreement would create an “obvious tension between the Establishment and Equal Protection Clause under the federal constitution” because such agreements “stem from jurisdictions that do not separate church and state.”

Legislative bans that are broad in scope would require an enforcing court to analyze the religious system to decide on the fairness in a particular case, rather than the relevant legal provision.

Decisions emanating from religious arbitration tribunals will face similar challenges of enforcement in states banning foreign law. Religious arbitration tribunals, which are often used to reconcile family disputes, may also be hindered by foreign law bans. Such arbitrations require a valid agreement to arbitrate. The parties choose the religious law that will govern (pdf) and the religious authority that will preside as the arbitrator.

Of course, state courts will not recognize such arbitration agreements or enforce decisions that are discriminatory or unconscionable. However, legislative bans that are broad in scope would require an enforcing court to analyze the religious system as a whole to decide on the fairness in a particular case, rather than the relevant legal provision. In effect, the evaluation of religious systems as worthy or unworthy of recognition would be required. Such an evaluation would violate the constitutional command that courts remain religiously neutral.

Additionally, the foreign law bans have the potential to undermine the Full Faith and Credit Clause, make the enforcement of arbitration awards nearly impossible, and violate the separation of powers.

North Carolina’s Family, Faith, and Freedom Protection Act is not quite as broad as ALAC inspired legislation in states like Kansas. The language of the bill attempts to limit the bill’s application to “only actual or foreseeable violations of fundamental rights resulting from the application of foreign law.” How this law will change the state court’s application and analysis of foreign law, if at all, is yet to be seen.

The discriminatory motivation of ALAC inspired legislation leaves the door open for constitutional challenges.

Even though there are no specific references to Islam, it is evident that the North Carolina bill was meant to restrict the recognition of Sharia law in state courts. The foreign law bill introduced in North Carolina has been criticized by national media outlets and by civic groups for being discriminatory in nature. Various Islamic interest groups have responded that the bill, while not explicitly directed at Muslims, was introduced for the purpose of singling out the Islamic Sharia law tradition.

The North Carolina ban has yet to be scrutinized under the First Amendment and Equal Protection clause of the U.S. Constitution. While North Carolina legislators drafted the legislation conservatively, the discriminatory motivation of ALAC inspired legislation leaves the door open for constitutional challenges, even if the bill’s language attempts to distance the bill from anti-Sharia law origins. As stated in the Center for American Progress report, much will depend on how North Carolina courts apply the law and whether the discriminatory flavors of the legislation are tasted in the ban’s application.

The Family, Faith, and Freedom Protection Act’s constitutionality will undoubtedly be called into question.

There are many uncertainties that surround the Family, Faith, and Freedom Protection Act. The anti-Sharia movement’s influence on similar legislation nationwide has cast shadows on the new legislation, and its constitutionality will undoubtedly be called into question. Moreover, it is not entirely clear how the North Carolina bill will affect the judicial decision making process. If the new law does change the court’s treatment of certain cases, then the process of analyzing the legality of matters such as foreign marital arrangements will stray from past practice.

In all, the Family, Faith, and Freedom Protection Act is confusing, redundant, controversial, and—as Gov. McCrory stated—unnecessary.