Brother, may I?: Saudi Arabia’s male guardianship system

Women in Saudi Arabia are denied basic human rights under a system that employs strict restrictions on everything from driving, to making healthcare decisions.

Imagine if the ability to exercise some basic human rights were conditioned upon permission granted by a male relative. This is a reality for Saudi Arabian women who live under the country’s male guardianship system. In Saudi Arabia, women are treated similarly to minors with respect to making major life decisions concerning education, travel, healthcare, and other activities which most of the world regards as fundamental human rights. In response to Saudi Arabia’s failure to comply with international standards of human rights, Saudi Arabian women have resorted to social media as a platform to challenge the guardianship system and advocate for enhanced rights for women in their country.

Transferring guardianship can be near impossible; women have little to no say in who their guardian is, and a woman’s husband retains guardianship throughout all divorce proceedings until the divorce is finalized.

Every woman in Saudi Arabia must defer to a male guardian to make major decisions for her entire life. In a recent article concerning the male guardianship system in Saudi Arabia, CNN stated, “A woman’s fate, regardless of her socioeconomic status, rests in the hands of her guardian, rendering adult women legal minors who cannot make decisions for themselves.” The male guardianship system is not codified in law but is a traditional cultural practice rooted in Islam and judicial interpretation of Sharia (Islamic law). As the official religion of the country, Islam provides the basis for the monarchist government of Saudi Arabia. The constitution and legal system are products of sharia, the Quran, and the Sunnah (life and tradition of the Prophet Muhammad). Support for the male guardianship system lends itself to some scholars’ and religious authorities’ interpretation of the Quranic verse, (4:34) “Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because God has given the one more [strength] than the other, and because they support them from their means.”

Under the guardianship system, male relatives serve as guardians. When a woman is born, her father is her guardian. When she marries, guardianship transfers to her husband. In the event of divorce or death of a guardian, the oldest male relative of the woman will serve as her guardian. This could be a brother, cousin, uncle, or even a son. Transferring guardianship can be near impossible; women have little to no say in who their guardian is, and a woman’s husband retains guardianship throughout all divorce proceedings until the divorce is finalized.

Travel restrictions also have serious implications for cases of domestic violence; a woman cannot flee an abusive domestic situation without permission to travel from her guardian, who is often times her abuser.

Once a guardian is established, he has control over many of the critical decisions a woman makes throughout her life. For example, male guardians have strict control over a woman’s right to travel. The Human Rights Watch reported that “women cannot apply for a passport or travel outside the country without guardian approval and women are barred from driving.” These restrictions on travel can seriously hamper a woman’s ability to seek and continue employment. Travel restrictions also have serious implications for cases of domestic violence; a woman cannot flee an abusive domestic situation without permission to travel from her guardian, who is often times her abuser. Though intrastate travel does not formally require guardian permission, the Ministry of Justice website lists complaints that can be filed electronically, including requests for a judicial order requiring a woman to return to the home of a male relative or husband.

Similarly, if a woman is imprisoned, she cannot be released without permission from her male guardian. A telephone interview conducted by the Human Rights Watch revealed that authorities “keep a woman in jail… until her legal guardian comes and gets her, even if he is the one who put her in jail” and that “if a family refuses to take a woman back to their home after she has finished her prison term, she must stay in prison or be transferred to a shelter.”

The Human Rights Watch reported that, “at some hospitals in Saudi Arabia, health officials require a guardian’s permission for women to be admitted or to undergo an operation.”

Until recent years, women required a guardian’s permission to work. Though no longer mandatory under the guardianship system, many employers still require guardian permission for women to work and the law does not punish employers who do so. In some cases, women must also receive guardian permission to access healthcare. The Human Rights Watch reported that, “at some hospitals in Saudi Arabia, health officials require a guardian’s permission for women to be admitted or to undergo an operation.” Additionally, women cannot marry without authorization from her guardian and the male guardian has to sign the marriage contract. Other legal transactions such as renting a home or filing legal claims can be very difficult for a woman to do without a guardian or male relative who is present and consenting.

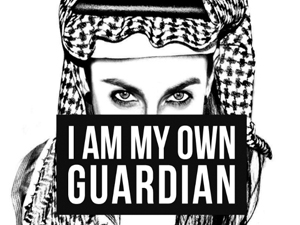

Women began tweeting their thoughts about, experiences with, and disapproval of the guardianship system followed by the hash tags #IAmMyOwnGuardian and #TogetherToEndMaleGuardianship.

The current campaign against the guardianship system began after the Human Rights Watch Report was issued in July, which described the guardianship system as “the most significant impediment to realizing women’s rights in the country.” The campaign started on Twitter. Women began tweeting their thoughts about, experiences with, and disapproval of the guardianship system followed by the hash tags #IAmMyOwnGuardian and #TogetherToEndMaleGuardianship. Some women have included pictures with written signs and symbols of their oppression. In their coverage of the twitter campaign, CNN included several tweets from Saudi women such as “Slavery comes in many shapes and forms: Male guardianship is one,” “I’m a prisoner and my crime is that I’m a Saudi woman,” and, “I can’t study, he said no.”

The campaign has since gained momentum worldwide and has received attention from Saudi Arabia’s senior and most influential religious authority, the Grand Mufti, who issued a statement in early September calling the campaign “crime targeting the Saudi and Muslim society” and supported the continued implementation of the guardianship system. CNN reported that, “the Arabic version of the hash tag [has] taken on a life of its own, with women across the country risking the wrath of their guardians, or even persecution.” Some Saudi Arabian women have started an opposition Twitter campaign with the hash tag “#TheGuardianshipIsForHerNotAgainstHer.” These women are advocating for the guardianship system to stay in place or for reformation of the current system.

“Women driving leads to many evils and negative consequences…[including] mixing with men without her being on her guard…Sharia prohibits all things that lead to vice. Women’s driving is one of the things that leads to that. This is well-known.”

Most recently, on September 26, an online petition signed by more than 14,000 women was presented to the Saudi government. The petition calls for a full end to the guardianship system. In addition to the petition, nearly 2,500 women flooded the office of King Salman, Saudi Arabia’s head of state and absolute monarch, presenting to him their own personal messages of support for the campaign. BBC reported there has been no official response to the petition yet.

In addition to pressures from Saudi citizens, the Saudi Arabian government is facing mass international pressure to abolish their male guardianship system.

This is not the first social media campaign demanding government action that Saudi Arabian women have led. Saudi women ran a campaign starting in 2011 to end the country’s prohibition on driving for women titled “Women2Drive.” As part of the campaign, women uploaded videos of themselves driving to social media. In response to the campaign, women were arrested, and as a condition of their release, they and their guardians had to sign a statement promising that they would not drive. The movement was met with great opposition from Saudi’s conservative religious government, and the Council of Senior Religious Scholars issued a fatwa (a religious decree) declaring, “Women driving leads to many evils and negative consequences… [including] mixing with men without her being on her guard… Sharia prohibits all things that lead to vice. Women’s driving is one of the things that leads to that. This is well-known.”

In addition to pressures from Saudi citizens, the Saudi Arabian government is facing mass international pressure to abolish their male guardianship system. In 2000, Saudi Arabia ratified the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which obliges Saudi Arabia to “to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating discrimination against women.” The Human Rights Watch reports “In 2009 and again in 2013, Saudi Arabia agreed to abolish the male guardianship system and all discrimination against women following its universal periodic review at the UN Human Rights Council.” The guardianship system, as well as other forms of discrimination against women present in Saudi Arabia, has caused the country to be categorized as “not free” according the reports from the Freedom House and the World Economic Forum, where Saudi Arabia ranked 134 out of 145 countries in their Gender Gap Index.

“…last year’s local elections were the first in the country’s history in which women were allowed to run as candidates and vote.”

Though the guardianship system is still largely in place, in the recent years, Saudi Arabia has seen some progress towards reforming the system and improving gender relations. The Human Rights Watch reported that “Saudi authorities removed restrictions on women’s work in the labor code, removed requirements for women to obtain guardian permission to work, and are actively encouraging women to enter the workforce.” Language was recently removed from labor laws that limited women’s potential occupation to fields “suitable to their nature.” While government actions have opened up the labor market to women, progress in this area is still limited by driving bans and strict sex segregation policies in the workplace, causing the World Economic Forum to rank Saudi Arabia 141 out of 145 countries in female labor force participation in 2015.

Also, CNN reports that “last year’s local elections were the first in the country’s history in which women were allowed to run as candidates and vote.” In 2013, King Abdullah appointed 30 female members to the Shura, the King’s advisory council, for the first time in Saudi Arabian history. Also last year, a small number of women were elected to municipal council positions. Despite these accomplishments, female political participation is still hindered by the male guardianship system. The numbers for female voter registration are low due to issues with proving residency due to the fact that women’s names seldom appear on deeds or leases.

Without the abolition of the male guardianship system, protecting victims of domestic violence is still limited due to restrictions on women’s ability to travel, initiate legal suits, and transfer guardians.

In 2015, The United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor reported that women in Saudi Arabia constitute over half of university students. Women in universities across Saudi Arabia are being offered scholarships to study abroad through the King Abdullah Scholarship Program, instituted in 2005. “Multiple women told Human Rights Watch that the scholarship program had been incredibly helpful in letting them pursue opportunities for higher education.” Due to the travel restrictions of the male guardianship system, a woman’s guardian has to give her permission to travel abroad to study under the scholarships and a male relative must accompany her.

In April 2016, Saudi Arabia announced Vision 2030, described as an “ambitious yet achievable blueprint” which includes an objective to “continue to develop [women’s] talents, invest in their productive capabilities and enable them to strengthen their future and contribute to the development of our society and economy.” It also stated that the goals of the plan is to “provide opportunities for everyone – men and women, young and old – so that they may contributed to the best of their abilities” and “to increase women’s participation in the workforce from 22 percent to 30 percent.”

The Human Rights Watch and the United Nations continue to propose policy recommendations, but true and genuine political change will only come about as a product of internal grassroots movements and systematic reforms compatible with Saudi Arabia’s political and religious traditions.

The country is also taking steps to better protect women against domestic violence. The Human Rights Watch reported that in “2013, [Saudi Arabia] passed a law criminalizing domestic abuse and in 2016, established a center specifically tasked with receiving and responding to reports of family violence.” Without the abolition of the male guardianship system, protecting victims of domestic violence is still limited due to restrictions on women’s ability to travel, initiate legal suits, and transfer guardians.

Ultimately, the Saudi Arabian government is showing signs of progress towards reducing the gender gap and reforming the male guardianship system. The Saudi Arabian women behind the current campaign show no sign of backing down, with one woman making the statement to CNN that it is “not going to stop unless the Saudi government abolishes male guardianship laws.” It is important to keep in mind that advocates behind the campaign are faced against a countervailing culture of religious conservatism deeply rooted in Islam, traditions of the theocratic monarchy, and entrenched discrimination throughout the country’s legal system. Saudi Arabia’s progress cannot reasonably be measured against that of westernized secular democracies. The Human Rights Watch and the United Nations continue to propose policy recommendations, but true and genuine political change will only come about as a product of internal grassroots movements and systematic reforms compatible with Saudi Arabia’s political and religious traditions. As they are gaining access to the work force, education sector, and political sphere, Saudi Arabian women remain hopeful. As Khadija, a 42-year-old Saudi woman told the Human Rights Watch, “It is amazing how much we have achieved despite all the restrictions we face… Now that more women are working, I think there will be further changes. It is inevitable.”