Crime does pay…the State

North Carolina’s “drug taxes” on substances ranging from marijuana to moonshine are reaping a major reward.

Most people know that it is illegal to possess certain drugs like marijuana and cocaine in the state of North Carolina. What many people do not realize, however, is that under North Carolina’s “unauthorized substances tax,” a person who possesses controlled or illicit substances must pay a tax to the state. This appears to be an odd law, to say the least. Essentially, North Carolina’s unauthorized substance tax law requires those who possess illegal substances like marijuana, cocaine, or moonshine to pay taxes on these items. North Carolina’s “Unauthorized Substances Tax” went into effect on January 1, 1990. In the 2015 fiscal year alone, North Carolina collected over $6 million in drug taxes.

Generally, drug dealers are not flocking to North Carolina’s Department of Revenue building to pay taxes on their newly acquired drug supply.

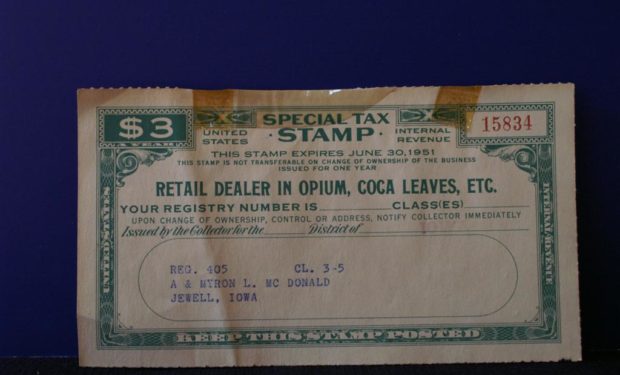

The “Unauthorized Substance Tax” has specific guidelines for enforcement that are defined in N.C.G.S. 105-113.107. The statute presumes that any individual in possession of a substance that falls under this tax is a drug dealer. In a nutshell, North Carolina charges $3.50 for each gram of marijuana, $50 for each gram of cocaine, $50 for each group of “low-street-value” drugs such as steroids, and $200 for each gram of a controlled substance. The law also prohibits the possession of “illicit spirituous liquor” (such as moonshine). Drug dealers are required to pay the tax within 48 hours of receiving the illegal substance, but the law does not require them to disclose their name, social security number, address, or any other information that may identify them. When the dealer pays the tax he or she will receive a “tax stamp” that should then be attached to the drugs. These stamps can be purchased either in person or by mail. A provision in the law also prohibits the Department of Revenue from revealing any information about the purchase of tax stamps to law enforcement. Tax stamp information cannot be used against drug dealers in court, or for the purpose of any investigation.

Generally, drug dealers are not flocking to North Carolina’s Department of Revenue building to pay taxes on their newly acquired drug supply. This raises a clear enforcement problem. In fact, according to Ron Starling, the former director of the Unauthorized Substance Division in North Carolina, only 77 people paid the tax in the first 14 years of its enactment. Therefore, North Carolina makes most of its money from this tax when an alleged drug dealer is arrested and drugs are confiscated without an attached tax stamp. When this occurs, North Carolina serves the alleged drug dealer with a tax bill, which includes the tax itself, plus penalties and interest. The dealer must then pay the tax bill or the state will take the dealer’s property to pay the bill.

Dealers do not actually have to be convicted of possession of an illegal drug in order to be charged the unauthorized substances tax.

When dealers are “picked up” on drug charges, and there is evidence that the drug tax has not been paid, the North Carolina Department of Revenue automatically sends a bill to that individual. This is sometimes ineffective because the bill is sent to the last known address of the dealer, which is typically an invalid address. Usually individuals who have been arrested and charged with a drug crime are more concerned with their defense than paying a drug tax. As a result, drug tax bills are often overlooked or ignored. By the time the dealer acknowledges the bill, and is able to pay, months or even years may have passed, at which point the cost of the tax is nothing compared to the cost of penalties.

The tax can be challenged within 45 days of receiving the bill. Some individuals retain a lawyer if they believe they have been wrongfully charged the tax. Other times, a “quick settlement” is an option. A quick settlement gives the Department of Revenue the power to settle the drug tax without requiring a formal process. Usually, a revenue officer will look at the dealer’s assets and work out a specific settlement. This settlement is typically an amount that will satisfy the tax and be realistic for the dealer to pay.

Dealers do not have to be convicted of possession of an illegal drug in order to be charged the unauthorized substances tax. Since the tax is a civil fee, and entirely separate from any criminal charges a dealer may face, dealers may still be obligated to pay the tax even if no criminal charges have been filed.

Although most drug tax laws are deemed to be constitutional, these laws have constantly come under scrutiny from the time of their existence.

Even though North Carolina has implemented this tax for over a decade, several questions have been raised as to the constitutionality of drug tax laws. The Fifth Amendment protects individuals against self-incrimination and double jeopardy. It also protects individuals from being “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” A tax on illegal substances may seem strange at first glance. How can a state tax and make a profit from items that are not recognized under law? The answer comes from a series of nine Supreme Court cases dating back to 1866. These cases established that Congress has the power to tax activities that are prohibited by law. The Supreme Court reasoned that the prohibition of the activity by law, coupled with the taxation, would serve as a large deterrent that would discourage illegal activity. After the Supreme Court set this precedent, states essentially became authorized to tax all illegal activities.

Generally, drug taxes are held to be constitutional because the tax is civil, not criminal. Therefore, if a dealer is convicted of a drug-related charge and then ordered to pay the tax, the Fifth Amendment is not violated because the dealer was only charged and punished once in criminal court. This satisfies the double-jeopardy requirement under the Fifth Amendment. Similarly, because tax stamps are purchased anonymously, without record, and cannot be used against the dealer in court, the Fifth Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination is satisfied. Further, drug tax laws are usually held to be constitutional because dealers are given an opportunity to pay the tax legally. When law enforcement officials confiscate drugs that do not bear a tax stamp, the drug tax can be freely applied, without violating the Fifth Amendment, because the dealer failed to obey the law of purchasing the tax stamp and placing it on the drugs.

Although most drug tax laws are deemed to be constitutional, these laws have been constantly under scrutiny from the time of their existence. In fact, North Carolina’s original “drug tax” law was deemed unconstitutional because of the rate of the tax was so high that it “crossed the line from tax to multiple punishments for the same offense.” The original law was also deemed unconstitutional because the tax was applied only after the dealer was arrested and the drugs were no longer in his or her possession. The law was revised in 1995 to limit the tax rate so that it would not exceed the “market value” of drugs and to require actual or constructive possession of the drugs before the tax could be applied.

North Carolina is not alone in implementing taxes on illegal substances. As of 2008, a total of thirty states had also enacted laws similar to North Carolina’s. Although on a yearly basis, North Carolina’s Department of Revenue handles about 5,000-6,000 cases of unpaid taxes on illegal substances, thus far, the department has only received approximately 106 requests for stamp orders, the majority of which has come from stamp collectors, not drug dealers.