DDoS attacks: the common cyber-weapons of choice

Though the number of small-scale “distributed denial of service” attacks has increased, the number of prosecutions for such attacks remains relatively low.

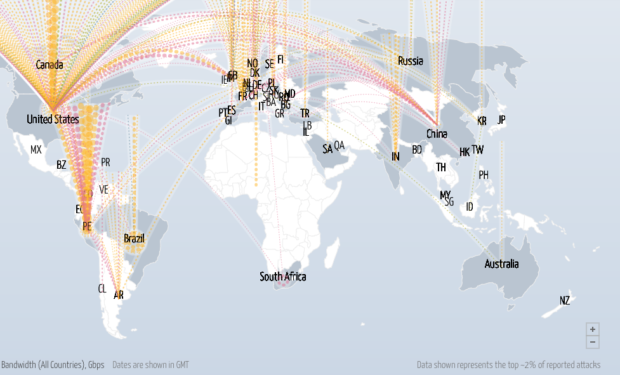

Image: An interactive map shows data from the infamous Dec. 25, 2014, DDoS attack on Microsoft and Sony, http://www.digitalattackmap.com/

Image: An interactive map shows data from the infamous Dec. 25, 2014, DDoS attack on Microsoft and Sony, http://www.digitalattackmap.com/

Business A has recently been exposed as having profited from foreign sweatshop labor and questionable trade practices. In the town over, Business B has established itself as a highly successful and competitive operation that is increasingly taking over the local market, albeit fairly. In the last town, Business C is a simple mom-and-pop shop with no notable qualities or distinguishing market advantage. Also in these towns are Activist A, Competitor B, and Joker C.

Each of these individuals decide to plan an attack on their respective business counterparts. The attackers each hire groups of 1,000 people to flood the doorways of these businesses to prevent legitimate customers from entering and doing business. Activist A attacks Business A in this manner as a form of peaceful protest, attempting to stifle the profits of an unfair and greedy corporation. Competitor B attacks Business B because he knows his business cannot compete with Business B without resorting to sabotage. Joker C attacks Business C because Joker C just wants to watch the world burn.

A denial of service attack is a cyber-attack in which the attacker attempts to prevent users from accessing certain information or services.

The hypothetical “attacks” above are realized, in one form or another, every day through denials of service (DoS). A denial of service attack is a cyber-attack in which the attacker attempts to prevent users from accessing certain information or services. This is typically done by “flooding” a computer or network with a large amount of information. Computers and networks can only handle so much of this traffic until they become overloaded and stop processing new requests. This can be likened to the hypotheticals above; like flooding a doorway with a large quantity of people to prevent entrance to the target business, a computer or network can be flooded with a large quantity of data to prevent access to the target website or service.

This flooding of information is typically done through a distributed denial of service attack (DDoS). Effective DDoS attacks require a sufficient quantity of traffic directed toward the target system. This can rarely be done with a single attacking system. With DDoS attacks, a user can employ what is known as a “botnet” to facilitate the flooding. These botnets are generally made up of a large number of individual computers that have been “infected” and essentially become “zombies.” Any personal computer can be the target of a malware scheme that intends to use the target computer as a zombie within its much larger botnet. When an attacker wants to commit a DDoS attack on some service or webpage, the attacker can effectively command the botnet, made up of the many zombies, to send large quantities of data to the target in a concentrated effort.

As demonstrated in the hypotheticals above, DDoS attacks can be used as tools for peaceful protest, competitive advantage, and random hijinks. In an interview with Joseph Cox of Motherboard, Molly Sauter, a research affiliate at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, explained that “DDoS has been around as an activist tactic probably since the early 90’s.” Sauter is the author of The Coming Swarm: DDOS Actions, Hacktivism, and Civil Disobedience on the Internet. In the book, Sauter tells the story of DDoS actions as a tool for protest and political activism. Sauter confirms that DDoS attacks are, indeed as simple as explained above at a purely technological level.

One of the most notable and recent large-scale attacks occurred on Christmas day of 2014. Those attacks targeted Microsoft and Sony, shutting down XBOX Live and PlayStation Network.

One of the most notable and recent large-scale attacks occurred on Christmas day of 2014. Those attacks targeted Microsoft and Sony, shutting down XBOX Live and PlayStation Network. The attackers, a group known as “Lizard Squad,” claimed the attacks were meant to highlight the incompetence of both Microsoft and Sony. The Daily Dot interviewed some of the members of Lizard Squad, who stated that “Microsoft and Sony are . . . literally monkeys behind a keyboard.” The group went on to state the ways in which Microsoft and Sony are both inept, yet make huge sums of money every year off people who must rely on the companies’ ability to keep their systems running.

In 2015, a member of Lizard Squad was found guilty of 50,700 charges related to computer crimes in Finland. Julius “Zeekill” Kivimaki was involved with the attacks that took down XBOX Live and PSN, but the charges in Finland were unrelated. Surpisingly, Kivimaki received no prison time, but instead was given a two-year suspended sentence, as well as ordered to fight cyber-crime.

These attacks occur on a much smaller, personal scale every day as well. Players in competitive, head-to-head online video games will target individual IP addresses and direct a small-scale DDoS attack toward that target, seeking to disconnect them from the game. Players in a small six-versus-six match can seek to eliminate one or two players on the opposing team by utilizing DDoS attacks, giving their own team a significant man advantage. Overwatch, one of the world’s most popular competitive video games, boasting 35-million players worldwide, is a frequent virtual arena for DDoS attacks directed at individuals. While these attacks rarely have any long-term effects, those caught perpetrating such attacks could face legal penalties.

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1030, is the primary federal law that applies to fraud and related activity in connection with computers. Much of the Act pertains to actions made against the United States government, but section (a)(5) contains language that covers DDoS attacks. Sections (a)(5)(A) applies to whoever “knowingly causes the transmission of a program, information, code, or command, and as a result of such conduct, intentionally causes damage without authorization, to a protected computer.” Further, subsection (a)(5)(B) applies to anyone who “intentionally accesses a protected computer without authorization, and as a result of such conduct, recklessly causes damage.” Finally, subsection (a)(5)(C) extends to anyone who “intentionally accesses a protected computer without authorization, and as a result of such conduct, causes damage and loss.” All three of these subsections are misdemeanors at their base level, but subsections (a)(5)(A) and (a)(5)(B) can increase to felony level if there is sufficient loss or other specified harms.

Not surprisingly, though, the vast majority of DDoS attacks go uncharged.

The first of the three subsections, which only requires proof of a “knowing transmission of data,” wisely reaches attackers who cannot be proven to have actually accessed a protected computer. As explained above, the use of a botnet to flood a target computer or system can lead to damage of the target system without the actual attacker accessing the target site themselves. It is also important to note that the “damage” element of this crime may be satisfied by acts that simply make computers or information unavailable, such as making an online game unavailable to other players.

Cases involving DDoS attacks are handled by the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section of the United States Department of Justice, which actually has a book to provide assistance. Not surprisingly, though, the vast majority of DDoS attacks go uncharged. While large attacks, like the one Lizard Group effectuated, will certainly be investigated due to the sheer magnitude of the attack, small-scale, individualized attacks, which are technical violations of the law, will typically not be.

Every day, mischievous gamers determined to gain an edge on the competition employ tactics to deny service to their competitors. It would not make sense, or perhaps be possible, to seek prosecution of every individual who violates the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. This lack of enforcement, though, incentivizes people to DDoS their competitors for personal gain. With no government watchdog to prevent or punish DDoS attacks at this smaller, more local level, it appears Microsoft and Sony, the so-called “monkeys behind the keyboard,” will just have to do their best.