Drug testing for Welfare recipients: as simple as it sounds?

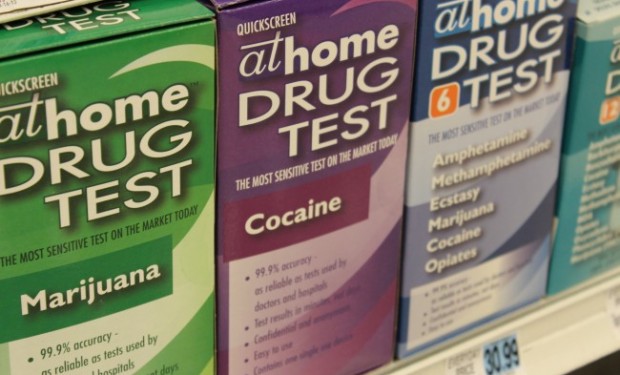

N.C. Senate Bill 594, which would mandate drug testing for all welfare beneficiaries and require the beneficiary to front the testing costs, is far from a simple “solution” to a quite complex issue.

Updated September 4, 2013: Following yesterday’s House vote overriding Gov. McCrory’s veto of House Bill 392, the Senate voted today to override the Governor’s veto by a 34-10 vote. Gov. McCrory has stated that he has no intention to carry out the newly passed law.

Updated August 15, 2013: House Bill 392, requiring similar screening of Work First program participants as the defunct SB 594 discussed below, was the subject of Gov. McCrory’s first veto today. Gov. McCrory stated that “Drug testing Work First applicants as directed in this bill could lead to inconsistent application across the state’s 100 counties. That’s a recipe for government overreach and unnecessary government intrusion.”

“The least they can do is get themselves clean, pass a drug test, get their money back,” said Senator Jerry Tillman (R-Randolph) of the welfare recipients at the heart of the debate over N.C. Senate Bill 594. “Seems to me that we’re complicating a pretty simple situation.”

As simple as the Senator makes it sound, the arguments surrounding the Bill—which would require a drug test in order to receive welfare benefits—are anything but. With the passing of the Bill in April 2013 by the North Carolina Senate, many have already begun debating the constitutional and fiscal implications as North Carolina citizens wait to see whether the requirement is eventually signed into law.

Once identified, the recipient will be referred to assessment by a professional and subsequent treatment for any substance abuse.

North Carolina families in need of government support can apply for the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, “Work First,” where they will receive lump-sum cash assistance to support themselves and their children. Currently, the law mandates social service agencies involved with Work First to identify recipients who may be drug and alcohol abusers. Once identified, the recipient will be referred to assessment by a professional and subsequent treatment for any substance abuse. The Bill, if signed into active law, will instead compel a mandatory drug test for all adults applying to the program. The state would also require recipients to front the costs for the required drug test, reimbursing the recipient only if he or she passes.

Proponents of the law are wary that the current practice of giving out lump sums of cash to substance-abusing welfare recipients will fuel the state’s illegal drug market. This would not only waste money, but would also go directly against Work First’s mission by hindering the likelihood that the recipient is working toward self-sustaining practices, such as searching for a job. During the floor debate, Senator Ralph Hise (R-Mitchell) asserted, “We have to be aware of how we are creating and [how] we are funding this problem in our communities.”

Opponents of the Bill question whether an impoverished person’s need for government assistance necessarily gives rise to drug suspicion.

While senators on both sides of the issue are undoubtedly concerned with ridding our state of drugs, the “blanket” requirement has numerous legislators and civil rights activists up in arms, many declaring it to be a violation of the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Similar laws in Michigan and Florida mandating drug tests have been declared unconstitutional as unreasonable searches under the Fourth Amendment.

Defining what is “unreasonable” in the context of a Fourth Amendment violation often centers on whether there was the adequate level of suspicion for the search or seizure. The question from which tempers flare in the current debate: is the need for Work First assistance suspicion enough to warrant a drug test?

Critics of these laws often cite findings that indicate that welfare recipients are no more likely to abuse drugs than the rest of the population. The Florida District Court ordered a temporary injunction on the law under the same reasoning, noting that the State’s argument “rest[s] on the presumption of drug use” but that “there is nothing inherent to the condition of being impoverished that supports the conclusion that there is a ‘concrete danger’ that impoverished individuals are prone to drug use.”

The studies regarding the prevalence of drug use among welfare recipients, however, seem to go both ways. Most of the data relied upon by legislators and activists, both for and against these laws alike, is either over a decade old or too indeterminate to have any real teeth.

“Either drugs do have an impact on productivity, unemployment and absenteeism, and the condition of a drug search is germane, or they do not have such impacts and are not germane.”

Ilan Wurman, a Stanford Law graduate, argued in a recent article for Jurist that regardless of whether a court could find adequate proof of cause to require recipients to submit to drug testing, the welfare drug-testing laws could be struck down under another doctrine: unconstitutional conditions. The doctrine mandates that the government may not condition providing a governmental benefit to someone on that person’s waiver of a constitutionally protected liberty.

Here, the act of compelling a drug test in order to receive welfare may be a constitutional condition—one that is permitted. Acceptable constitutional conditions, however, must be germane to the benefit being provided by the government. In defining the connection between the condition and the benefit, Wurman asks, “is the reason the government attaches the condition a reason for which it might refuse to offer the benefit altogether?”

For Wurman, it is clear that the answer is yes. The discretionary benefit provided by the government is furthered by and related to the compelled drug test, and therefore falls under the category of acceptable constitutional conditions. He says you can only come to one of two conclusions in the inquiry: “Either drugs do have an impact on productivity, unemployment and absenteeism, and the condition of a drug search is germane, or they do not have such impacts and are not germane. But if one adopts the latter position, one must also question why drug use is illegal at all.”

“You’d have to be pretty high to spend your own money to take a test that you know you would fail.”

Bypassing the obvious constitutional hurdles for a moment, many wonder if passing the Bill into law would be a fiscal money-pit for the state. A second major point of dispute surrounding the Bill is the fact that it requires Work First applicants to pay for their own drug tests (about fifty dollars)—at least at first. If the applicant passes the drug test, he or she would be reimbursed by the state; if not, benefits will be denied for at least a year or until the applicant undergoes a treatment program and then passes a retest.

As of yet, the government has not said exactly how the reimbursements will be funded. The Bill simply reads, “the Department [of Social Services] shall increase the amount of the initial Work First Program assistance by the amount paid by the applicant or recipient for the drug testing.” Opponents of the Bill note that drug-free welfare recipients having to pay for a test is not only humiliating but would also cost the state money that it does not have. Sarah Preston, Policy Director for ACLU of North Carolina, said that “all available evidence shows that North Carolina would lose more money than it would save under this proposal.”

The evidence she is referring to, however, rests largely on state-specific studies utilized in the Florida case. The ACLU reports that in Florida, only 2.6 percent of over 4,000 applicants failed drug screenings during the few months that the law was in place. Ms. Preston’s article, aimed at condemning Bill 594 and protecting North Carolina from what the ACLU regards as a disaster brought by the Florida law, goes on to report that as a result of the Florida law, “Floridians ended up paying more than $118,000 to reimburse applicants who passed the test, costing the government more than $45,000 more than the amount of aid that would have been given to people who failed their drug tests.”

At first glance, the numbers seem to speak for themselves. But as Senator Thom Goolsby (R-New Hanover) countered in the floor debate, “You’d have to be pretty high to spend your own money to take a test that you know you would fail.”

What Senator Goolsby was referring to is the fact that statistics such as the one cited by the ACLU seemingly skew the data, reasoning that of course only 2.6 percent of failed the drug test—why would anyone who has taken drugs pay out-of-pocket for a drug screening, knowing they will only receive benefits and be reimbursed for the test if they pass it? Senator Jim Davis (R-Macon) affirmed this position stating, “These people are sharp enough to understand– If you’re on drugs, you may want to consider delaying your application for benefits.”

The main goal was furthered – to keep taxpayers’ dollars out of the drug market.

Floridians who supported their version of the law stand firm in their efforts, noting that regardless of the fact that the law may appear to be a fiscal flop, the main goal was furthered – to keep taxpayers’ dollars out of the drug market. Many believe that had an injunction not been issued after only four months the state would have seen more savings, as the law’s supporters initially anticipated.

While the Florida and Michigan laws came to a halt before ever really gaining any traction, we have yet to see if North Carolina’s version will launch at all. Amid heavy constitutional concerns and unpromising examples set forth by other states, a mounting state debt will not allow for unpredictable ventures. The only sure conclusion is that this issue is by no means the “simple situation” that legislators such as Senator Tillman believe it to be.