EEOC Urges University of Denver Law School to Increase Female Law Professor Pay to comply with Equal Pay Act

The EEOC threatens to initiate a lawsuit against the University of Denver after discovering that the university’s male law professors were paid more than female law professors.

Earlier last month, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) determined that female law professors at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law were illegally paid less than men, in violation of the Equal Pay Act. The EEOC found that the pattern of unequal pay disparities for female law professors as opposed to their counterpart male law professors at the University of Denver was a “continuing pattern” dating back to 1973.

After this pay discrepancy was brought to the EEOC’s attention, the EEOC inquired into the pay scheme, and particularly the merit pay evaluations for law professors.

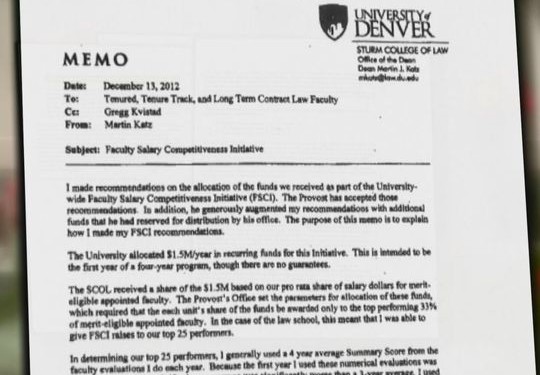

The EEOC discovered this gender pay gap and violation of the Equal Pay Act after a complaint filed by a law professor at the University of Denver, Lucy Marsh. Marsh’s salary was $109,000 annually in 2012, but was still considered the University’s lowest paid full time law professor. While employees typically do not discuss their salaries with other employees, Marsh was notified of this discrepancy in her pay as opposed to her male colleagues when the Law School Dean, Martin Katz, issued a memorandum discussing merit raises.

The memorandum sent by Dean Katz not only included the notification of potential merit raises, but it contained salary comparisons bringing to Marsh’s attention the discrepancy of salaries. The memorandum stated that female full time law professors were paid $16,000 less than their male colleagues on average. Rather than leaving the discrepancy at that, Katz further stated that there were several factors that came into play regarding the discrepancy, not sex-based. The “several factors” noted were differing merit raises and starting pays.

After this pay discrepancy was brought to the EEOC’s attention, the EEOC inquired into the pay scheme, and particularly the merit pay evaluations for law professors. The University Chancellor, Rebecca Chopp, stated that the “historical system” for evaluation and merit pay for law professors was based on professor ranks, duties, age, and performance scores. This evaluation was specifically reviewed by a consultant utilized by the university—no connection between pay and gender for the laws school was found.

The University Chancellor’s statement indicated that Marsh’s salary was lower due to her “substandard performance in scholarship, teaching and service.” However, Marsh states that she has won several teaching awards, and her Tribal Wills Project was recognized recently by the Denver Supreme Court.

… [T]he EEOC noted that the University knew about the gap in pay between male and female law professors since 2012 … and the University failed to take action on this realization.

After its investigation into the University of Denver’s law school and its pay schemes for male and female full time law professors, the EEOC notified the law school of its determination. In its findings, the EEOC noted that the University knew about the gap in pay between male and female law professors since at least 2012 when the memo from the Dean was issued, and the University failed to act on this realization. The EEOC further stated that the University’s failure to take action resulted essentially in a condoning and formalizing of a history of unequal pay for men and women in the legal education profession.

In order to comply with the Equal Pay Act and anti-discrimination laws, the university had to increase the wages of the female full time law professors and give them back pay for the lost wages they incurred by not being provided fair and equal pay. The EEOC threatened to initiate lawsuit over the discrepancy in pay between male and female law professors based on the “continuing pattern” of this gender pay gap at the University if they failed to comply with the back pay and increase in female law professor salaries. The University was not given a formula to utilize in determining back pay; that was left to the University’s discretion in order to comply with the EEOC’s advisement.

The University has expressed its contentment with the way the pay structure has operated historically. It is unclear whether the University will make changes to the pay structure to eliminate the discriminatory impact it has on female full time law professors, or whether the University will change the pay structure so as to prevent the discriminatory effect.

[The Equal Pay Act] states that men and women doing the same job at the same place are required to receive the same amount of money for the same work.

The Equal Pay Act, signed in 1963, was created to protect all workers, particularly female workers, from being treated unfairly and being given less pay than men with the same or similar qualifications for the same amount and type of work. The Act’s purpose is to “prohibit discrimination on account of sex in payment of wages by employers engaged in commerce or in the production of goods for commerce.” It states that men and women doing the same job at the same place are required to receive the same amount of money for the same work. The Equal Pay Act also creates the minimum wage requirement.

Essentially, when a pay structure is created that results in unequal pay between certain genders or races, for example, even if the discrimination is not intentional, the pay structure must be adjusted so as to avoid this disparate impact. Disparate impact discrimination is discrimination that results from an action or a requirement that has the effect of disqualifying a protected class of people or that excludes that protected class. When such a disparate impact is discovered, it must be remedied.

While the EEOC’s findings do not necessarily mean that there will be a lawsuit filed against the University of Denver’s law school, they do provide insight into how the Commission handles and treats instances of gender wage gaps. The EEOC’s findings here also provide guidance for other universities and employers on forms of improper pay schemes that may be utilized today.

While unintentional, [unequal pay schemes] are still not legal, and the fact that the pay scheme has been in existence for a particular period of time does not negate its discriminatory effect.

What effect does this finding in Denver have on other states, universities, and other employers across the nation? This case shows that the EEOC is prepared to take action against various pay schemes that have such a disparate impact with regard to the pay received by men and women. To this day, there are still gender pay discrepancies, and sometimes these discrepancies are in fact unintentional. While unintentional, they are still not legal, and the fact that the pay scheme has been in existence for a particular period of time does not negate its discriminatory effect.

It appears there is a trend in the realm of labor and employment law cases. More and more we see discrimination cases come up, but lately there have been many instances of challenges to pay structures and payment generally for work. We see here an Equal Pay Act challenge based on a pay structure resulting in a disparate impact on female full time law professors. In other cases we see challenges arising from unpaid interns claiming they are deserving of payment, or student athletes claiming they are entitled to payment for their service to the University. Similarly, we see more challenges to payment structures for hourly workers who claim to be misclassified.

While these cases may all appear to be very different, they are in fact quite similar in their effect. These cases present an interesting trend, where workers are beginning to become more aware of their rights and the law surrounding their payments and reimbursements. As such, employers may take this opportunity to do internal audits of their pay structures, what they are paying their workers, and check for anything that might resemble pay discrepancies. If such a payment scheme is found to have such a disparate impact on a particular protected class of workers, the employer can take the chance to change the payment structure and adjust in a way that will provide those employees proper payment, and prevent lawsuits.