Hurricanes hit harder for those with disabilities

Individuals with disabilities are uniquely vulnerable during natural disasters, and often do not receive adequate assistance in the aftermath.

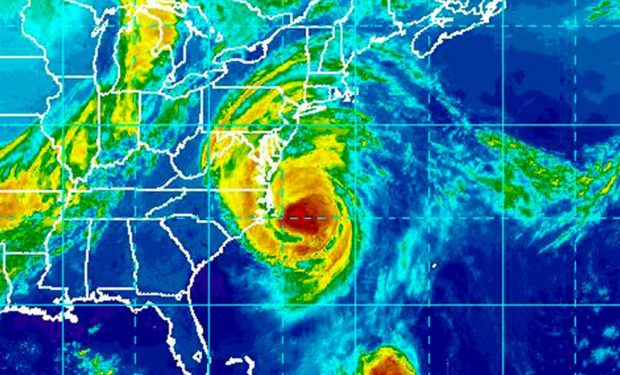

The 2017 season was predicted to be busy, and it exceeded expectations. Three major category four hurricanes stuck the United States in a little over three weeks. A category four hurricane has sustained winds between 130 and 156 mph. (In comparison, winds 65 to 70 mph will knock down a person who is standing still.) Hurricane Harvey swept into Texas on August 25, 2017, Hurricane Irma collided with the Florida Keys on September 10, 2017, and Hurricane Maria destroyed most of the infrastructure of Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017. The Southeast has been scrambling and emergency plans are being put to the test. People with disabilities are struggling to regain services and accommodations that enable them to maintain health and to live independently.

North Carolina residents with disabilities are still awaiting full restoration of their services and benefits following Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

In North Carolina, only days after a 10-inch rain event saturated the soil of the Piedmont, Hurricane Matthew brought another 15 inches of rain to the region. Most of the water runoff drained through Eastern N.C. along the Lumber, Neuse, Tar, and Black river corridors on its way to the Atlantic. This resulted in catastrophic flooding that displaced thousands of people. Initial estimates projected over $1.5 billion in property damage to over 100,000 homes.

In June 2017, over nine months after Hurricane Matthew made landfall, Iris Green, a senior attorney at Disability Rights North Carolina, was at a meeting in Robeson County assisting people with disabilities who remained displaced as the result of the storm’s unprecedented destruction. Mrs. Green wondered how advocates for people with disabilities could get a seat at the table during future emergency planning.

There are many common challenges that individuals with disabilities face when they are displaced from their communities. Children forced to relocate and enroll in new schools often lose services and specialized curriculum under their Individual Education Plans and 504 Plans. Many people receive medications through the mail and are not able to get them rerouted on short notice. In-home health aid services may be discontinued.

Similarly, many will miss medical appointments and routine procedures, as well as lose access to essential medical and rehabilitative services like occupational therapy and physical therapy. Once discontinued, it can be a time-intensive task to get services restarted under programs like Medicaid and many people will require assistance with that administrative task. Temporary housing is often inaccessible and suitable new permanent housing options sparse. Accessibility obstacles also extend to public transportation.

Local governments are at the forefront of emergency planning and response.

How does local government reach medically fragile people or people with disabilities who live at home, like those that Mrs. Green was called upon to assist? The most direct way is to establish a voluntary registry and ask residents to submit their information. This is the approach that Miami-Dade County has taken. The inclusive program in Florida, however, ran into difficulties during Hurricane Irma. The county created an Emergency and Evacuation Assistance Program whereby residents may register and give information about their medical needs or disability to the local emergency management agency.

In an emergency, residents are to be assigned to a shelter that can meet their needs and are to be provided with transportation assistance. In advance of Hurricane Irma, local government officials made public announcements directing residents with disabilities to shelters. Despite these good faith efforts, there was a communication breakdown and many residents with disabilities found themselves at shelters that did not offer the appropriate services.

Similar to the program in Miami-Dade, North Carolina Emergency Management (“NCEM”) is authorized by law to create a model voluntary registry for use by political subdivisions to identify “functionally and medically fragile persons in need of assistance during an emergency.” Local governments are authorized to coordinate “voluntary registration of functionally and medically fragile persons in need of assistance during an emergency either through a registry established by this subdivision or by the State.” Some local governments, like New Hanover County and the City of Fayetteville have implemented these types of voluntary registries. Information submitted to the registries must be kept confidential and is not considered a public record.

Another approach is to collaborate with agencies already engaged with relief work at the local level. One example is that of the American Red Cross. Local chapters coordinate closely with first responders who often have detailed information on the needs of communities and are well-positioned to gather additional information. In September of 2010, the National Disability Rights Network (“NDRN”) signed a memorandum of understanding (“MOU”) with the American Red Cross to “provide a framework for cooperation between the two organizations in rendering services to communities and assistance before, during, or after disaster events in the United States.” Together they can mobilize community resources to those in need.

One of the first federal agencies that people think of when there has been a natural disaster is the Federal Emergency Management Agency (“FEMA”), created by Executive Order in 1979. President Carter delegated authority to the Director of FEMA to “establish Federal policies for, and coordinate, all civil defense and civil emergency planning, management, mitigation, and assistance functions of Executive Agencies.” FEMA is tasked with “providing an orderly and continuing means of assistance by the Federal government to State and local governments in carrying out their responsibilities to alleviate the suffering and damage which results from disasters” that “cause loss of life, human suffering, loss of income, and property loss and damage.”

FEMA, administered within the Department of Homeland Security, implements the legislative mandates of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. The Stafford Act, as it is called, lays out the statutory national response framework, providing most of the legal framework for activities undertaken by FEMA and FEMA programs. Importantly, the Stafford Act requires that each state has a plan with procedures in place for emergencies.

In order to support local governments, FEMA established the Office of Disability Integration and Coordination in 2010. Each FEMA regional office is staffed with a Regional Disability Integration Specialist who provides technical assistance and works with each state in the region to ensure disaster planning is inclusive of people with disabilities. The specialist connects local governments with information, technical resources, and training programs throughout the year.

North Carolina’s emergency planning and response activities are mandated by state law with a “bottom-up” information structure.

In North Carolina, the main responsibility for emergency management rests at the county level. Municipalities and counties may establish their own emergency management agencies, but are not required by law to do so. For example, the City of Fayetteville has taken the lead on emergency planning within the municipal jurisdiction and coordinates with Cumberland County. Counties and municipalities may also form joint emergency management agencies. The bottom line, however, is that “all emergency management efforts within the county will be coordinated by the county, including activities of the municipalities within the county.” Only counties that comply with planning and preparation requirements generated by the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (“NCDPS”) will be eligible for state and federal funding.

The North Carolina Emergency Management Act, enacted in 1977, sets forth the authorities and responsibilities of state officials, agencies, and local governments in “prevention of, preparation for, response to, and recovery from natural or man-made emergencies.” During an emergency, the Governor may direct and compel evacuations from an emergency area, impose prohibitions and restrictions in an emergency area, direct state and local agencies and officers to assure coordination, make state funds available for emergency assistance, and declare a disaster.

The Director of the NCDPS oversees the State Emergency Response Team, which is made up of representatives from the departments of Public Safety, Transportation, Health and Human Services, Environmental Quality, Agriculture and Consumer Services, and “any other agency identified in the North Carolina Emergency Operations Plan.” During a major emergency, these representatives help to coordinate relief efforts and provide support to local and county governments by bringing in emergency resources and expertise that the local governments do not have.

NCEM, within the NCDPS, prepares and maintains the state plans for emergencies, including the North Carolina Emergency Operations Plan (NCEOP). The NCEOP is a state-level plan based on information provided by local governments. In an emergency, federal agencies support state agencies in accordance with the NCEOP and state agencies support local governments in meeting the needs they identified in their local plans. Additionally, the NCEM oversees coordination and maintenance of liaison with other states, the federal government, and public and private agencies as well as manages intrastate and interstate mutual aid planning implementation and resource procurement to support the emergency response activities.

Outside the scope of NCEM and NCEOP are individual facilities that provide medical treatment and services to people with disabilities. They are regulated by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). In North Carolina, the state DHHS Division of Health Service Regulation provides oversight of these facilities. The statutory requirements of emergency plans are category-specific and incorporated into the facility licensing requirements. A facility must be compliant with the state requirements for emergency planning or risk loss of license.

An example of this has been illustrated by the post-Irma tragedy that occurred at the Rehabilitation Center at Hollywood Hills in Florida where 11 nursing home residents died after their facility lost power to the main air conditioning compressor. The state has now revoked the license of a different nursing home owned by the same owner for failure to comply with licensing requirements.

Plans to rebuild and reintegrate residents with disabilities must be undertaken.

Current conditions for individuals with disabilities in Puerto Rico are dire as compared to those in post-hurricane Florida. The communities in Puerto Rico do not appear to have emergency plans and procedures that incorporate the needs of residents with disabilities that live independently. Since Hurricane Maria, residents of Puerto Rico with disabilities have been largely cut off from the medical and social services on which they depend for health and independence. As a result, many fear lives have been and will continue to be lost.

During emergencies, large-scale mobilization occurs to keep patients in hospitals and health facilities alive when there is widespread loss of power, water, access to medications, or damage to building infrastructure. Only up until recently, Puerto Rico’s power grid had been down since Hurricane Maria hit the island. This placed patients and medical providers in a precarious position. In situations like this one, Disaster Medical Assistance Teams can move in quickly to help hospital patients and facility residents in the impacted area; however, these are not intended to serve communities in the long-term. Plans to rebuild and reintegrate residents with disabilities must be undertaken.

When Mrs. Green attended a meeting in Robeson County in August 2017, there were still approximately 30 people the county was trying to move into accessible housing. The crisis continues for many. Immediately after Matthew, 2,987 residents applied for funds to rebuild damaged homes, to elevate homes to prevent future flood damage, or to simply sell their property and move. In September 2017, NCEM had funds for only approximately 800 of those people. The storm damage to date tops more than $2.8 billion to property and another $2 billion in lost business. Officials are calling for better flood mitigation planning.

They must also incorporate lessons learned from this devastating event to improve the inclusiveness of the emergency planning and preparation to better meet the needs of the medically fragile and those with disabilities. Official hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30. Two things are certain: June 1, 2018 will arrive on schedule and there will be another hurricane in North Carolina.