NFL Cheerleaders getting rowdy over low wages

Cheerleaders for the Oakland Raiders and Cincinnati Bengals filed suit for wage theft and unfair employment practices.

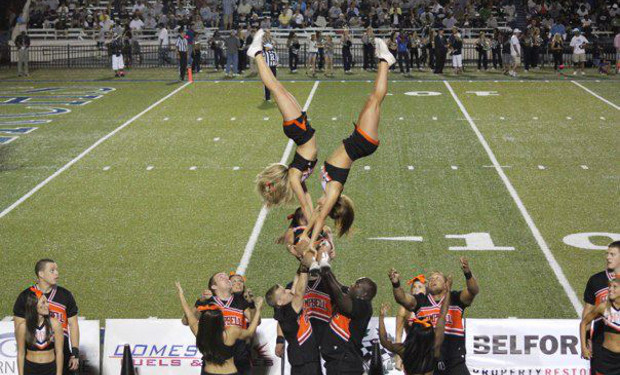

In America, football and cheerleading go hand in hand. From a young age, boys across the nation dream of making it big in the National Football League (NFL) and often those young girls who cheered them on from the sidelines also dream of performing at a professional football game. With the same big dreams of being a part of one of the most lucrative sports leagues in the country, it would only seem logical that both of these aspiring athletes would be fairly compensated for their hard work. In 2012, the Oakland Raiders were valued at $825 million, with revenue of $229 million and the lowest paid player making $405,000. Despite these high figures, the Oakland Raiders’ cheerleading squad, The Raiderettes, is only paid $1,250 per season per cheerleader—as long as the cheerleaders do not receive any fines and are not benched for rules violations set out in their at-will employment contract.

The team fines Raiderettes ten dollars or more for offenses like failing to bring the right pom-poms or a yoga mat to practice. Additionally, a cheerleader who gains five pounds or who appears “too soft” to the squad’s director is benched for the next home game, has to stay in the locker room, and forfeits the $125 wage she would have made for participating in the game, even though she still must take part in pregame and halftime activities.

“I have never seen an employment contract with so many illegal provisions.”

In January 2014, Lacy T. 1 accused the Raiders of failing to pay the Raiderettes minimum wages for their work, both on and off the field. Additionally, according to the complaint, the Raiders withheld the cheerleaders’ pay until the end of the season, in violation of state law. The suit also accused the Raiders of violating California law by requiring the Raiderettes to pay all costs of travel, team-mandated cosmetics and other items; by fining them for such offenses as bringing the wrong pom-poms to practice; and by prohibiting them, in their work contracts, from discussing their pay with each other. Moreover, the cheerleaders must buy accessories such as tights, false eyelashes and a yoga mat, and pay for a team-selected hairstylist, whose appointments cost several hundred dollars. Lacy T. claims in her suit to have spent about $650 on the required hairstylist appointments alone this past season. As Lacy’s attorney stated, “I have never seen an employment contract with so many illegal provisions.” The suit was filed in Alameda County Superior Court as a proposed class action on behalf of forty current Raiderettes and other members of the squad over the past four years.

The Raiderettes are not the only squad pursuing a class action suit. A cheerleader for the Cincinnati Bengals, Alexa Brenneman, has sued (pdf) the football franchise, accusing the team of violating federal wage laws. The complaint alleges that Brenneman was paid $2.85 an hour, five dollars less than the Ohio minimum wage in 2013. The complaint seeks a judge’s order to stop the Bengals from violating the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Ohio Minimum Fair Wage Standards Act, as well as unpaid wages for cheerleaders, attorney fees and court costs. U.S. District Judge Michael Barrett, who is assigned to hear the case, will first have to determine whether the lawsuit meets certain criteria to proceed as a class action or collective action under federal labor law. According to an attorney on the legal team representing Brenneman, if the suit is certified, all Ben-Gals since the 2011 season can join. Up to fifty cheerleaders could be eligible.

According to the Baltimore Ravens’ 2009 cheer squad handbook, professional cheerleading is depicted as a “ponzi scheme in hot pants.”

The usual game day routine for Alexa Brenneman, Ben-Gal cheerleader for the Cincinnati Bengals, involved waking up at 4 a.m. to get ready for a ten-hour day at the stadium. Her hair and makeup had to be done in the manner that her employment contract required before she reached the stadium each morning. Once at the stadium, the squad had two practices and an autograph signing before the game. After kick-off, the next four hours were spent cheering and dancing with no meal break. The demands placed in contracts seem to be similar throughout the NFL cheerleading squads. According to the Baltimore Ravens’ 2009 cheer squad handbook, professional cheerleading is depicted as a “ponzi scheme in hot pants.”

It is also a common misconception that these cheerleaders can earn a profit from the infamous calendars in which they annually pose. As the complaint states, the Ben-Gals are required to pose for and promote the Cincinnati Ben-Gals calendar without pay while the team makes money from calendar sales. One member of the Baltimore Ravens squad shared that once the calendars are printed, all cheerleaders are required to purchase a certain number of issues, one hundred for female and twenty for male cheerleaders. After buying each issue for twelve dollars, the cheerleaders can then sell them for fifteen dollars apiece, turning up to at most a $300 profit.

For the cheerleaders, the real money comes from appearances, but even that is negligible. If the appearance is for charity, the team will charge $175 per cheerleader per hour; otherwise, the fee is $300 per hour. Of that fee, each cheerleader takes home around fifty dollars an hour. However, in an average season, a cheerleader will make only thirty or so appearances, and many of those are unpaid. For charity events set up in the NFL’s or the team’s own name, cheerleaders are expected to attend without compensation, and rules require them to attend charity events at least twice monthly, depending on availability.

Having a cheerleading squad is evidence of a successful franchise.

The NFL is the most lucrative sport in America and brings in about $9 billion in revenue annually. There are many aspects of football that keep fans captivated for the entire season and entice them to spend money on tickets, memorabilia, and other team merchandise. Having a cheerleading squad is evidence of a successful franchise; the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, for example, are arguably more famous than the actual football team and bring in an estimated $1 million per season for the franchise.

According to the plaintiffs’ estimations, NFL cheerleaders’ wages are essentially equivalent to those of unskilled, minimum wage workers. Cheerleading may not yet be considered a “sport” at the collegiate level despite the required level of commitment, but at the professional level it requires significant training that is intensely competitive and physically demanding. It can also lead to a number of injuries, no matter the level of competition.

“I didn’t feel comfortable complaining about my pay. They would probably just kick me off the team.”

The illegal pay policies are written into the Raiderettes’ contracts as well as the contracts of other squads within the NFL. Many ask why these women enter into these illegal contracts, but according to one Raiderette, becoming a professional cheerleader is many girls’ lifelong dream. Being in a well-respected and prestigious squad is very important, explaining why these cheerleaders are reluctant to join the class action suit. Lacy T. recently answered this question in an interview with Josh Eidelson of Salon.com:

It was also a dream of mine to dance in the NBA and the NFL…The Raiderettes were voted the No. 1 NFL cheerleading team two years in a row. So they’re a very prestigious group of women, and they’re known for their class and their talent. And so to want to be a Raiderette, I think, is a lot of girls’ dream…and once you’re a Raiderette, you know how special it is to be one—so I think that’s also a reason why a lot of girls are scared to come forward.

These women are essentially told that they are “lucky” to get the chance to be NFL cheerleaders. Lacy T. and other cheerleaders report that they are told that there are hundreds of women who could replace them. “I didn’t feel comfortable complaining about my pay. They would probably just kick me off the team,” says Lacy T.

According to attorneys for the Raiders cheerleaders, this is an NFL-wide practice. When asked what the penalties for the NFL teams could be, one attorney stated that the women would be “entitled to any back wages they’re owed, and they will be entitled to penalties. It could be as much as $10,000 to $20,000 per Raiderette, and there are 40 in any given year, and we go back four years.”