Open Wide, Your Identity is in Question

The Supreme Court’s controversial Fourth Amendment decision in Maryland v. King determined that a State’s interests in investigating crimes outweigh the privacy interests of those suspected of crimes.

People detained “for minor offenses can turn out to be the most devious and dangerous criminals. Hours after the Oklahoma City bombing, Timothy McVeigh was stopped by a state trooper who noticed he was driving without a license plate. Police stopped serial killer Joel Rifkin for the same reason. One of the terrorists involved in the September 11 attacks was stopped and ticketed for speeding just two days before hijacking Flight 93,” wrote Justice Kennedy, quoting Florence v. Bd. Of Chosen Freeholders of Cnty. of Burlington (pdf), in the majority opinion of the Supreme Court’s latest Fourth Amendment case, Maryland v. King (pdf).

Justice Kennedy points out the potential frequency at which high-alert criminals can show up right under the nose of law enforcement, as well as the need for superior identifying mechanisms to ensure that these individuals do not slide through the cracks. From the majority’s viewpoint, identifying an arrestee should mean much more than asking for his given name and date of birth. To fully accomplish what it is that law enforcement sets out to do—to protect the public from those who put our life and liberty at risk—they must ascertain a suspect’s entire identity, including, and perhaps most importantly, the individual’s full criminal history.

The most common means of identifying a suspect, and therein his criminal past, is through the traditional process of taking fingerprints and mugshots. Currently, all states allow law enforcement to scan arrestee’s fingerprints through an electronic database to find any matches for prior crimes. Fingerprinting is an accepted means of identification, just one of the steps in the routine booking process of criminal suspects. And although a fingerprint is distinctive to a single individual, it can hardly be argued that an arrestee’s privacy interests have been trampled upon based on a mere ink stamp of the arrestee’s fingers at the police station.

But is there a difference between pressing a fingertip to an inkpad and a quick swab on the inside of a cheek?

But is there a difference between pressing a fingertip to an inkpad and a quick swab on the inside of a cheek? Both procedures are quick and painless. Neither requires surgical intrusion into the arrestee’s body. Neither poses any threat to the health or safety of the individual. “In this respect, the only difference between DNA analysis and the accepted use of fingerprint databases is the unparalleled accuracy that DNA provides,” Justice Kennedy pointed out.

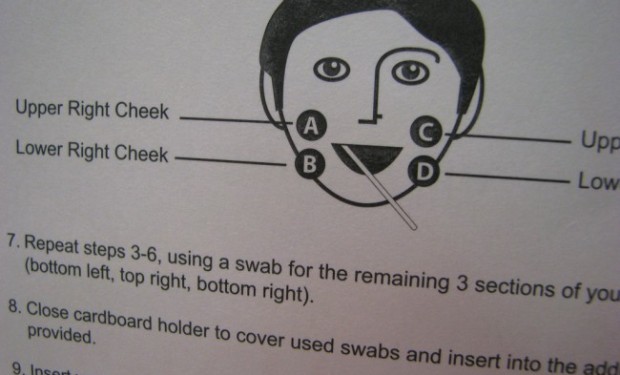

The question of whether DNA swabbing could truly be held to the same level of intrusion as fingerprinting was heard by the Supreme Court in the October 2012 term. Buccal swabbing, or the collection of DNA cells from the inside of a cheek, of individuals convicted of felonies is currently allowed in all states. However, at the time the case reached the Court, a little over half of the states and the federal government had laws permitting law enforcement to gather DNA from those who had been arrested, but not yet convicted, of a crime. Maryland was one such state.

In the King case, Alonzo King Jr., a Maryland resident, was taken in for charges of first and second degree assault in 2009. A buccal swab was conducted pursuant to Maryland’s law, which allowed for DNA collection from arrestees of violent crimes. King’s DNA was submitted into the statewide database and linked him to the DNA of an unsolved rape case from 2003, for which he was subsequently tried and convicted.

King appealed, arguing that the DNA collection is the type of search that is unreasonable per se because it is both warrantless and suspicionless. Maryland’s highest court, the Court of Appeals of Maryland, found for King (pdf). The Court noted that when gauging the privacy interests of individuals, King’s status as an arrestee gave him privacy expectations more akin to that of an innocent individual rather than the greatly diminished expectations of a convicted criminal. The Court of Appeals dismissed the notion that DNA collection was essentially the same as a fingerprint, stating that a fingerprint could only provide information about a person’s identity.

“We cannot turn a blind eye to the vast genetic treasure map that remains in the DNA sample retained by the State.”

DNA samples, however, could provide much more in-depth and private information about an individual. While the Court acknowledged that the Maryland law limited the use of the collected DNA to solely identifying information, it stated that “we cannot turn a blind eye to the vast genetic treasure map that remains in the DNA sample retained by the State.” The conviction was thrown out by the Court of Appeals of Maryland on the grounds that police had neither a warrant nor individualized suspicion for the search. According to the Court, King’s privacy interests exceeded any interests Maryland might have in identification purposes.

When the Supreme Court of the United States decision was handed down in June 2013, Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion dismissed King’s argument regarding the warrant, noting that because the suspect was already in custody for a serious offense supported by probable cause, the need for a search warrant was significantly lessened. The focus would in turn rest on the reasonableness aspect, since a search incident to a valid arrest is legitimate without assessment of individualized suspicion. The Supreme Court’s analysis of the reasonableness of the search would be gauged by the same long-standing test as was used by the Court of Appeals—balancing the governmental interest to be furthered against the severity of the intrusion of the individual’s privacy.

The state’s interests ascertained by the Supreme Court during its analysis, however, would prove to be much more significant than those found by the Court of Appeals. The interests were so great that during oral argument for the case (pdf), Justice Samuel Alito noted that the case was “perhaps the most important criminal procedure case this court has heard in decades… So this is what is at stake: lots of murders, lots of rapes that can be solved using this new technology that involves very little intrusion on personal privacy.” Alito would later join Justice Kennedy in his majority opinion upholding the conviction, stating that DNA plays a critical role in furthering the governmental interests of detaining suspected criminals.

After discussing what the majority found to be tremendous governmental interests that would be furthered by the use of DNA sampling, the majority opinion went on to forecast and respond to arguments from critics. Justice Kennedy noted that it was undisputed that the sole purpose for law enforcement officers using DNA would be to ascertain a unique identification profile that could be matched to future samples. He acknowledged concerns that DNA could be used for more than that purpose. But Justice Kennedy also stated that because the DNA samples were only to be tested for the permitted reason, the practice was similar to the already existing safeguard established in school drug-testing cases.

In such cases, the Court accepted the use of drug testing in schools but only to the extent that an individual’s urine would be checked for illegal drugs—not any of the other numerous biological dispositions that could be realized from a urine sample, such as pregnancy, epilepsy, or diabetes. “If in the future police analyze samples to determine, for instance, an arrestee’s predisposition for a disease or other hereditary factors not relevant to identify, that case would present additional privacy concerns not present here.”

Justice Scalia’s dissent discusses the irony of the outcome, stating that the only group of people who will be affected by the ruling are those arrestees who would have eventually been acquitted of the charges against them.

But this nod to the future was not enough to calm the furor of Justice Scalia, who gave a rare oral dissent from the bench. Justice Scalia, a staunch conservative, sided with three typically liberal leaning justices in the dissent, further demonstrating the significance of the King case. The dissent discusses the irony of the outcome, stating that the only group of people who will be affected by the ruling are those arrestees who would have eventually been acquitted of the charges against them. These people, had the law not been upheld, would not be subject to DNA collection, due to their status as a mere arrestee, not yet convicted. “In other words,” Scalia admonishes, “this Act manages to burden uniquely the sole group for whom the Fourth Amendment’s protections ought to be most jealously guarded: those that are innocent of the State’s accusations.”

The ACLU sided with the dissent, calling the holding “a serious blow to genetic privacy.” While primarily echoing a key point in Scalia’s dissent—that subscribing to the belief that law enforcement’s motive in using DNA is simply to identify an arrestee and not for an investigative motive “taxes the credulity of the credulous”—the ACLU had stated in its amicus brief submitted to the Court that the implications of such a holding would reach well beyond the confines of Maryland.

“Restrict the government’s authority to engage in suspicionless, warrantless collection of DNA to those who have crossed our criminal-justice systems’ most fundamental line: conviction.”

The amicus brief (pdf) points out that while the King case centered around a Maryland state law, many states have similar, but broader, laws regarding DNA sampling. One such example can be found in California, which allows DNA sampling for individuals arrested for any felony, even including crimes like illegally subleasing a car or simple drug possession. California’s laws, similar to those of the federal government, allow an arrestee’s DNA information to be analyzed and uploaded into the database even before they are charged with a crime. The ACLU’s brief concluded this point by urging the Court to “restrict the government’s authority to engage in suspicionless, warrantless collection of DNA to those who have crossed our criminal-justice systems’ most fundamental line: conviction.”

While the ACLU warned of expansion and repercussion in a negative sense, many officials such as Marcus Brown, superintendent of the Maryland state police, believe the ruling will encourage other states to enact laws similar to Maryland’s. Brown is excited for the prospects of DNA sampling and how helpful it will be in the booking process, calling it “the modern-day fingerprint.”

It is clear that the Court’s decision was a momentous one, and with a 5-4 split of the Justices, albeit not along usual ideological lines, the controversial decision is open for criticism. As with many technological advances, the ultimate legal balancing act ensues: weighing the tremendous ability to combat and solve crime against the long standing, steadfastly guarded rights guaranteed by our forefathers in the Fourth Amendment.