Redlining In North Carolina: A Pervasive Legacy

It is no secret that North Carolina has a rather dismal history of upholding racial segregation. In the Jim Crow era, cities like Winston Salem and Asheville embraced racist policies designed to enforce segregation, particularly in the area of housing. The legacy of these practices has led to devastating consequences that can clearly be seen today. As national lawmakers and local leaders attempt to find a way to remedy the wrongs of the past, a clear-cut path has yet to emerge.

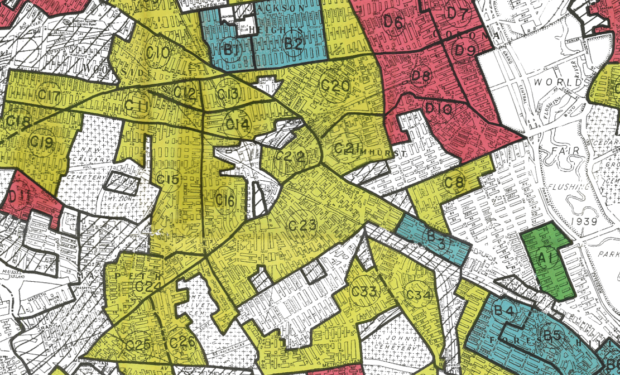

A Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of Richmond, Virginia, guided lenders as to where and where not to invest. Black neighborhoods were often denoted “Hazardous” and marked in red, giving rise to the term “redlining.” | Source: Mapping Inequality

A Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of Richmond, Virginia, guided lenders as to where and where not to invest. Black neighborhoods were often denoted “Hazardous” and marked in red, giving rise to the term “redlining.” | Source: Mapping Inequality

It is no secret that North Carolina has a rather dismal history of upholding racial segregation. In the Jim Crow era, cities like Winston Salem and Asheville embraced racist policies designed to enforce segregation, particularly in housing. The legacy of these practices has led to devastating consequences that can clearly be seen today. As national lawmakers and local leaders attempt to find a way to remedy the wrongs of the past, a clear-cut path has yet to emerge.

A History of Redlining

One of the most effective methods of maintaining segregation was implemented by the federal government in the 1930s through creating the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The FHA was designed to insure mortgages issued by approved lenders, which stabilized the housing market and theoretically increased opportunities for home buyers.

To determine whether a neighborhood was eligible to be insured for mortgages, the FHA used rating systems based on factors like income, race, occupation, and immigration status to divide neighborhoods into color-coded zones. If the area were deemed a “red zone” by the rating system, it would not be eligible for new loans, allowing lenders to either refuse to extend credit altogether or offer costly rates. Predictably, African American neighborhoods were almost automatically “redlined” by the FHA, effectively cutting off any chance that investors would risk lending to occupants.

The Rise of Restrictive Covenants

Restrictive covenants limiting home sales only to white homeowners soon arose to preserve the security and homogeneity of neighborhoods deemed desirable by the FHA. Long after explicitly segregationist ordinances were deemed illegal in North Carolina, restrictive covenants provided an ingenious solution, because as private actions, they were not open to attack as public policies.

Although the Supreme Court held that racial covenants were unenforceable in the landmark case of Shelley v. Kraemer, zoning ordinances quickly filled the gap left behind. The effects of these ordinances are very much present today, with areas that were traditionally categorized as preferable under the FHA’s rating system zoned for single-family residences. In contrast, predominantly African American neighborhoods have historically been zoned for industrial usage or multi-family residences, thus keeping property values artificially low.

Despite the abolition of racial covenants, the deeds of many homes in neighborhoods across Charlotte, including the exclusive neighborhood of Myers Park, still contain racist language preserved from this era, dictating that “this lot shall be owned and occupied by people of the Caucasian race only.” This terminology created a public furor in 2010 when the Myers Park Homeowners’ Association posted an old deed as a reminder of neighborhood restrictions while seemingly oblivious to the racial provision contained in the deed. Charlotte’s community relations manager deemed the neighborhood’s actions a violation of the Fair Housing Act and required Myers Park to settle or face court action. The outrage over the deed reveals that most of the public believes such racial covenants are a relic of the past when the past is much closer than most would care to acknowledge.

Modern Legacy of Redlining In North Carolina

Today, areas targeted for redlining by the FHA have become economic gold mines for developers looking for new areas for investment. In cities like Durham and Asheville, gentrification and new construction directly overlap with previously redlined neighborhoods, creating a bizarre reversal where formerly undesirable locations are now premium real estate thanks to their artificially depressed property values.

Rising property values also mean rising property taxes and rent, and many long-term residents who find themselves surrounded by new construction feel the pressure to cash out. Once again, African Americans and other members of traditionally disenfranchised populations are being pushed to the fringes through means that have been deemed entirely legal.

A recent study conducted by the North Carolina Poverty Research Fund (NCPRF) found that historically redlined areas are still among the most chronically distressed in Durham today and have been so continuously since the 1970s. The report also found that “median home values and homeownership rates are about half the rates for the city and county.”

The lower numbers for homeownership directly impact the wealth disparity between African American and white citizens. In Charlotte, homeowners in largely minority neighborhoods have accumulated far less wealth in the form of home equity, with the median home value hovering at around $72,000 for tracts where 97% of the population are people of color, compared to $870,500 for neighborhoods that are 93% white.

Redlining’s impact can be seen in even the smallest of details, such as the number of trees planted in redlined neighborhoods versus other residential areas, contributing to lower home values. The study conducted by the NCPRF found that in predominantly African American neighborhoods in Durham, tree coverage is still only at about 10%, compared with white neighborhoods where tree coverage hovers around 60%. This might seem trivial, but the lack of tree cover actually leads to noticeably hotter temperatures in historically redlined neighborhoods, according to another 2020 study. While the policies that created this disparity are no longer legal, tangible consequences clearly remain.

Finding A Way Forward

For those willing to acknowledge the pervasive harm caused by redlining, finding a way forward remains a daunting task. Proposed legislative remedies vary widely and are hotly debated by proponents and detractors. On the campaign trail, Vice President Kamala Harris proposed a $100 billion plan to counteract the effects of redlining by offering the assistance of up to $25,000 for down payments to those who reside in historically redlined neighborhoods. Homebuyers could then use these grants to purchase homes anywhere.

Critics of her plan cite concerns that such a costly solution borders on objectionable reparations. Another hurdle that must be overcome is the reality that many of the residents in formerly redlined tracts are no longer predominantly African American, so offering aid to those still living in these areas might not actually have that significant of an impact on the African American community. Finally, the $100 billion price tag is likely to be difficult to swallow for Americans in the middle of a devastating pandemic and the worst period of economic upheaval in recent memory.

Another way the federal government could improve the situation it helped to create would be to implement an Economic Fair Housing Act that would fill the gaps left by the Fair Housing Act. Although the latter prevents discrimination based on explicit racial zoning, there is no such provision for exclusionary zoning policies. Over time, these zoning ordinances have become a substitute for the now illegal racial provisions and have contributed significantly to ongoing disparities between white and black residential opportunities.

A different, perhaps less politically challenging, way to address housing disparities would be to actually enforce the FHA’s statutory duty to promote equitable housing. The Obama administration attempted to implement a rule to activate the FHA’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing requirement in 2015. This rule required the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to take meaningful action to address areas of historical segregation and overcome barriers that perpetuated discrimination. As envisioned, it would have allowed HUD to enforce the FHA rigorously, but its long-term effects have yet to be seen, as the Trump administration suspended enforcement in 2018. Re-implementing this rule would allow the FHA to have some teeth and change course from the relatively weak enforcement efforts of the past.

Some North Carolina city planners are considering expanding housing mobility programs and ending single zoning housing restrictions at a more local level. In particular, Charlotte and Raleigh are exploring changes that could allow multi-family housing in traditionally single-family zones.

There is likely no perfect solution to such an entrenched problem. Regardless of the ultimate form of the solution, any positive change will require significant investment in the community rather than mere gentrification. If the effects of redlining are ever to be assuaged, it is critical that those seeking a solution be willing to learn from a history of failure and face the consequences of discrimination head-on.