The current trend in politics is a move away from the center and towards the wings of both major parties. This growing partisanship is seen at all levels of government and has placed an even greater emphasis on the redistricting process. Redistricting is now a way for the party in power to consolidate their electoral majority until the next census and is often met by lawsuits from those aligned with the minority party. Partisan redistricting paired with North Carolina’s checkered past in regards to voting rights for minorities made the General Assembly’s 2011 redistricting even more hostile than usual.

The Plaintiffs timely appealed the trial court’s decision, and briefs for each side were filed in late 2013.

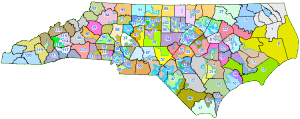

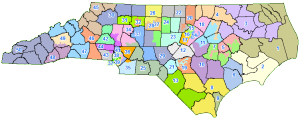

Following each census conducted by the United States Government, the General Assembly of North Carolina is entrusted with redrawing the voting districts to match the changes in population seen over the last decade. In the Summer of 2011, the General Assembly enacted new voting districts for both the House of Representatives and the Senate and for the United States House of Representatives. In response, a number of interest groups filed suit against the State over the redistricting plans for thirty voting districts.

Plaintiffs argue that the Defendants—state legislators—unconstitutionally packed the districts with minorities to weaken their voting power. Defendants believe that creating the majority minority districts follows the Voting Rights Act, even though data shows that minorities have been able to elect their preferred representatives in less than majority districts—despite this being the reason for majority minority districts. These suits were consolidated, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of North Carolina appointed a three-judge panel to hear the case. After hearing motions from both sides, a bench trial was held in June of 2013, and in July, the panel ruled unanimously in favor of the Defendants, upholding their redistricting plans. The Plaintiffs timely appealed the trial court’s decision, and briefs for each side were filed in late 2013.

Filings of interest with the Supreme Court of North Carolina may be found as follows:

The Record on Appeal

Plaintiffs-Appellants’ brief

Defendants-Appellees’ brief

Plaintiffs-Appellants’ Reply briefAll appellate filings in the redistricting cases can be found at the Court’s Electronic Filing Site.

Even though the trial court ruled in favor of the General Assembly, the Court found that twenty-six of the thirty at-issue districts were drawn with race as their primary factor. After finding that race was the main reason for drawing those districts, the Court applied strict scrutiny, which requires the legislator-defendants to provide a compelling interest for the race classification and for the classification to be narrowly tailored to that interest. The Defendants offered two reasons for using the racial classification: first, to avoid liability under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), and second, to ensure preclearance of the redistricting plan under Section 5 of the VRA.

The three-judge panel found that Plaintiffs did not carry their burden in proving the Defendants’ reasons did not withstand strict scrutiny. The panel thought it should defer to the Legislative branch’s “reasonable fears of, and their reasonable efforts to avoid, Section 2 liability,” as well as the Legislature’s interpretations of Section 5 of the VRA. (see pages 1281 and 1285 of the Record on Appeal).

Both sides’ arguments, at trial and on appeal, revolve around Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Both sides’ arguments, at trial and on appeal, revolve around the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the state and federal Constitutions. The Voting Rights Act was enacted to protect the rights of minority voters throughout the country, particularly in the South. Southern states had notoriously limited the rights of minority voters since minorities were given the right to vote. Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act are the main sections implicated in the creation of the at-issue voting districts.

Section 2 prohibits any jurisdiction in the country from instituting voting laws that discriminate against individuals because of their race, color, or inclusion in a language minority group. The Supreme Court held in Mobile v. Bolden that Section 2 restated the protections afforded by the Fifteenth Amendment. Congress in 1982, however, expanded Section 2’s protections by lowering the standard of proof for plaintiffs to be successful. The amended Section 2 required only that there be a discriminatory effect behind the law, not a discriminatory purpose.

Section 5 requires certain jurisdictions, almost exclusively in the South, to pre-clear any changes to voting laws, no matter how small. This was a novel approach that effectively stopped jurisdictions from continuously changing their discriminatory voting policies to limit minority voting. Unlike Section 2, which lasts indefinitely, Section 5 had a definite life span when it was enacted. Initially, Section 5 was to last for only five years, but Congress reauthorized it on several occasions. Its last reauthorization in 2006 will continue until 2031.

Defendants’ response is that following the 2010 census, the population of North Carolina had changed, as people moved into and out of the state and throughout the counties.

The Supreme Court of the United States heard the case of Shelby County v. Holder (pdf) in the summer of 2013, and ruled that Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act—which is used to determine which states are subject to preclearance under Section 5—was unconstitutional. The Court reasoned that relying on data and formulas created when the VRA was originally passed to force only some states to comply with it today was unconstitutional.

Enormous strides had been taken by the jurisdictions held accountable under Section 5 of the VRA, and these jurisdictions often had higher turnouts for minorities than jurisdictions where Section 5 preclearance was not required. Using old formulas to force only some jurisdictions to pre-clear new voting laws, but not others, went against the federalist principles espoused in the United States Constitution. While not directly striking down Section 5 of the VRA, eliminating the method for determining which states should be subject to preclearance effectively served to negate Section 5.

The Plaintiffs on appeal argue that the steps taken by the General Assembly are beyond what is required by Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Plaintiffs regard Section 2 as not requiring racial proportionality; this racial proportionality, Plaintiffs believe, is really racial balancing by the General Assembly. There are a number of recent Supreme Court cases, including Parents Involved in Cmty. Sch. v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, holding that racial balancing is unconstitutional and that the Constitution requires the Government to treat its citizens as individuals and not as members of any class. Plaintiffs state that because the Supreme Court has found racial balancing unconstitutional in other contexts, it should do the same for the redistricting of voting districts.

Plaintiffs also argue that because the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act was unconstitutionally applied to North Carolina in Shelby County, the General Assembly’s reliance on Section 5 in 2011 to create the new districts was not compelling. Defendants’ response to this is that following the 2010 census, the population of North Carolina had changed, as people moved into and out of the state and throughout the counties. The General Assembly is required by the State Constitution to comply with one person, one vote requirements, which means that the General Assembly had to redistrict the state’s voting districts to reflect the changes in population.

Not only was the General Assembly required to comply with the State Constitution, it also had to comply with the then-applicable Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. To comply with Section 5, the General Assembly had to create voting districts that it believed would be pre-cleared by the Department Of Justice—districts that were indeed pre-cleared by DOJ. Defendants have urged the Supreme Court of North Carolina to side with the trial court’s holding that complying with Section 5 was a compelling state interest because the voting districts would not have been in compliance with the Voting Rights Act unless they could be pre-cleared under Section 5.

The outcome of the case could impact voting in North Carolina for decades to come, as well as other voting laws recently enacted by the General Assembly that allegedly unfairly restricts the rights of minority voters.

The two sides in this case are not the only groups with a vested interest in the outcome. Nine law professors who focus on election law wrote a brief as amici curiae to protest the trial court’s ruling (pdf) and to persuade the Supreme Court of North Carolina to side with their interpretation of the Voting Rights Act. The amici law professors believe that the General Assembly’s use of race to create voting districts was not required by the Voting Rights Act. Though amici agree with the trial court that strict scrutiny should apply, they believe the court was too deferential to the General Assembly. In finding that the General Assembly had a compelling interest in avoiding Section 2 liability under the Voting Rights Act, amici believe the trial court did not go far enough in determining whether a Section 2 lawsuit would have any likelihood of success. Notably, there has not been a successful Section 2 lawsuit in North Carolina in over three decades.

On January 6, 2014, the Supreme Court of North Carolina will hear oral arguments from both sides over the at-issue voting districts. Importantly, in the short-term, the oral arguments could prove insight into how the Justices on the Court feel about the changes in the state’s voting districts. The Court’s decision, whether it affirms or reverses the trial court’s decision, likely will be appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States. In the long-term, the outcome of the case could impact voting in North Carolina for decades to come, as well as other voting laws recently enacted by the General Assembly that allegedly unfairly restrict the rights of minority voters.

[Editor’s note: This article will be updated when the Supreme Court of North Carolina publishes its opinion in the redistricting cases.]