Taunted by the Haunted: The Extreme Horror Attraction that Continues to Evade Legal Liability

Reaching the Tennessee State Senate: 200,000 Signatures Required.

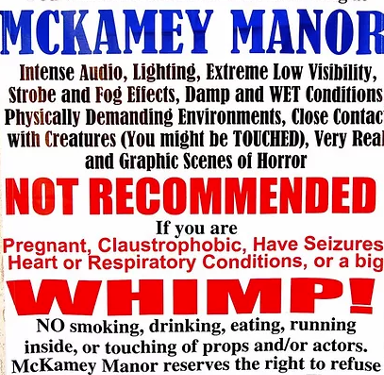

Approximately 170 thousand signatures have been gathered on Change.org in an attempt to have an extreme scare attraction in Tennessee shut down. McKamey Manor is an experience offered in Summertown, Tennessee and Huntsville, Alabama that boasts it is “not your standard . . . haunted house.” The creator of the petition to shut down the house, Frankie Towery, describes the Manor as “a torture chamber under disguise,” and claims that participants have suffered a range of injuries, from passing out to fractured bones to mental trauma. The petition includes allegations that the owner and employees of the facility waterboard participants, force them to eat unknown things (such as bugs), and wrap duct tape around their heads.

Contract Liability: The 40-page Waiver

Participants are required to read and sign a 40-page waiver prior to being allowed to participate in the experience. While the waiver has not been released to the general public, enough of its contents have been leaked or reported on to give a basic understanding of its provisions. One participant reported that when he signed the waiver, over 100 conditions were listed, including the following: having plastic wrap held tightly over the participant’s face; coming into contact with mouse traps; tooth-pulling; needles; and having the participant’s hands and feet tied via zip-ties.

Are there defenses against such a seemingly outrageous contract?

Upon hearing about the conditions contained in McKamey Manor’s 40-page waiver, a person may be shocked and appalled to learn that such a contract can be enforceable.

For a contract to be considered valid, there must be mutual assent, or agreement, between both parties involved. Here, mutual assent occurs the moment participants sign the Manor’s waiver. Here, McKamey Manor offers a unique, hands-on haunted house experience. In return, participants waive their right to hold the haunted house liable for injuries sustained and agree not to put their hands on actors in response to anything that happens within. The 40-page waiver is intended to ensure that both parties have a reasonably clear concept of what they are getting and giving up.

Most law school students learn about defects in assent in their first year Contracts course. Defective assent is one category of defense against a contract’s enforceability. Both parties of a contract have a right to not be tricked or forced into a contract and a right to have the resulting contract be what was intended by each of them. Two specific examples of defective assent are unconscionability and undue influence.

When a contract “shocks the conscience,” there may be a claim to the defense of unconscionability.

For an unconscionability defense to prevail, there must be an inequality so strong and gross that it is impossible to state it to a person of common sense without producing an exclamation at the inequality. There must be evidence that one of the contracting parties was unable to make a meaningful decision or choice when agreeing to follow through with performance.

McKamey Manor is easily researchable, and the news of their “extreme” horror is easily found. Along with the signing of the 40-page waiver, the owner of McKamey Manor requires a “sports physical” and doctor’s note clearing participants physically and mentally, a background check, a drug test, and proof of medical insurance. Furthermore, participants must be at least 21 or have parental approval if they are between 18 and 20. Thus, the extreme horror experience is intended to attract adults fully capable of making decisions only. Given all the overwhelming information published about the Manor, an individual would have a difficult time proving they were unable to make a meaningful decision before agreeing to contract to participate in the extreme horror attraction.

What about undue influence?

Undue influence occurs when an individual who holds real or apparent authority over another, uses the other individual’s confidence to obtain an unfair advantage. Under a defense of undue influence, a party must prove that the contracting party entered the contract with the intent to target the weak or those easily persuaded or influenced. The aggrieved party must also prove there was a type of special relationship that was ripe to cause such a susceptibility to influence. For example, let us imagine a son and mother who have a close relationship, emphasized because the son has taken care of his mother throughout the latter years of her life. Hypothetically, this relationship may be pointed out if a dispute were to arise as to the son’s impact on a change in his mother’s testamentary will shortly before her death, as his mother could have been more susceptible to his influence.

The aforementioned petition claims that McKamey Manor uses the mental health screening requirement to separate the “weak” from the “strong” and then invites the “weak” to the experience. The allegation in the petition could create enough reasonable cause, though it currently lacks evidence, to sustain a defense of undue influence under the first element if the Manor truly screens for the “weak” as alleged above. The relationship aspect would be harder to prove, though there may be an argument that the $20,000 incentive offered to participants who complete the course creates an influential relationship. As a further note, no one has ever made it all the way through the experience.

How is it possible that such an aggressively hands-on experience could be legal?

The owner, Russ McKamey, explains that while participants are led to believe they are undergoing tortuous treatment, such as waterboarding, it is all just “mind games.” Despite claiming the torture is a “mind game,” McKamey further acknowledges the most serious injury on site was a heart attack from which the participant recovered. The owner furthermore openly admits that participants can leave with bruises, sprains, and cuts, but adds, “you can die at Disneyland, too.”

It seems incredulous that the haunted house may contract in such a way that allows the participants to waive their rights. In a separate analysis here, a case could be made for McKamey Manor having violated the torts of assault, battery, trespass to chattels, and false imprisonment.

However, with any tort claim comes the defense against tortious consequences. One of those defenses is “consent.”

The very nature of the 40-page waiver is to give McKamey Manor consent, thus negating tort liability.

Unfortunately for anyone who actually signs the 40-page waiver, they have handed over their consent along with their signature. Under the defense of consent, an individual cannot claim an intentional tort has harmed them when they have voluntarily consented to the act in question.

For example, when a football player consents to play the sport, they are consenting to tackles and physical contact. However, they are not consenting to being randomly punched in the face for no reason by a player on the opposing team. Here, the participants of McKamey Manor are consenting to the physical contact in the form of over 100 conditions. Unfortunately, given the thoroughness of the waiver, the defense of consent will most likely negate tort liability.

This is what it all boils down to…

McKamey Manor may be a “torture chamber under disguise,” but it is a haunted experience to which people are voluntarily assenting to under contract law and consenting to under tort law. The likelihood their contract will be found unenforceable is low and civil action is unlikely to prevail under an intentional tort. The only potential area of liability McKamey Manor could be responsible for is criminal action; this is a completely different arena than civil action requiring an entirely separate analysis.