BY: KAITLIN ROTHECKER, Guest Contributor

Editor’s Note: The Campbell Law Observer has partnered with Judge Paul C. Ridgeway, Resident Superior Court Judge of the 10th Judicial District, to provide students from his International Business Litigation and Arbitration seminar the opportunity to have their research papers published with the CLO. The following article is one of many guest contributions from Campbell Law students to be published over the next two weeks.

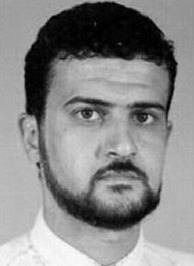

After more than a decade of holding a top spot on the United States’ list of most wanted terrorists, al-Qaeda leader Anas al Libi is awaiting trial in a New York Federal Court. Commonly known by his alias Anas al Libi, Nasih Abdul-Hamed Nabih al-Ruquai’I, faces criminal charges in connection with the 1998 US Embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania. Al-Libi was indicted by the Federal Court for the Southern District of New York in 2000 for his role in planning the attacks that killed 223 people, including American officials. Al-Libi was part of Osama bin Laden’s inner circle in the 1990s, was among the top remaining leaders of al-Qaeda, and his name was among the first placed on the FBI’s list of most wanted terrorists after the September 11 attacks.

After more than a decade of systematic hunting by the US for the terrorists linked to the bombings, the al-Qaeda operative was captured outside his home in Libya last month. US Special Operations Forces encircled and ambushed al-Libi’s vehicle and swiftly captured him from the streets of Trampoli, Libya. Special forces secretly removed him and transported him outside Libyan borders for safe detention under US custody. He was transferred to the USS San Antonio, a US Navy warship stationed somewhere in the Mediterranean at the time, where he was held for interrogation.

US officials anticipated a lengthy detention at sea for interrogation purposes; however, the suspect’s health took a turn for the worst, requiring speedy transport to the United States. Al-Libi’s wife informed the media that her husband was plagued with Hepatitis C and had been very sick. Al-Libi was transported to New York, where he was arrested and subsequently appeared before a judge. He is now at the mercy of the United States judicial system after a rare instance of U.S. military involvement in his secret removal from Libya, known as “rendition.”

Global dispute erupted in the media concerning whether the US could legally prosecute the accused under International law after forcing his capture and detention by rendition, rather than through extradition.

It is this involvement in rendition—the practice of grabbing a terrorism suspect to face trial without an extradition proceeding—that has fueled global debate as to whether U.S. custody of and exercise of jurisdiction over al-Libi is lawful under International Law. As a general rule, individual states exercising custody over an accused may litigate domestic proceedings against the individual. This principle assumes that a state has proper jurisdiction under International Law.

There are three basic categories of jurisdiction in International Law: 1) jurisdiction to prescribe, or prescriptive jurisdiction, confers the power to make laws; 2) jurisdiction to enforce enables a state to compel compliance with its law; and 3) jurisdiction to adjudicate allows a state to subject persons or things to the authority of its courts. To properly exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction over the accused, a state must have jurisdiction to prescribe against the offense committed, giving it grounds to compel its enforcement of the law against an individual, for example, through extradition, in order to bring the accused within the State’s borders, properly subjecting him to the State’s courts.

Global dispute erupted in the media concerning whether the US could legally prosecute al-Liby under International law after forcing his capture and detention by rendition, rather than through extradition. Extradition is the formal procedure recognized by treaty or agreement between States that dictates how an accused is transferred between those sovereign territories. The extradition process provides that a prosecuting State who has properly charged the accused may request that the host State—the State where the accused is located—relinquish custody and extradite the accused to the prosecuting State.

Extradition is a well-established international method for gaining custody and compelling enforcement of a State’s laws against an accused, beyond that State’s territorial borders. The rare practice of rendition carried out by the U.S. in capturing al-Libi has been met with criticism that such actions were illegal under International Law and, therefore, strip the United States of its jurisdiction to prosecute him.

It has been established internationally and is well settled within the United States that the legality of the method used in gaining custody remains separate from a State’s assertion of jurisdiction over the accused.

Recent trends in the international community show a general recognition of the ability of a state to abduct and capture a wanted criminal on foreign soil in order to bring the accused within its custody and carry out domestic prosecution against him. The legality of such practice under International Law, when carried out without the consent of the host State and without seeking extradition, has not been made clear. It has been established internationally, however, and is well settled within the United States that the legality of the method used in gaining custody remains separate from a State’s assertion of jurisdiction over the accused and the State’s ability to adjudicate once the accused is within its custody.

The practice of male captus bene detenus, which means drawing a distinction between means of apprehension and jurisdiction to prosecute, is not a novel concept in the International community. Legal precedent for this concept is manifested in the Israeli apprehension of Adolf Eichmann in Argentina, an ex-Nazi whose capture was pronounced lawful by a Jerusalem court in 1962. In 1998, General Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London on a warrant issued by a Spanish court for human rights violations committed in Chile. The capture of al-Libi in Tripoli, Libya, on a warrant issued by a New York federal court for involvement in bombings of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania befits this model of aggressive extraterritorial jurisdiction and enforcement.

The United States has reinforced this international phenomenon of exercising jurisdiction and enforcement, even in the absence of extradition. The common law countries, including Great Britain and the United States, historically viewed extradition as a duty under International Law. For the United States, the duty to extradite was – and remains – limited to situations in which a treaty exists between the two nations. Today, the United States is a party to at least one hundred bilateral extradition treaties. No such treaty exists, however, between Libya and the United States. U.S. officials, including Secretary of State John Kerry, suggested that any attempt to negotiate such a compromise would be unsuccessful and unwise due to the instability of the Libyan government and its potential inability to execute a cooperative transfer.

The ability of a State to assert adjudicatory jurisdiction in its domestic court may turn on whether the domestic law comports with international law.

The complicated questions concerning the legality of al-Libi’s capture under International Law are not likely to interfere with a subsequent criminal prosecution in the United States, due to the “Ker–Frisbee” doctrine—the US counterpart to the international concept of male captus bene detenus. Named after the pair of Supreme Court decisions from which it derives, Ker-Frisbee stands for the proposition that criminal defendants cannot seek to dismiss the charges against them on the ground that their presence was secured unlawfully. This doctrine was reaffirmed in a 1992 Supreme Court ruling in which the court held that despite the existence of a bilateral extradition treaty, the abduction of a foreign national does not prohibit him or her from standing trial in the United States.

Assuming arguendo, that the means of capture has no bearing on a State’s authority to prosecute an accused criminal once in custody, the ability of a State to assert adjudicatory jurisdiction in its domestic court turns on whether the domestic law comports with International Law. The U.S. Supreme Court emphasized this crucial intersection between domestic and international law in the seminal case of The Paquete Habana, in which the Court pronounced, “International law is part of our law, and must be ascertained and administered by the courts of justice of appropriate jurisdiction as often as questions of right depending upon it are duly presented for their determination.” Accordingly, United States courts must heed the dictates of International Law in matters of jurisdiction.

The international trend of expanding extraterritorial jurisdiction is in large part a result of the need to protect against extremist terrorist organizations by affording a mechanism to assert authority over these criminal organizations who are not identified with a particular State. The evolution of terrorist organizations in the last few decades has been acknowledged on an international level, gaining special attention at several conventions, and resulting in new legislation from the United Nations General Assembly. The “nomadic” nature of terrorist groups (pdf) make it impossible to identify them with any particular State and are held accountable as non-state actors. As a result, the traditional view that international law applies to nations and not to individuals “ignores the multi-state reality” of modern-day terrorism, allowing non-state actors to “take advantage of their status to paralyze the responses of authorities.”

The prosecutorial role of individual states and nation-states against terrorists is critical.

International efforts to aid the fight against terrorism have taken steps to hold individuals and organizations criminally liable for acts of terror. For example (pdf), the United Nations resolution of 1985, condemned as “criminal” all acts of international terrorism; the UN Crime Congress proposed antiterrorism jurisdiction for the International Court of Justice and later instituted an independent tribunal for certain crimes called the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC was the result of a treaty adopted during the “Rome Conference,” a UN conference. The prosecutorial role of individual states and nation-states against terrorists is critical, however, as the ICC acts only as a body of “last resort” and has a full plate.

The Rome Statute expresses intent to subordinate jurisdiction of the ICC to the national prosecution of criminal acts and will interfere if national authorities are unwilling or unable to carry out a genuine investigation and prosecution. The limited availability and resources of a designated international criminal tribunal to preside over all accused terrorists and all others accused of crimes against humanity and acts of war emphasizes the important role of State actors to prosecute terrorists when they have the authority and ability to do so. Accordingly, over time, the adjudicatory jurisdiction of state actors to prosecute criminals as recognized under customary international law, has steadily expanded to account for a broader array of categories of crimes and accused persons.

In order for the US Federal Court to properly establish that its prosecution of al-Libi, is proper under International law, its assertion of extraterritorial jurisdiction must be recognized under International law.

Setting aside the means of his capture, now that the US has custody of al-Liby, accused of committing acts of terror in violation of United States Criminal Law, its ability to prosecute turns on whether International Law recognizes the American court’s assertion of extraterritorial jurisdiction over the accused terrorist. Before an American court asserts extraterritorial jurisdiction, it must address two issues: 1) whether the United States has the power to reach the conduct in question under traditional principles of International Law; and 2) whether congress intended the statutes under which the defendant is charged to have extraterritorial effect.

The first prong of this test refers to the prescriptive jurisdiction of the State, or the authority of Congress to enact certain legislation under International Law. The second speaks to the ability to enforce a law after Congress has enacted a statute. If the court meets this two-prong test and its asserted jurisdiction is recognized under International Law, the court finally must determine whether exercising adjudicative jurisdiction would comport with due process.

In order for the U.S. Federal Court to properly establish that its prosecution of al-Libi is proper under International law, its assertion of extraterritorial jurisdiction must be recognized under International law. The first element in this test is to consider whether the United States has the power to reach the conduct in question under traditional principles of International Law. International Law recognizes five general bases upon which an American court could assert jurisdiction to prosecute extraterritorial terrorism:

- Territorial: Jurisdiction based upon the situs of the crime.

- Nationality: Jurisdiction based upon the nationality of the offender.

- Protective: Jurisdiction based upon the protection of significant national interests.

- Universal: Jurisdiction based on customary law or upon the prosecuting state’s physical custody of the offender.

- Passive personality: Jurisdiction based on the nationality of the victim.

Three of these bases for jurisdiction provide the appropriate recognition for the United States to reach the acts of terror committed outside US territorial boundaries against the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

A rarely used, but potentially valid source of conferred jurisdiction could be asserted under universal jurisdiction.

First, passive personality jurisdiction allows a State to assert jurisdiction over an individual who harmed, killed, or intended to harm or kill a National or Official of that State. The bombings committed in 1998 were aimed at U.S. Embassies located in Kenya and Tanzani, in order to maim and kill U.S. citizens and U.S. officials, along with African citizens and officials. At least twelve U.S. citizens and officials were killed in the bombings carried out with the aid of al-Liby, bringing him squarely within the passive personality jurisdiction of the US.

The second potential bases for jurisdiction is the authority of the US to assert protective jurisdiction based upon the protection of significant national interests. The nature of the attack aimed at US embassies placed national interests under threat and prompted the Government to defend those interests from further harm aimed at U.S. territory or Government entities abroad. The acts carried out by al-Libi were driven by the desire to gain political leverage and apply political pressure by harming the United States economy and system of government.

Finally, a rarely used, but potentially valid source of conferred jurisdiction could be asserted under universal jurisdiction. Unlike the other jurisdictional forms, aimed at the nationality of a person or territorial presence of perpetrator or acts committed, universal jurisdiction confers jurisdiction upon any state actor over the crime itself. Universal jurisdiction has customarily included specific crimes that are considered to be crimes against humanity, such as genocide, war crimes, and torture.

Under universal jurisdiction, any State has jurisdiction over a crime and accordingly the perpetrator of the crime who has been deemed by the international community as hostis humani generis—a common enemy of mankind. Doing so benefits the well-being and protection of all nations and interests of their citizens. Although the crime of terrorism has not been explicitly listed as a crime falling within this jurisdiction, the international trend has recognized it as such. For example, the United Nations Charter codified the crime of terror as an international crime. The nomadic nature of terrorist organizations and their access to dangerous chemical weapons and weapons of mass destruction have compounded the severity of modern day acts of terror.

Congress has left no room for interpretation and has abolished any doubt as to whether it intended for extraterritorial jurisdiction to apply to any person accused of committing an “act of terror.”

Once the United States Congress is afforded the power to enact legislation reaching acts occurring outside the bounds of its domestic territory, they must enact a statute and clearly intend that its authority was meant to have extraterritorial affect. Al-Libi was indicted in 2000, and faces criminal charges under 18 U.S.C. § 2331, including several statutes cross-referenced in that section relating to criminal “acts of terror.”

The statute provides specific details as to what qualifies as an act of terror. It includes any attempts, conspiracy, planning, or actual action taken to commit an “act of terror” intended to harm, maim, kill, or coerce any US citizen, official, property, or national interest. The statute specifically includes within the definition of “act of terror” the use of explosives, deadly weapons, or chemical weapons against Government building or property abroad, or against any Government official. Congress has left no room for interpretation and has abolished any doubt as to whether it intended for extraterritorial jurisdiction to apply to any person accused of committing an “act of terror” as defined in the statute.

The United States Court can properly exercise jurisdiction over al-Libi but is left to determine whether its jurisdiction to adjudicate the matter comports with due process.

Satisfying both prongs of the extraterritorial jurisdiction test as recognized under International law, the United States Court can properly exercise jurisdiction over al-Libi but is left to determine whether its jurisdiction to adjudicate the matter, or authority to subject persons to the process of its courts, would comport with due process. The general standard is that a violation of due process would occur if the exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction would be arbitrary or unfair.

Two approaches to this standard have developed among the Federal Courts: 1) the international law approach and 2) the “nexus approach.” The first approach, followed by the First, Third, and Eleventh Circuits, states that jurisdiction is consistent with due process if it is proper under International Law. This test is easy to apply: a court must determine whether extra-territorial jurisdiction is proper under International law before they assert such jurisdiction over an accused individual. If the two prong-test explained above is met, due process is automatically proper.

The Second Circuit, encompassing New York Federal Courts, where al-Libi is being tried, follows the second approach, along with the Ninth Circuit. This “nexus approach” states that due process is consistent if there is a sufficient “nexus” between the defendant and the United States such that the jurisdiction is not “arbitrary or fundamentally unfair.”

The Second Circuit took this approach in United States v. Yousef, in which the defendant conspired to place bombs on twelve American commercial airplanes. In a test run, he placed a bomb on a Philippine Airline flight traveling to Japan, killing a Japanese citizen. The defendant claimed the district court’s exercise of jurisdiction over him violated due process because no American citizens or property were harmed. The Second Circuit held due process was consistent with the exercise of jurisdiction because the injury occurred during a test run in furtherance of the conspiracy to attack American airplanes; the nexus was satisfied by “the substantial intended effect of their attack on the United States and its citizens.” According to the standard applied by this circuit in Yousef, Al-Libi’s role in planning and effectuating the attack on American Embassies, causing the deaths of several American Government Officials tends show a nexus between the intended effect on American citizens and al-Libi’s actions.

Despite the complex obstacles posed by the intersection of Domestic and International Law, the US has continued to move forward in its efforts to expand jurisdiction over international terrorists in its fight against the war on terror. The international community likewise has turned a cheek and in several instances followed suit in the aggressive approach to take control of certain criminals in order to prosecute them under domestic law. The United States courts appear to be an emerging weapon to deter terrorist organizations evading punishment and consequences for the grave acts of terror committed around the world. A reporter for Amnesty International suggested that this international trend of allowing the ends to justify the means—permitting jurisdiction once an accused is in custody regardless of the manner of capture—suggested it was a key part of the United States Government’s modus operandi in the war against al-Qaeda.

Kaitlin Rothecker is a 2L student at Campbell Law School. Kaitlin may be reached via email at knrothecker1113@email.campbell.edu.