Unlock the source of your greatness…at a dangerous cost

The privacy policies of popular ancestry-tracing companies have come into question following research into how participants’ DNA information may be unknowingly stored and shared with third parties.

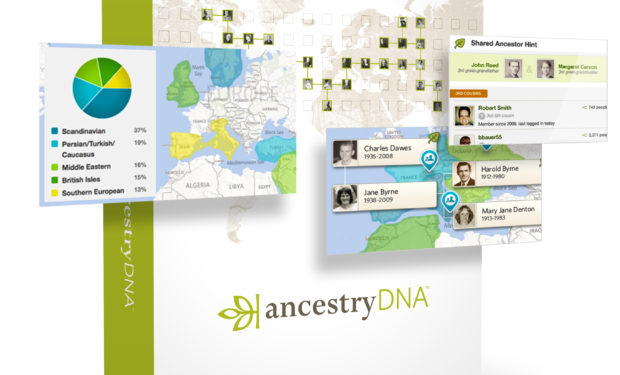

“AncestryDNA can reveal the source of your greatness”—but at what cost? In an attempt to allure future customers, sites like Ancestry.com promise to help consumers explore their genetic makeup and find out what makes them unique. While promising a service that is both simple and convenient, a critical analysis of the privacy policies reveal that things are not nearly as straightforward as they seem. In fact, the more widespread these services become, the more serious the consequences could be for society as a whole.

These at–home test kits, marketed by direct–to–consumer (DTC) genetic testing companies, have experienced a drastic increase in popularity in recent months. Though the brands may differ, they each follow a similar simple process—users need only spit into a tube or swab the inside of their cheeks before returning their sample to the lab in the pre–paid envelope included within the kit.

Weeks later, after the results have been released, users are able to learn about their own unique genetic history, uncovering things such as who their ancestors were, what their health risks are, and whether they could be a “carrier” for specific genetic conditions. The methods employed by these companies are convenient, simple to follow, and easy to understand; however, the privacy policies currently in place, while perhaps not nefarious in fact, are at best confusing, verbose, and lacking in clarity. This has led to mounting concern that the average consumer, who has been trained to simply “click to accept” rather than actually read through terms and conditions, may not actually understand the risk of what they are agreeing to give away.

Companies responsible for creating these at–home genetic tests, such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe, collect two types of data from each user. First, they collect personal information from the user at the time that person creates an account on the website and sets up a personal profile. This operates in a manner similar to that of any other social media site, in that the individual user is able to choose what, and how much, information they would like to share with other site users.

Second, the companies collect genetic information, which is obtained through the biological sample shared with the company by the user. This includes the full sequence of that person’s DNA—something uniquely identifying to each individual person.

These processes of collecting data have led to privacy concerns, especially regarding the ownership rights of the samples. By participating in one of the at–home genetic tests, a user is not granting the ownership rights of their DNA to the company. Rather, a licensing agreement is created in which the company is permitted to use and store the supplied genetic material for the specific purpose granted by the user.

Genetic data, such as DNA, is unique to the individual and cannot ever be completely “de–identified.”

Although this permission may be withdrawn at the request of the user at any time and for any reason, the means of actually revoking consent may not be so simple or straightforward in practice. Furthermore, the mere act of granting a license to these companies to use one’s DNA data, even if for a seemingly limited purpose, does give them significant rights over data that is incredibly personal and can create certain privacy risks that may not be immediately apparent.

Before granting a license for a company to use and process genetic data, it is important that potential users understand exactly what these licenses entail. Part of the processing procedure, for example, requires the companies to send the genetic sample to third–party laboratories. Although “de–identified”—meaning the sample has been stripped of the owner’s name and other shared personal information—it is important to note that genetic data, such as DNA, is unique to the individual and cannot ever be completely “de–identified.” Furthermore, typical privacy policies within this industry require users to consent to sharing their “anonymized” data for aggregate research, as well as with partner companies, facts which may not be obvious absent a thorough reading of the privacy policy.

By clicking “continue” to create an account, users consent to let the companies collect, use, and share their personal and genetic data.

Although there are several different companies actively promoting their own versions of at–home genetic tests, the privacy statements of each are essentially the same. The statement used by Ancestry.com, for example, is illustrative of the policies typically used within the DTC genetic testing industry. By clicking “continue” to create an account, users consent to let the companies collect, use, and share their personal and genetic data.

Users are also required to consent to having their genetic sample sent to a third–party laboratory for processing. Their DNA is then converted to a digital code which is used to provide unique information, such as ethnic background and potential health risks, to the user. This data is protected unless the user consents, on a separate form, to participate in research projects conducted by undisclosed third–parties; however, related brands and partner companies may be able to access user data, by virtue of the original consent release. Privacy settings can be managed by visiting these additional sites, a fact likely unnoted by the majority of participants.

The companies promise that users may delete their data, information, or account at any time, notwithstanding the fact that the actual process of permanently deleting information is rather complicated. Personal information may be deleted by the user, although sites like Ancestry.com continue to hold these records within their archives. Successfully removing information from the archives may be a feat in and of itself, as users are required to contact the archival entity responsible for maintaining these records, and removal requests will only be considered on a case–by–case basis.

Genetic information can be deleted by request and is typically done within 30 days. To destroy the original biological sample, however, the user must also contact the related department within the company and submit a request. Even after everything has been deleted, the personal and genetic data will persist within the company’s backup system for up to six months, until it is overwritten.

For users that agree to participate in outside research projects, separate consent forms must be signed. It is noteworthy that these projects may continue for years, and an individual’s data may not be deleted from the project while it is taking place. This means that, even if the user wishes to delete their personal and genetic information from the main site, that information will not be deleted from the research site if it has been involved in a past, or current, project. It will, however, not be used in future research once a request for removal has been successfully processed.

Without proper protections in place, these inexpensive testing kits could ultimately cost consumers far more than what they have bargained for.

The Federal Trade Commission has issued a warning to users of these products, informing them of potential risks and privacy hacks, cautioning them to carefully read the privacy statements before giving up their personal information. Although the genetic testing companies themselves promise to use reasonable efforts to safeguard customers’ information from being hacked, there is no real way for customers to know about the security of the third–party companies that may be involved.

There are other potential issues as well. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) does not protect information processed by companies like 23andMe or Ancestry.com. Even though genetic information has been classified as health information by HIPAA, the DTC genetic testing companies that create the test kits are not considered to be healthcare providers. Therefore, they are not governed by the regulations set forth within HIPAA, and the information they process is not protected by that law. These companies would be permitted to sell user data to pharmaceutical companies, for example. Even if the data is anonymized, it is still possible to positively identify individuals by using publicly available research databases.

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) passed in 2009, serves to protect employees and job applicants from discrimination based on their genetic information, such as that revealed by family medical history or medical tests. This law has real limits, however, as well as loopholes that may be exploited. The law applies to most employers and health insurance companies, but it does not cover schools, life insurance companies, long–term care, or disability insurance carriers. Thus, these supposedly innocuous genetic tests have the potential to lead to very serious unanticipated consequences as people may be denied certain services based on the fact that they happen to carry a particular gene.

At–home genetic tests continue to rise in popularity and are likely not going anywhere soon. Despite the fact that DTC genetic testing companies do lay out their policies in consent forms, the forms are lengthy, complicated, and often not contained all on the same webpage. Consumers, curious about who they are and where they come from, are all too eager to simply accept the terms and conditions presented without actually reading or understanding just what they are giving away. Without proper protections in place, these inexpensive testing kits could ultimately cost consumers far more than what they have bargained for.