Blanket drug testing of college students declared unconstitutional

The Eighth Circuit held that a college’s mandatory drug testing policy constitutes an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment.

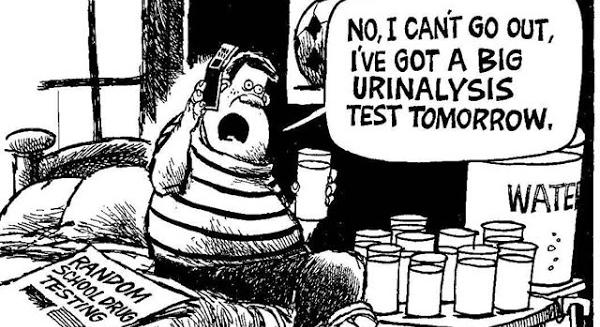

During the first week of classes, the typical college student’s back-to-school to do list consists of buying school supplies, getting textbooks, and preparing for class. But for students at Linn State Technical College, there was one more item on the agenda: submit a urine sample for drug testing. Prior to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit’s decision in Kittle-Aikeley v. Strong, all incoming students at Linn State were required to submit to mandatory drug-testing. Following a class action by students of the college, Linn State’s mandatory drug-testing policy has been declared unconstitutional. Specifically, the Eighth Circuit held that the policy violated the students’ Fourth Amendment rights.

Linn State is a two-year, publicly funded technical college in Linn, Missouri. The program at issue, adopted by the Board of Regents in 2011, requires mandatory drug testing of all incoming degree- or certificate-seeking students. Students are required to submit a urine sample within ten days of the start of the semester and the sample is tested for eleven drugs. If the test comes back positive for drugs, the student is placed on probation and must complete a drug-awareness course or counseling, submit a second urine sample within forty-five days, and will be subject to a third drug test to be administered randomly. If either of the subsequent tests return positive, the student will either be required to withdraw or will be administratively withdrawn from the school. Refusal to submit to the drug test will result in automatic withdrawal, unless the President, in his discretion, waives the requirement for reasons such as unique health and safety issues or moral, philosophical, or religious objections.

After submitting to the college’s mandatory drug testing policy, Branden Kittle-Aikeley and other members of the Linn State chapter of Students for Sensible Drug Policy in coordination with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), filed a class-action constitutional complaint against President Donald Claycomb and members of Linn State’s Board of Regents, seeking injunctive relief. On November 18, 2011, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Missouri granted a preliminary injunction, prohibiting Linn State from further collecting or testing urine samples. On July 1, 2013, the district court conducted a bench trial and upheld the mandatory drug testing policy as it applies to students enrolled in programs that the court determined to be safety-sensitive (i.e. aviation maintenance, electrical distribution systems, industrial electricity, power sports, and CAT dealer service technician programs). This order permanently enjoined Linn State from drug testing students who enrolled in programs that do not pose significant safety risks to others. After an appeal by Linn State that resulted in a reversal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit granted the Student’s petition for rehearing, vacating their previous panel decision and reviewing the case en banc (before the entire bench).

The plaintiffs in this case argue that since the drug tests are a blanket requirement and are not based on any suspicion of actual drug use, they amount to unreasonable searches under the Fourth Amendment.

The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution guarantees “[t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” In Chandler v. Miller, the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit held that collecting urine samples for drug testing is a search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. The plaintiffs in this case argue that since the drug tests are a blanket requirement and are not based on any suspicion of actual drug use, they amount to unreasonable searches under the Fourth Amendment.

The Fourth Amendment generally prohibits searches without probable cause, but in Griffin v. Wisconsin, the Supreme Court of the United States has recognized exceptions to this general rule “in certain well-defined circumstances, including those in which the government has special needs, beyond the normal need for law enforcement.” Whether or not the government has special needs is a preliminary question of fact to be determined by the court. Once the special needs requirement has been satisfied, the court must conduct a balancing test between individual privacy expectations and government interests “to determine whether it is impractical to require a warrant or some level of individualized suspicion in the particular context.”

[T]he Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the District Court’s order, permanently enjoining Linn State from drug testing students “who were not, are not, or will not be enrolled in safety-sensitive programs.”

Linn State, as a technical college offering practical, hands-on programs, attempts to demonstrate special needs by proffering four policy goals: “to maintain a safe, secure, drug-free and crime-free school; to deter and prevent student drug use and abuse; to identify students who need assistance; and to promote student health.” Of these four interests, the court accepted only one: the need to maintain safety, as indicative of a special need justifying departure from the usual warrant and probable cause requirements. The court based this finding on the rationale of the Supreme Court in Skinner v. Railway Executive’s Association and National Treasury Union v. Von Raab, which allow for “suspicion-less drug testing of individuals employed in safety-sensitive occupations.”

After determining the existence of a special need, the court applied the exception to Linn State in the same way that the District Court did, through a program-by-program analysis. Linn State offers 28 different programs that are divided into six categories: arts and sciences, civil technology, computer technology, health sciences, industrial technology, and transportation technology. Within these categories are safety-sensitive programs, such as aviation maintenance and heavy equipment operations, as well as programs that are not safety-sensitive, such as design drafting. Noting this distinction, the court concluded that “by requiring all incoming students to be drug tested, Linn State defined the category of students to be tested more broadly than was necessary to meet the valid special need of deterring drug use among students enrolled in safety-sensitive programs.” Thus, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the District Court’s order, permanently enjoining Linn State from drug testing students “who were not, are not, or will not be enrolled in safety-sensitive programs.”

The court’s opinion presents lessons that can be taken away by colleges and student activists alike.

As Vernonia School District v. Acton and Board of Education of Independent School District No. 92 of Pottawatomie County v. Earls demonstrate, application of the Kittle-Aikeley decision is limited in scope to colleges. These Supreme Court cases upheld suspicion-less drug testing of students participating in athletics and other competitive extra-curricular programs at high schools and middle schools. The critical difference being that unlike college students, middle and high school students are “children who had been committed to the temporary custody of the State as schoolmaster” and the State has “undertaken a special responsibility of care and direction.” Colleges and universities, however, do not step in to a custodial role with their adult students, so this type of justification does not apply.

The court’s opinion presents lessons that can be taken away by colleges and student activists alike. In order to survive a Fourth Amendment challenge, colleges with similar policies must show special needs such as the one shown here for safety concerns. Other special needs could be demonstrated by a campus drug use crisis greater than that experienced by other colleges, which Linn State failed to establish. Blanket suspicionless drug testing policies will not be upheld solely on the basis that they promote healthy and productive work environments. Additionally, any policy that requires drug testing of all students is very unlikely to survive a Fourth Amendment challenge. With chapters in nearly every state, the Students for Sensible Drug Policy Organization, along with the ACLU, stands ready to assist students in fighting constitutionally unreasonable drug testing programs.