Gay Rights v. Religious Rights: Can public officials deny marriage licenses to gay couples?

Some magistrates argue they should not be required to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples because doing so would interfere with their religious beliefs.

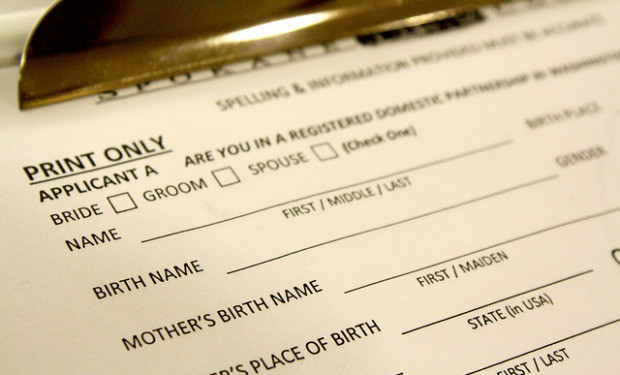

It is almost impossible to look at a news source without seeing a story about the newest victory in the gay rights movement. States across the country are lifting the ban on gay marriage, even traditionally conservative states like Kansas, Alaska, and Idaho. As of now, thirty-five states have legalized same-sex marriage, while fifteen states still ban the practice. A recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court to deny review of pending appeals to overturn the repeal of gay marriage bans has given the gay rights movement incredible momentum. A new question has arisen in the wake of legalization: can clerks or magistrates deny marriage licenses to gay couples based on their religious convictions?

“North Carolina magistrates have been directed to perform civil marriages for same-sex couples or face suspension or dismissal from their state jobs…”

One result of the Supreme Court’s decision was the legalization of same sex marriage in North Carolina, based on a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit which overturned the gay marriage ban in Virginia. Absent the Supreme Court’s intervention, the Fourth Circuit’s decision remains controlling federal authority in North Carolina. Gay marriage officially became a reality in North Carolina on October 10, 2014. The first reported case of discrimination arose only three days later.

On October 13, 2014, a Pasquotank County magistrate denied a marriage license to a same-sex couple, Randall Jackson and William Locklear. Jackson and Locklear, partners of thirty-one years, attempted to apply for a marriage license at the courthouse in Elizabeth City. State magistrate Gary Littleton refused to marry the couple, citing his religious belief that marriage should only be between a man and a woman. The State of North Carolina quickly responded with a memorandum issued by the Administrative Office of the Courts. An accompanying statement was released on October 16, 2014, reading “North Carolina magistrates have been directed to perform civil marriages for same-sex couples or face suspension or dismissal from their state jobs. A memo to state magistrates Wednesday said they would be violating their oaths of office if they refuse to marry gay or lesbian couples.”

Since the memorandum and statement were released, magistrates across North Carolina have resigned due to their religious beliefs against gay marriage. Director John W. Smith of the Administrative Office of the Courts wrote a letter stating his concerns after the resignations began:

“I want to assure you and all of the people of our state that I respect our magistrates who hold sincere and deep religious beliefs that have placed them in conflict with the duties of their appointed judicial office. Those who have resigned demonstrated their thoughtful choices in resolving their moral dilemmas. At the same time, other magistrates with equally sincere and deep religious beliefs recognize a quite clear distinction between marriage as a civil ceremony conferring legal status, and marriage as a religious institution quite apart from temporal concerns.”

Magistrates and clerks are state employees that take two oaths in which they promise to uphold the Constitution of the United States and to faithfully and impartially perform their duties.

This ongoing situation has sparked the debate over whether magistrates (and other civil servants) can refuse to perform marriages for gay couples.

Clerks are officers of the court who file papers, issue process, keep records, issue marriage licenses, and in some states perform marriage ceremonies. Magistrates operate as quasi-judicial officers of the court with the power to administer the law and are tasked with duties including setting bail, dealing with minor offenses, issuing warrants, and in North Carolina, performing marriage ceremonies. In other states, civil servants are appointed to perform marriages outside of an ordained minister. Magistrates and clerks are state employees that take two oaths in which they promise to uphold the Constitution of the United States and to faithfully and impartially perform their duties. What happens when the public official has religious beliefs that contradict with his or her duty as an officer of the court? Can a public official deny a marriage license to a gay couple or refuse to marry a gay couple?

There are three possible rights that a magistrate/clerk could assert in order to refuse performing gay marriages: (1) a free exercise right under the First Amendment, (2) a statutory right under a state Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), and (3) a statutory right under Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Free Exercise Claim

In the United States, the First Amendment states that Congress shall make no law “prohibiting the free exercise” of religion. This Amendment has since been interpreted to mean that the government cannot compel affirmation of a conflicting belief, “penalize or discriminate against religious individuals or groups because they hold religious views abhorrent to the government,” nor “employ the taxing power to inhibit the dissemination of particular religious views.” However, the Supreme Court has rejected the idea that religious beliefs are completely free from restrictions. The Court set up a test to analyze whether an individual has a free exercise claim: the law cannot significantly burden a sincerely-held religious belief or exercise of religion by an individual. If the law does burden a religious belief, it must either be generally-applicable and neutral or, if discriminatory, the law must further a state’s compelling interest and be the least restrictive means to achieve that interest.

Under this analysis, the magistrates have a valid free exercise claim because the state law requiring the performance of gay marriages can be viewed as placing a significant burden on the magistrates and clerks who are legally required to perform the marriages even though it is against their religious beliefs to do so. On this side of the debate, the argument is that the government does not have a compelling interest through least restrictive means to force religious clerks and magistrates to perform gay marriages.

However, Justice Scalia writes “the right of free exercise does not relieve an individual of the obligation to comply with a valid and neutral law of general applicability.” Thus the prevailing argument is that gay marriage laws are neutral and generally applicable because the laws are not intended to burden religious practices. Arguments on this side of the debate made a distinction between magistrates performing civil ceremonies and ministers performing religious ceremonies. Additionally, the state has a compelling interest in maintaining a non-discriminatory government and the law requiring gay marriage is the least restrictive means that the state could employ to carry out this interest.

RFRA Claim

In response to the decision in Employment Division v. Smith, which effectively eliminated the compelling interest test under the Free Exercise Clause for neutral and generally-applicable laws, Congress passed legislation that restored this test to “all cases where free exercise of religion is substantially burdened.” Thus the federal RFRA states that the “[g]overnment shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability” unless the government has a compelling interest and uses the least restrictive means to further that compelling interest.

However, the federal RFRA only applies to the federal government. A state would have to adopt its own version of the RFRA in order for its provisions to apply to state actions. There are only thirteen states with a state RFRA. North Carolina is still not among those states, though the state legislature tried, but failed, to pass a NC RFRA in 2013. Magistrates in other states may have a RFRA claim, but North Carolina magistrates will not.

Title VII Claim

Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it is unlawful to practice employment discrimination based on religious grounds. Any employee that is legally protected under this statute is entitled to a reasonable accommodation of the employee’s religious beliefs, so long as the accommodation does not place an undue hardship on the employer.

The issue surrounding this claim revolves around the question of whether a state magistrate, clerk, or appointed civil servant qualifies as an “employee” under the statute’s definition. According to Title VII, an employee is defined as any “individual employed by an employer.” The statute lays out several exceptions to this definition, including “an appointee on the policy making level.” A magistrate could fall under this exception, but clerks and civil servants would not fit under this argument because they do not have the discretion of “policy making,” and would therefore have a stronger argument under a Title VII claim. Additionally, even if a magistrate does not fit within the exception, there is an argument that magistrates should not be considered in making accommodations for their religious beliefs because of the nature of their duties, much like police officers (which court decisions have excluded from Title VII protection).